Landschlacht, Switzerland, Tuesday 17 September 2019

Damn that man!

One man’s writings has had and continue to have a major effect on my life and this has been reflected in my travels and I have already spoken of the man previously in this blog.

Above: Charles Dickens, New York, 1867

(Please see Canada Slim and the Dickensian Moment – first published as “Goodbye, Charles” on 9 June 2015.)

(As one of the shortest and woefully inadequate posts I have ever written, expect to see an updated version of “Goodbye, Charles” as soon as possible and the addition of another post that continues the chronicle of my first travels in Europe last described in Canada Slim and the Promised Land – first published as “That which survives 3: The promised land“.)

It was he who made me decide to first enter Britain via Broadstairs.

Above: Dickens House Museum, Broadstairs

It was he who compelled me to convince my good friends Samantha and Iain to visit his birthplace in Portsmouth.

Above: Charles Dickens Birthplace Museum, Portsmouth

It was he who inspired me to first find the courage to write.

It was he whose footsteps I was determined to trace during my visit to London in the last week of October 2017.

My wife had purchased for us two London Passes, offering free entry to over 60 attractions, as well as free public transport on buses, on the Tube, and on trains.

She strongly suggested I use mine as much as possible during the time when she was attending her medical conference.

26 October was the first day that I would have a chance to view London on my own.

I had, following the Passbook alphabetically, already visited the BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Manhir that morning, so my next goal was the Charles Dickens Museum in the Bloomsbury district.

Above: BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir

(For previous posts on London, please see….

Canada Slim….

- and the Paddington Arrival

- and the Street Walked Too Often

- Underground

- and the Outcast

- and the Wonders on the Wall

- and the Calculated Cathedral

- and the Right Man

- and the Queen’s Horsemen

- and the Royal Peculiar

- and the Lamp Ladies

- and the Uncertainty Principle

- and the Museum of Many

- and the Breviary of Bartholew

- and the Body Snatchers

- and the Freudian Slippers

- and the Mandir of Nose Hill )

London, England, 26 October 2017

Few cities are as closely associated with one writer as London is with Charles Dickens (1812 – 1870).

The recurrent motifs in his novels have become the clichés of Victorian London (though Dickens was active and successful before Queen Victoria came to the throne) – the fog, the slums and alleys, the prisons and workhouses and the stinking river.

Drawing on his own personal experience, Dickens was able to describe the workings of the law and the conditions of the poor with an unrivalled accuracy.

Above: Charles Dickens, 1850

Born in Portsmouth (Please see Canada Slim and the Dickensian Moment.), Dickens was the second of eight children.

His father, John Dickens, was a clerk who worked for the Navy and had set up home in Portsmouth with his wife Elizabeth.

Above: Old Portsmouth

In 1817 John was posted to the dockyard in Chatham.

John and his family took a full part in the life of the community.

They were friendly with neighbours and with the family of a local landlord.

Charles and his sister Fanny were frequently set up by their father atop a table in the Mitre Inn to entertain the tavern with songs and ballads of the day.

It was in Chatham that Charles began his education.

Above: Chatham Dockyard

His widowed aunt Mary Allen married for a second time while the Dickens family were in Chatham.

Above: 2 Ordnance Terrace, Chatham (Dickens’ home: 1817 – 1821)

This was to a widowed doctor, Matthew Lambert, who had a son Matthew, a little older than Charles and became a great influence upon this early part of Charles’ life, for it was Matthew who introduced Charles to the wonders of the theatre.

This was the beginning of a lifelong passion.

“I tried to recollect whether I had ever been in any theatre in my life from which I had not brought away some pleasant association, however poor the theatre, and I protest, I could not remember even one.”

In fact, Charles always had a great relish for bad theatre.

“Allow me to introduce myself—first negatively.

No landlord is my friend and brother.

No chambermaid loves me.

No waiter worships me.

No boots admires and envies me.

No round of beef or tongue or ham is expressly cooked for me.

No pigeon pie is especially made for me.

No hotel advertisement is personally addressed to me.

No hotel room tapestried with great coats and railway wrappers is set apart for me.

No house of public entertainment in the United Kingdom greatly cares for my opinion of its brandy or sherry.

When I go upon my journeys, I am not usually rated at a low figure in the bill.

When I come home from my journeys, I never get any commission.

I know nothing about prices, and should have no idea, if I were put to it, how to wheedle a man into ordering something he doesn’t want.

As a town traveller, I am never to be seen driving a vehicle externally like a young and volatile pianoforte van, and internally like an oven in which a number of flat boxes are baking in layers.

As a country traveller, I am rarely to be found in a gig, and am never to be encountered by a pleasure train, waiting on the platform of a branch station, quite a Druid in the midst of a light Stonehenge of samples.

And yet—proceeding now, to introduce myself positively—I am both a town traveller and a country traveller, and am always on the road.

Figuratively speaking, I travel for the great house of Human Interest Brothers, and have rather a large connection in the fancy goods way.

Literally speaking, I am always wandering here and there from my rooms in Covent Garden, London—now about the city streets: now, about the country by-roads—seeing many little things, and some great things, which, because they interest me, I think may interest others.

These are my chief credentials as the Uncommercial Traveller.”

In The Uncommercial Traveller, he revisited Rochester where he enjoyed the somewhat shaky productions he saw there.

He does not spare the company:

“Many wondrous secrets of Nature had I come to the knowledge of in that sanctuary:

Of which not the least terrific were, that the witches in Macbeth bore an awful resemblance to the Thanes and other proper inhabitants of Scotland, and that the good King Duncan could not rest in his grave, but was constantly coming out of it and calling himself somebody else.”

Above: High Street, Rochester

John Dickens’ job entitled him and his family to regard themselves as middle class, but the middle classes had little money behind them if things went wrong or if they couldn’t support their large families in seizing the opportunities they had anticipated.

Prosperity could unravel very quickly.

By the time John was recalled to London in 1822, the debts were considerable and his new post meant a drop in salary.

Above: John Dickens (1785 – 1851)

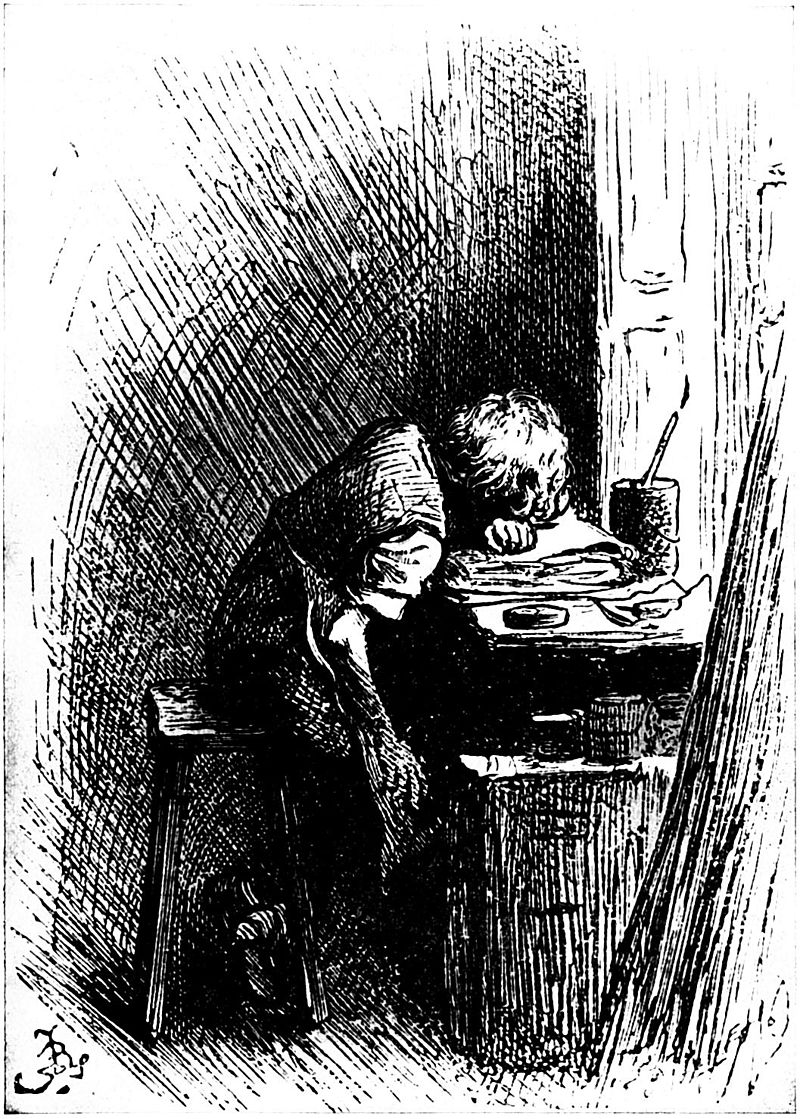

Such was the family situation in 1823 that the young Charles, age 11, had to go out to work, finding employment in a boot-blacking factory, Warren’s Blacking Warehouse, on the north bank of the Thames, near the site of the modern Charing Cross Station.

Charles and his colleagues had to cover pots of boot polish (blacking) and paste on to them paper labels.

He was paid six shillings a week.

Great numbers of children in early 19th century England would have done similar work – and many, much, much worse.

“It was a crazy, tumbledown old house, abutting, of course, on the river, and literally overrun with rats.

Its wainscotted rooms and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old grey rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and the decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again.

The counting house was on the first floor, looking over the coal barges and the river.

There was a recess in it, in which I was to sit and work.”

This episode affected Charles profoundly.

He thought his parents had given up on him.

“It is amazing to me how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age.

It is amazing to me, that, even after my descent into the poor little drudge I had been since we came to London, no one had compassion enough for me … to suggest that something might have been spared, as certainly it might have been, to place me at any common school ….

No one made any sign.

My father and mother were quite satisfied.

They could hardly have been more so, if I had been 20 years of age, distinguished at a Grammar School and going to Cambridge.”

Above: Cambridge University coat-of-arms

On 20 February 1824 John Dickens was arrested and imprisoned in Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison.

Above: Marshalsea Prison Gate

Charles was deeply ashamed of his family’s circumstances and hurt further when his mother forced him to keep his blacking job even after his father’s release.

Above: Elizabeth Dickens (1789 – 1863)

This influenced Dickens’s view that a father should rule the family, and a mother find her proper sphere inside the home:

“I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back.”

His mother’s requesting his return was a factor in his dissatisfied attitude towards women.

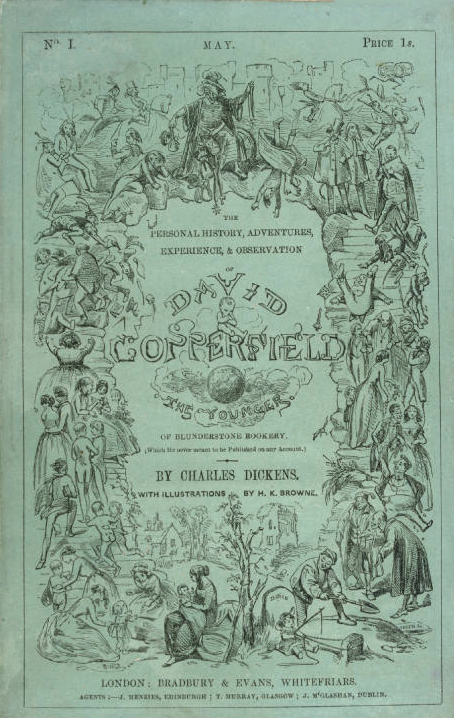

Righteous indignation stemming from his own situation and the conditions under which working-class people lived became major themes of his works, and it was this unhappy period in his youth to which he alluded in his favourite, and most autobiographical, novel, David Copperfield:

“I had no advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no assistance, no support, of any kind, from anyone, that I can call to mind, as I hope to go to Heaven!“

In the end, a number of circumstances brought an opportunity for change.

John inherited some money, began receiving a pension from the Navy and started working as a journalist, thus enabling the family to dispense with the few shillings Charles was adding to the family income.

Dickens got to school eventually.

He spent two years at Wellington House, which he remembered with little affection.

He did not consider it to be a good school:

“Much of the haphazard, desultory teaching, poor discipline punctuated by the headmaster’s sadistic brutality, the seedy ushers and general run-down atmosphere, are embodied in Mr Creakle’s Establishment in David Copperfield.”

When he left, at age 15, he was ready for work.

An acquaintance of the family found Charles work as a lawyer’s clerk with the firm of Ellis and Blackmore, which lasted 18 months.

Dickens worked at the law office of Ellis and Blackmore, attorneys, of Holborn Court, Gray’s Inn, as a junior clerk from May 1827 to November 1828.

Above: Gray’s Inn Square, London

Charles was a gifted mimic and impersonated those around him: clients, lawyers, and clerks.

He went to theatres obsessively—he claimed that for at least three years he went to the theatre every single day.

His favourite actor was Charles Mathews and Dickens learnt his monopolylogues (farces in which Mathews played every character) by heart.

Above: Charles Matthews (1776 – 1835)

Then, having learned Gurney’s system of shorthand in his spare time, he left to become a freelance reporter.

Above: Example of Thomas Gurney (1705 – 1770) shorthand

A distant relative, Thomas Charlton, was a freelance reporter at Doctors’ Commons and Dickens was able to share his box there to report the legal proceedings for nearly four years.

Above: Doctors’ Commons in the early 19th century

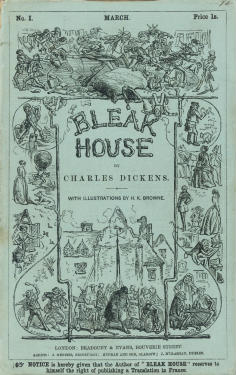

This education was to inform works such as Nicholas Nickleby, Dombey and Son, and especially Bleak House—whose vivid portrayal of the machinations and bureaucracy of the legal system did much to enlighten the general public and served as a vehicle for dissemination of Dickens’s own views regarding, particularly, the heavy burden on the poor who were forced by circumstances to “go to law“.

Charles had family in journalism.

His father wrote occasional pieces, but Charles also had a maternal uncle, John Henry Barrow, who in 1828 launched The Mirror of Parliament.

It was not long before Charles was part of Barrow’s parliamentary reporting team and was soon striking out writing for other publications, including the radical newspaper The True Sun.

Sometime before 1830, Dickens fell in love with a young woman called Maria Beadnell, the daughter of a banker.

The relationship between them flashed on and off for around four years, despite hostility from her parents, interference from friends and Maria’s own capricious nature.

The letters that survive show how thoroughly Dickens was absorbed in pursuing her.

Maria’s parents disapproved of the courtship and ended the relationship by sending her to school in Paris.

When the end finally came, he wrote to her, claiming:

“I have never loved and I can never love any human creature breathing but yourself.”

Above: Maria Beadnell (1810 – 1886)

She is thought to be the model for the character Dora in David Copperfield.

Above: David Copperfield and Dora Spenlow

Many years later, Dickens got a letter from Maria out of the blue and a short correspondence between them began in which he proclaimed the intensity of his original feelings for her.

The tone of these letters soon changed after he arranged to see her and she turned out to be “toothless, fat, old and ugly” (her words).

Above: Miriam Margoyles as Maria Beadnell Winter

The Maria romance is interesting because of the marked contrast it makes with Dickens’ engagement and marriage.

Catherine Hogarth, the daughter of his boss at the Evening Chronicle, could hardly have been a more different young woman.

At least Dickens looked at her in a completely different way.

His letters to her are affectionate but occasionally overbearing, as if he was asserting himself to ensure that no more nonsense got in the way of his own ambition.

He was particularly careful to outline the primacy of his work and its demands.

His commitments at this time were extremely heavy.

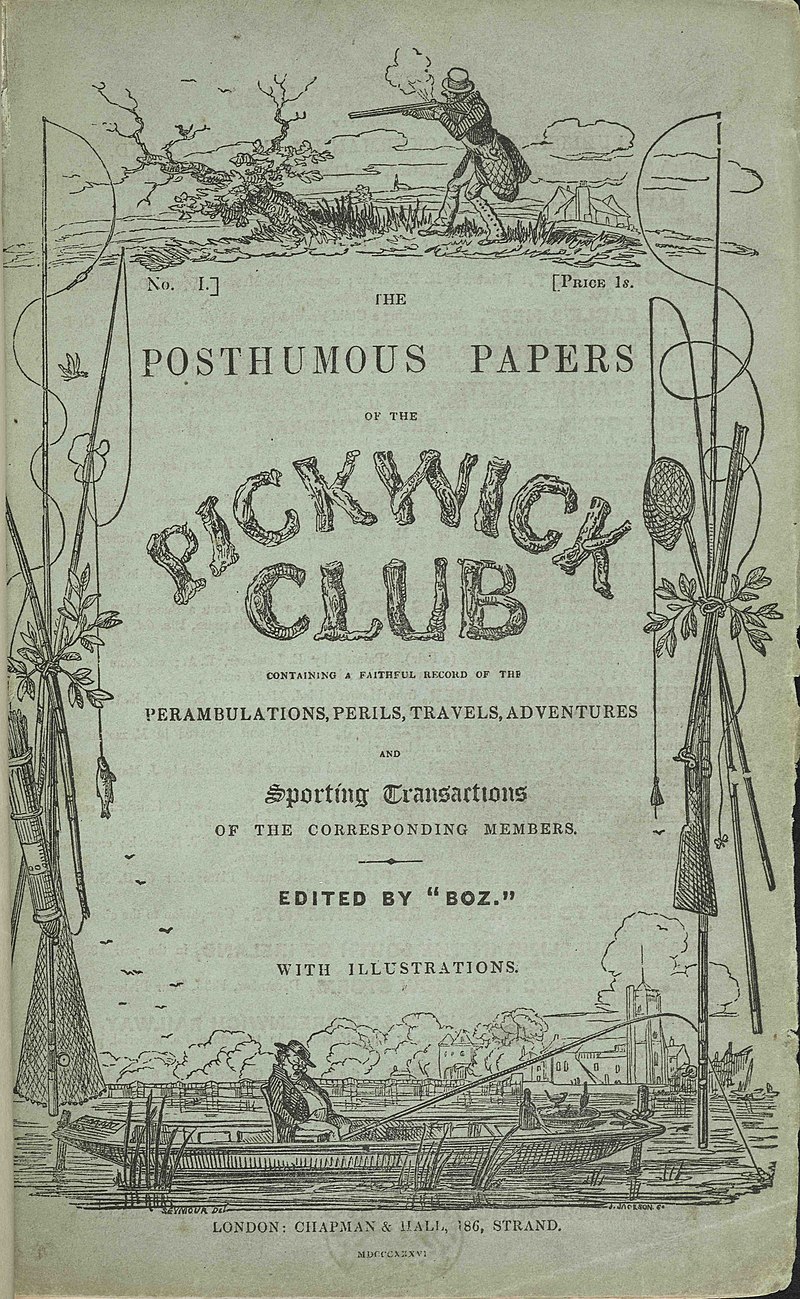

Catherine and Charles married on 2 April 1836 and went for a week’s honeymoon to Chalk in Kent (during which, true to form, Dickens was busy with The Pickwick Papers).

Above: Catherine Hogarth Dickens (1816 – 1879)

In August 1834 Charles was given a permanent position on The Morning Chronicle, a liberal paper, to report on all parliamentary matters.

This included elections (there were two in 1835) and political meetings – all around the country, before there were railroads.

Deadlines were nevertheless overwhelmingly important and Dickens experienced many freezing, wet stagecoach journeys, bouncing about, writing on his knees, racing back to London to get his account in before the rival reporters on The Times.

Dickens’ first published piece of creative work appeared in the Monthly Magazine in 1833.

It was called “A Dinner at Poplar Walk“.

The publication had a circulation of 600 and the young author wasn’t paid, but he knew what it all meant.

Above: Monthly Magazine (1796 – 1843) issue, 1 February 1810

In the preface of the cheap edition of The Pickwick Papers, Dickens tells us that he practically smuggled the piece into the magazine’s offices:

“It was dropped stealthily one evening at twilight, with fear and trembling, into a dark letter box, in a dark office, up a dark court in Fleet Street.”

The piece’s emergence into print was an occasion of some emotion:

“I walked down to Westminster Hall and turned into it for half an hour, because my eyes were so dimmed with joy and pride, that they could not bear the street and were not fit to be seen there.”

More pieces for the Monthly Magazine followed.

These were comic stories, which owed a lot to the theatrical farces so common on the London stage.

It was at the end of one of these pieces, published in May 1834, that he signed his name as “Boz“, the nom de plume by which he first began to establish his reputation and indeed his brand.

Boz being a family nickname he employed as a pseudonym for some years.

Dickens apparently adopted it from the nickname “Moses“, which he had given to his youngest brother Augustus Dickens, after a character in Oliver Goldsmith’s The Vicar of Wakefield.

Above: Augustus Dickens (1827 – 1866)

When pronounced by anyone with a head cold, “Moses” became “Boses“—later shortened to Boz.

As “Boz“, Dickens began to collect readers.

He was given further opportunities to please them.

Dickens began to write occasional pieces for the Morning Chronicle in addition to his reporting.

These were his “sketches” – informal surveys of parts of London, London themes or observations of London people, held together by a conversational tone rather than a narrative: a Londoner talking to Londoners.

When an evening sister paper to the Morning Chronicle was launched, Dickens obtained a salary to continue his writing explorations in the same vein.

Above: London, 1886

The increasing exposure brought Dickens to the attention of Harrison Ainsworth, a writer not much read today, but a real star of the literary scene at this time.

Ainsworth admired Boz‘s work and introduced Dickens to his own publisher John Macrone.

Above: William Harrison Ainsworth (1805 – 1882)

Soon a collected volume of the newspaper and magazine pieces with drawings of George Cruikshank, the leading illustrator of the day, was published in February 1836.

Sketches by Boz sold so well that a second edition was needed that year and two more in 1837.

As the first edition of Sketches by Boz emerged in 1836, Dickens was approached by the publishers Chapman and Hall.

They came with an idea that had been proposed to them in turn by a well-known illustrator, Robert Seymour.

The plan went like this:

Seymour would produce a series of engravings depicting the amusing mishaps attending a club of Cockney sportsmen – men from the new middle classes, with money to spend on the aristocratic pursuits of previous generations: hunting, shooting and fishing.

These illustrations would be published as a monthly serial.

Would Dickens care to write some text to help string the images together?

Fourteen pounds a month might be possible.

No one really knows what or how much Dickens saw in this offer at the time.

He liked the money.

He was told that serials were a “low, cheap form of publication” that would ruin him.

The fact that he kept all his other irons in the fire suggests that he did not count too much on the new venture establishing his reputation.

But that is exactly what it did.

He claims, in the preface to The Pickwick Papers, that he recognized that the idea wouldn’t do:

“I objected, on consideration, that although born and partly bred in the country I was no great sportsman, that the idea was not novel, and had already been much used, that it would infinitely better for the plates to arise naturally out of the text, and that I should like to take my own way….”

At first sales were disappointing, but by the end of its run in November 1837, The Pickwick Papers was selling 40,000 copies per month, it had been adapted for the stage many times over and the words of its characters seemed to be on everyone’s lips – as was the name of its young author.

After their 1836 wedding, Charles took Catherine to a set of chambers he was renting in Furnival’s Inn, one of the inns of court, the traditional home of English law practice and accommodation for many non-lawyers too.

As The Pickwick Papers started bringing in a more secure income, Charles set his sights on more substantial living quarters.

These turned out to be at 48 Doughty Street, into which Catherine and Charles moved with their son Charley in March 1837.

Above: 48 Doughty Street, London

They took in Catherine’s younger sister Mary Hogarth, who had supported Catherine during her first pregnancy.

It was not unusual for a woman’s unwed sister to live with and help a married couple.

Dickens became very attached to Mary.

She inspired characters in many of his books.

Mary is seen as the inspiration for Rose Maylie in Oliver Twist.

She is also seen as the inspiration for Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop.

Nell had many traits that Dickens associated to Howarth, including describing Nell as “young, beautiful and good“.

Other characters believed to have been inspired by Mary include:

- Kate Nickleby, the 17-year-old sister of the hero of the novel Nicholas Nickleby

- Agnes Wickfield, the heroine in David Copperfield

- Ruth Pinch from Martin Chuzzlewit

- Lilian, the child who appears in Trotty Veck’s visions in The Chimes

- Dot Peerybingle, the sister in The Cricket on the Hearth.

Above: Mary Hogarth (1819 – 1837)

Unlike Mary, Dickens’ wife Catherine does not appear to have been the inspiration for any of his characters.

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London, famed as a fashionable residential area and as the home of numerous prestigious cultural, intellectual and educational institutions.

It is bounded by Fitzrovia to the west, Covent Garden to the south, Regent’s Park and St. Pancras to the north, and Clerkenwell to the east.

Bloomsbury is home of the British Museum, the largest museum in the United Kingdom, and numerous educational institutions, including the University College London, the University of London, the New College of the Humanities, the University of Law, the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, and many others.

Above: The British Museum, London

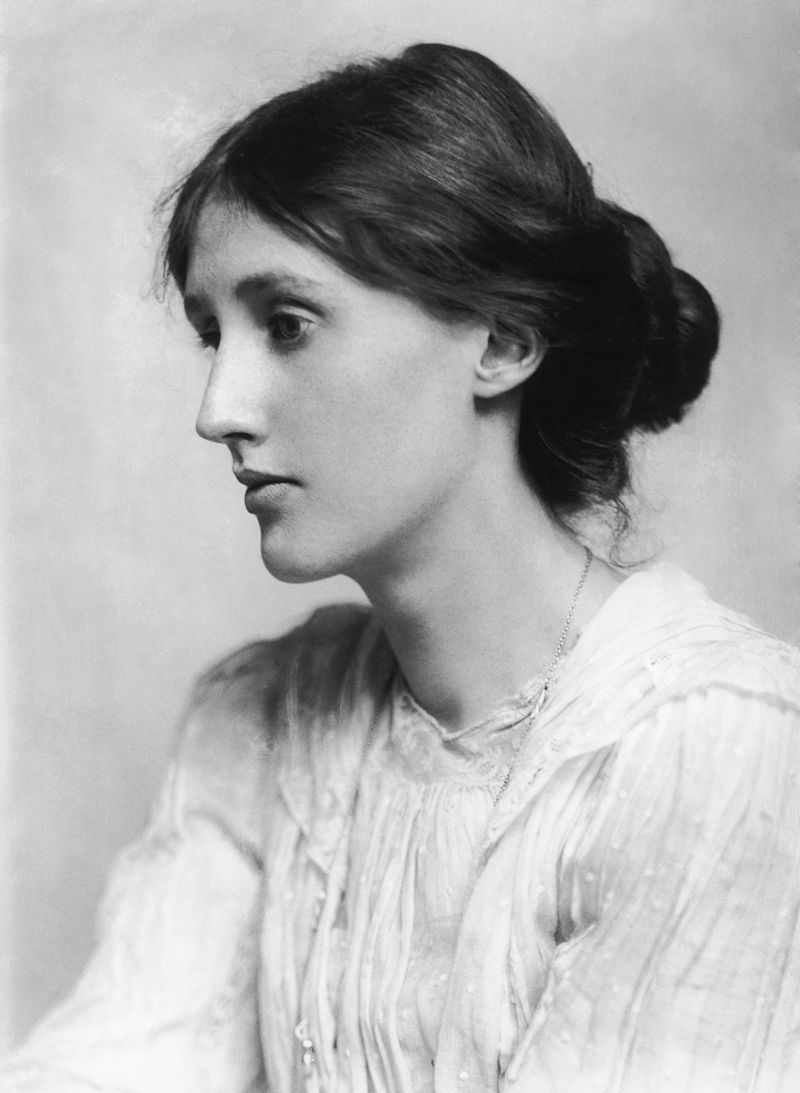

Bloomsbury is an intellectual and literary hub for London, as home of world-known Bloomsbury Publishing, publishers of the Harry Potter series, and namesake of the Bloomsbury Set, a group of famous British intellectuals, including author Virginia Woolf and economist John Maynard Keynes, among others.

Above: Virginia Woolf (1882 – 1941)

Bloomsbury began to be developed in the 17th century under the Earls of Southampton, but it was primarily in the 19th century, under the Duke of Bedford, which the district was planned and built as an affluent Regency era residential area by famed developer James Burton.

The district is known for its numerous garden squares, including Bloomsbury Square, Russell Square and Tavistock Square, among others.

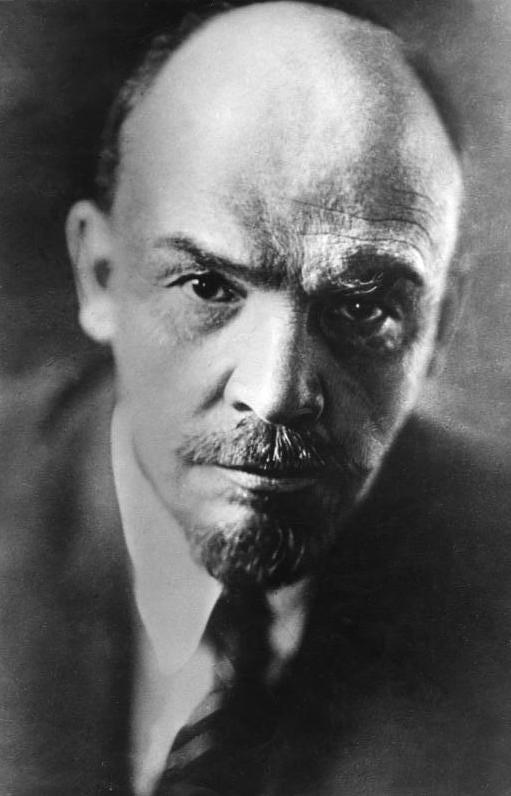

Notable residents of Bloomsbury have included J.M. Barrie (Peter Pan), Charles Darwin, Charles Dickens, Ricky Gervais, Vladimir Lenin, Bob Marley, Catherine Tate (Donna Noble, Doctor Who) and William Butler Yeats.

Above: Vladimir Lenin (1870 – 1924)

Despite a plethora of blue plaques, Bloomsbury boasts just one literary museum, the Charles Dickens Museum, the only one of the writer’s fifteen London addresses to survive intact.

Doughty Street was a well-to-do gated Georgian street when Dickens – flush with the success of his first two published works – moved here in 1837.

The family lived in this light and airy house for two years, during which he completed Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby and worked on Barnaby Rudge.

Catherine gave birth to two children in the bedroom here.

On Saturday, 6 May 1837, Charles took Catherine and Mary to the theatre.

They returned home in good spirits, enjoyed some supper and a drink together and went to bed at one in the morning.

A few moments later Charles heard a cry from Mary’s bedroom and hurried in to find her still in her day clothes and visibly ill.

Catherine came to see what was wrong.

Charles said afterwards that they had no idea there was anything seriously the matter with Mary, but that they sent for medical assistance to be on the safe side.

Whatever Dr. Pickthorn did had no effect, yet still there seemed no cause for alarm.

Mary was, after all, only 17 years old and until then had been in perfect health.

Fourteen hours went by before Mary sank under the attack and died – died in such a calm and gentle sleep, that although Charles had held her in his arms for some time before, when she was certainly living (for she swallowed a little brandy from his hand) Charles continued to support her lifeless form, long after her soul had fled to Heaven.

This was about 3 o’clock on Sunday afternoon.

“Thank God she died in my arms and the very last words she whispered were of me.“, Charles told fellow reporter and friend Tom Beard.

Before Charles laid Mary’s body down he was able to remove a ring from her finger and put it on one of his own.

And there it stayed for the rest of his life.

Above: Mary’s bedroom, Charles Dickens Museum

Mary’s death is fictionalized as the death of Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop.

The building at 48 Doughty Street was threatened with demolition in 1923, but was saved by the Dickens Fellowship, founded in 1902, who raised the mortgage and bought the property.

The house was renovated and the Dickens House Museum was opened in 1925, under the direction of an independent trust, now a registered charity.

Above: Study, Charles Dickens Museum

48 Doughty Street is presented as far as possible in its inhabited state, the idea being to give the impression that the Dickens family is still resident.

Much of the house’s furniture belonged, at one time or another, to Dickens, and the house also owns the earliest known portrait of the writer (a miniature painted by his aunt Mary Allen in 1830).

Above: Charles Dickens

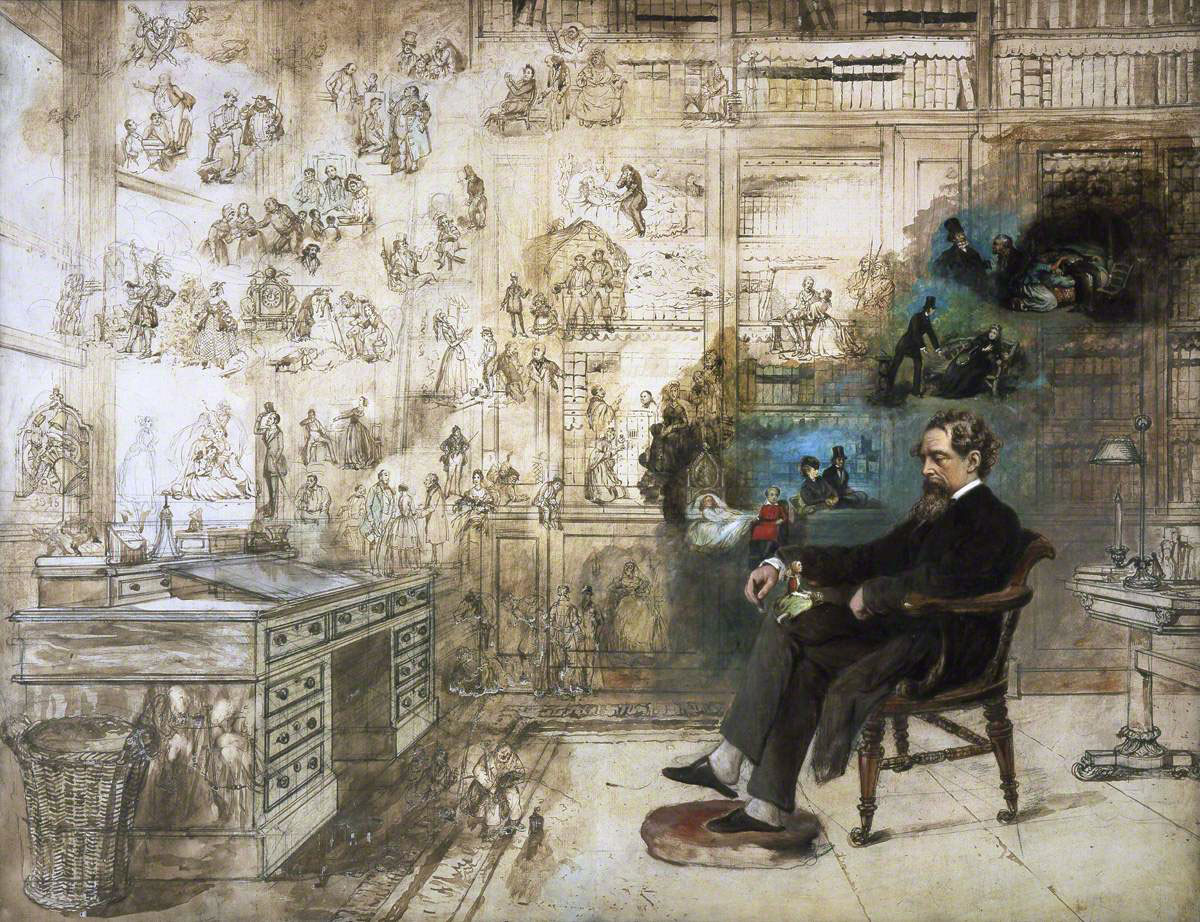

Perhaps the best-known exhibit is the portrait of Dickens known as Dickens’s Dream by R. W. Buss, an original illustrator of The Pickwick Papers.

This unfinished portrait shows Dickens in his study at Gads Hill Place surrounded by many of the characters he had created.

The painting was begun in 1870 after Dickens’s death.

Above: Dickens’ Dream, Robert William Buss

(Gads Hill Place in Higham, Kent, sometimes spelt Gadshill Place and Gad’s Hill Place, was the country home of Charles Dickens.

Today the building is the independent Gad’s Hill School.

The house was built in 1780 for a former Mayor of Rochester, Thomas Stephens, opposite the present Sir John Falstaff Public House.

Gad’s Hill is where Falstaff commits the robbery that begins Shakespeare’s Henriad trilogy (Henry IV: Part 1, Henry IV: Part 2 and Henry V). )

Above: Gad’s Hill Place, Rochester

Other notable artefacts in the Museum include numerous first editions and original manuscripts as well as original letters by Dickens, and many personal items owned by Dickens and his family.

The only known item of clothing worn by Dickens still in existence is also displayed at the Museum.

This is his Court suit and sword, worn when Dickens was presented to the Prince of Wales in 1870.

The Charles Dickens Museum also owns the adjacent house, #49, where they stage special exhibitions, house the bookshop and have a lovely café with free Wifi.

There runs within both London and Rochester (where Charles spent the last years of his life) a Dickens Trail.

On London’s Dickens Trail, there is:

- the Old Curiosity Shop (currently a shoe shop) on Lincoln’s Inn Fields, the inspiration of Dickens’ novel of the same name

- the atmospheric Inns of Court (once the headquarters of the Knights Templar) which feature in several Dickens novels

- Nancy’s Steps, where Nancy tells Rose Maylie Oliver’s story in Oliver Twist

- the evocative dockland area east of Shad Thames where Bill Sykes (also of Oliver Twist) had his hide-out.

(This dockland area, known as China Wharf – today very photogenic with its stack of semicircular windows picked out in red – was once dubbed “the very capital of cholera“.

In 1849, the Morning Chronicle described it thus:

“Jostling with unemployed labourers of the lowest class, ballast heavers, coal-whippers, brazen women, ragged children, and the very raff and refuse of the river, the visitor makes his way with difficulty along, assailed by offensive sights and sounds from the narrow alleys which branch off.”

This was the location of Dickens’ fictional Jacob’s Island, a place with “every imaginable sign of desolation and neglect“, where Bill Sykes met his end in Oliver Twist.)

Above: China Wharf, London

Charles John Huffam Dickens (7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic.

He created some of the world’s best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian era.

His works enjoyed unprecedented popularity during his lifetime, and, by the 20th century, critics and scholars had recognised him as a literary genius.

His novels and short stories are still widely read today.

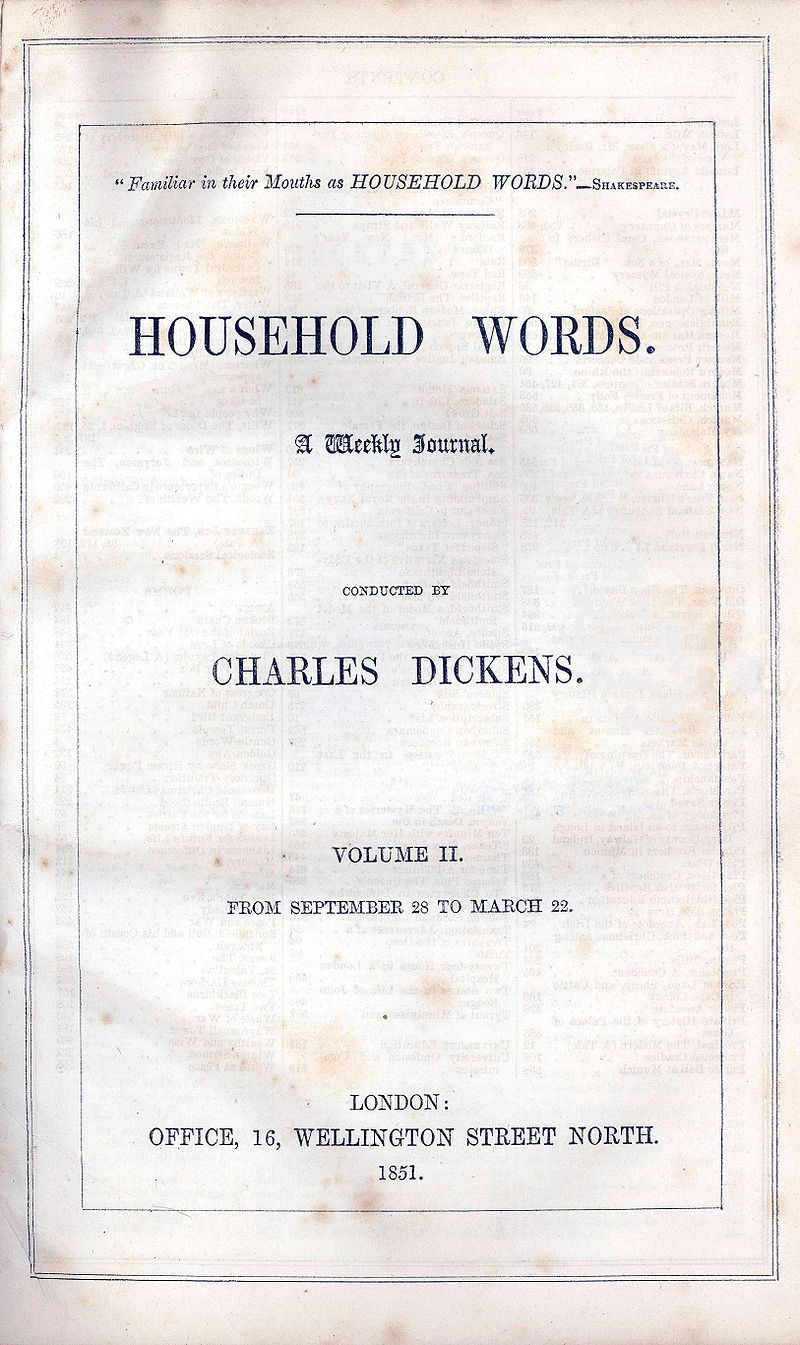

Despite his lack of formal education, he edited a weekly journal for 20 years, wrote 15 novels, five novellas, hundreds of short stories and non-fiction articles, lectured and performed readings extensively, was an indefatigable letter writer and campaigned vigorously for children’s rights, education and other social reforms.

Above: Charles Dickens, 1842

Dickens’s literary success began with the 1836 serial publication of The Pickwick Papers.

Within a few years he had become an international literary celebrity, famous for his humour, satire and keen observation of character and society.

His novels, most published in monthly or weekly instalments, pioneered the serial publication of narrative fiction, which became the dominant Victorian mode for novel publication.

Cliffhanger endings in his serial publications kept readers in suspense.

The instalment format allowed Dickens to evaluate his audience’s reaction, and he often modified his plot and character development based on such feedback.

For example, when his wife’s chiropodist expressed distress at the way Miss Mowcher in David Copperfield seemed to reflect her disabilities, Dickens improved the character with positive features.

His plots were carefully constructed and he often wove elements from topical events into his narratives.

Above: Charles Dickens, 1850

Masses of the illiterate poor chipped in ha’pennies to have each new monthly episode read to them, opening up and inspiring a new class of readers.

His 1843 novella A Christmas Carol remains especially popular and continues to inspire adaptations in every artistic genre.

Oliver Twist and Great Expectations are also frequently adapted and, like many of his novels, evoke images of early Victorian London.

His 1859 novel A Tale of Two Cities (set in London and Paris) is his best-known work of historical fiction.

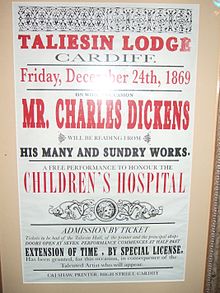

The most famous celebrity of his era, public demand saw him undertake a series of public reading tours in the later part of his career.

Dickens has been praised by many of his fellow writers—from Leo Tolstoy to George Orwell, G. K. Chesterton and Tom Wolfe—for his realism, comedy, prose style, unique characterisations and social criticism.

However, Oscar Wilde, Henry James and Virginia Woolf complained of a lack of psychological depth, loose writing and a vein of sentimentalism.

Above: Dickens’ chair, Charles Dickens Museum

The term Dickensian is used to describe something that is reminiscent of Dickens and his writings, such as poor social conditions or comically repulsive characters.

There is much in Charles Dickens’ life before and up to his residency at 48 Doughty Street that I can relate with.

Charles came from a large family, as did I, but like the titular hero of Oliver Twist it was not until later in my life did I come to realize that I was neither an orphan (nor an only child) as far as my biological heritage went.

My first work during my school years was labour intensive like Charles’ was.

While his was labouring in a blacking factory, mine was summer employment as a farmhand.

(A position I occasionally returned to when financing my travels.)

Like Charles, I spent much of the early years of my life outdoors when I wasn’t reading voraciously.

The boy Charles read Tobias Smollett and Henry Fielding and The Arabian Nights.

I read Charles Dickens, Robert Louis Stephenson and the adventures of the Hardy Boys.

Charles was separated from his family by mounting debts and living beyond one’s means.

It is said that these were the cause of my biological parents’ break-up and it was the prevention of these to my foster parents that led to my being taken in for the provincial support the government provided for my care.

Unlike Charles, I was never small for my age and I would by the age of 14 surpass Charles’ adult height of 5’9″ to reach my current height of 6’4″, but, like Charles, I had felt that I was a “not-over-particularly-taken-care-of boy“.

After my secondary and post-secondary studies, I, like Charles, worked as a clerk, but what for him would be a brief two years would be for me always a position to return to between my travels.

I have worked as a clerk for a customs broker, federal government departments and for a registered charity.

More akin to George Orwell, I would later work as a teacher and a restaurant worker, but in a Dickensian vein, I have written (sometimes for money, sometimes for exposure) for local newspapers and school publications.

I have never achieved great fame, but then neither have I greatly sought it to the extent that Dickens did.

What I have always admired about Dickens and his works are:

- his humour, satire and keen observation of character and society.

- his carefully constructed plots wherein he often wove elements from topical events into his narratives.

- his realism, comedy, prose style, unique characterisations and social criticism.

- his walking which led to his descriptions of the neglected and forgotten corners of London.

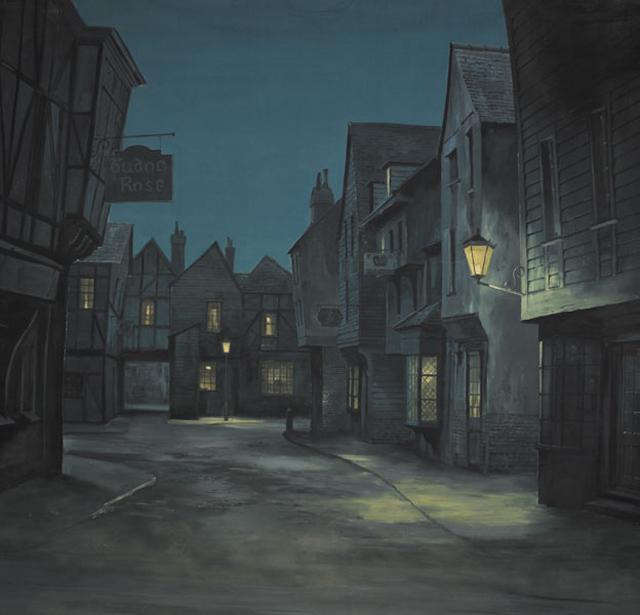

“Cities, like cats, will reveal themselves at night.“, wrote the poet Rupert Brooke.

London’s own Geoffrey Chaucer, William Shakespeare, William Blake and Thomas De Quincey were all night time perambulators, but of those who walk the streets at night the supreme nightwalker was Charles Dickens.

In Great Expectations (1861), Pip at one point visits Miss Haversham in her home in Kent in order to inform her and her ward Estella, with whom he is still madly in love, that he has finally discovered the identity of his benefactor, the convict Magwitch.

Pip confirms that, because he knows Miss Haversham was not responsible for his transformation into a gentleman, he realizes that she and Estella have all along treated him not as their protegé but “as a kind of servant, to gratify a want or whim“.

It is on this occasion, too, that Estella admits she is to be married, as Pip feared, to the odious and oafish aristocrat Bentley Drummle.

Thus discarded, and in a deeply disconsolate state of mind, Pip escapes from Satis House and, as the afternoon light thickens, hides himself for a time “among some lanes and bypaths“.

Then, in a moment of decision, he strikes off “to walk all the way to London“.

“I could do nothing half so good for myself as tire myself out.”, he decides.

It is “past midnight” when he eventually crosses London Bridge.

Four years later, Dickens made roughly the same journey on foot, in reverse.

One night in October 1857, when he was in his mid-forties, Dickens retired to bed in the family home in Bloomsbury, but found himself completely unable to get to sleep.

He had suffered from intermittent insomnia throughout his adult life, but on this occasion he felt particularly agitated.

He did not feel at home at home.

So at 0200 Dickens climbed out of bed, dressed in warm clothes and set off through the gaslit streets of the city.

Dickens had written more than two decades earlier:

“The streets of London, to be beheld in the very height of their glory, should be seen on a dark, dull, murky winter’s night.

When the heavy, lazy mist, which hangs over every object, makes the gas lamps look brighter.”

In the damp silence of the autumn night, beneath the scuffing sound of his boots on the stone pavements, Dickens would have heard the gas whispering its secrets in the softly rasping pipes.

Heading south in the direction of the Thames, Dickens walked through London directly to Gad’s Hill Place, his country residence in Kent.

Like Pip’s journey through the night, it was a distance of some 30 miles.

Catherine and Charles had been….prolific – ten children – “the largest family ever known with the smallest disposition to do anything for themselves” as Dickens later described them – and 15 novels, each published in monthly (or weekly) installments, which were awaited with baited breath by the public.

Then in 1857, at the peak of his career, Dickens fell in love with the actress, Ellen Ternan.

Charles was 45, Ellen just 18.

Above: Ellen Ternan (1839 – 1914)

On the evening of his nightwalk, Catherine and Charles quarrelled.

They were becoming inrcreasingly estranged, partly because of his relationship with Ellen.

For this reason, Charles visited Tavistock House, their home at this time, only rarely.

Above: Tavistock House, London

Charles spent most of the autumn of 1857 at Gad’s Hill Place.

When he needed to be in central London, he tended to stay in a bachelor flat at the offices of his periodical, Household Words.

It was shortly after Charles insisted on partitioning the bedroom he shared with Catherine so that they could sleep separately.

The nighttime journey on foot to Gad’s Hill Place, driven by an acute sense of anguish and guilt, took Dickens little more than seven hours.

(According to present day Google Maps, the same journey normally takes 9.5 hours.)

Above: Google Maps logo

Dickens was a fast walker, who took pride in the fact that he could sustain a pace of at least four miles an hour across long distances.

(In my walking days my average pace was 3 mph and on a descent 5 mph.)

Above: Canada Slim, The Dutton Advance, 6 March 1991

His friends frequently complained of the speed and impatience with which he walked.

Above: Charles Dickens

Edward Johnson, one of his biographers, wrote:

“Sometimes his perspiring companions gave way to blisters and breathlessness.”

Charles himself was boastful of his feats as a pedestrian.

He professed in 1860:

“So much of my travelling is done on foot that if I cherished betting propensities, I should probably be found registered in sporting newspapers as the Elastic Novice, challenging all 11-stone mankind to competition in walking.”

No doubt he secretly harboured dreams of bettering Captain Barclay, a celebrated athlete who, in 1809, when pedestrianism first became a sporting activity, walked a thousand miles in a thousand hours for a thousand guineas.

Above: Captain Robert Barclay-Allardyce (1779 – 1854), the celebrated pedestrian

In the late 1850s, Dickens remained a fit man precisely because he insisted on walking, both in London and in the countryside, whenever he could find the opportunity.

Even so, he was increasingly afflicted with ill health at this time.

His symptoms included neuralgic and rheumatic pains.

His feet also troubled him.

According to biographer Claire Tomalin:

“First his left foot, and then his right, took to swelling intermittedly, becoming so painful that during each attack he became unable to take himself on the great walks that were essential part and pleasure of his life.”

Dickens had gout, though he was reluctant to accept the idea, claiming instead that he contracted the pain because he had incautiously walked in snowy conditions.

This did not deter him from walking in all conditions, clement or inclement.

G.K. Chesterton, identifiying a “streak of sickness” in Dickens, which he detected in the novelist’s “fervid” intelligence, nonetheless confirmed that “he suffered from no formidable malady and could always through life endure a great deal of exertion, even if it was only the exertion of walking violently all night.”

Above: Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874 – 1936)

For John Hollingshead, who had been apprenticed to Dickens on Household Words, and who therefore saw a good deal of him in the 1850s, this proclivity for “violent walking” was itself a malady.

Hollingshead recalled in retrospect that “when Dickens lived in Tavistock House he developed a mania for walking long distances, which almost assumed the form of a disease.”

“When he was restless, his brain excited by struggling with incidents or characters in the novel he was writing, he would frequently get up and walk through the night over Waterloo Bridge, along the London, New Kent and Old Kent Roads, past all the towns on the old Dover High Road, until he came to his roadside dwelling (Gad’s Hill Place).

His dogs barked when they heard his key in the wicket-gate.

His behaviour must have seemed madness to the ghost of Sir John Falstaff.”

(Gad’s Hill Place stood opposite the Falstaff Inn, formerly a notorious haunt of robbers and highwaymen.)

Above: John Hollingshead (1827 – 1904)

It is likely, then, that Dickens conducted his 30-mile nightwalk to Kent on more than one occasion.

But Dickens’ celebrated feat on that night in October 1857 was less about overcoming physical afflictions than capitulating to his psychological ones.

This was a flight both from his everyday life and from his self.

From an early age Charles had been running away from something, or walking “fast and far” from something.

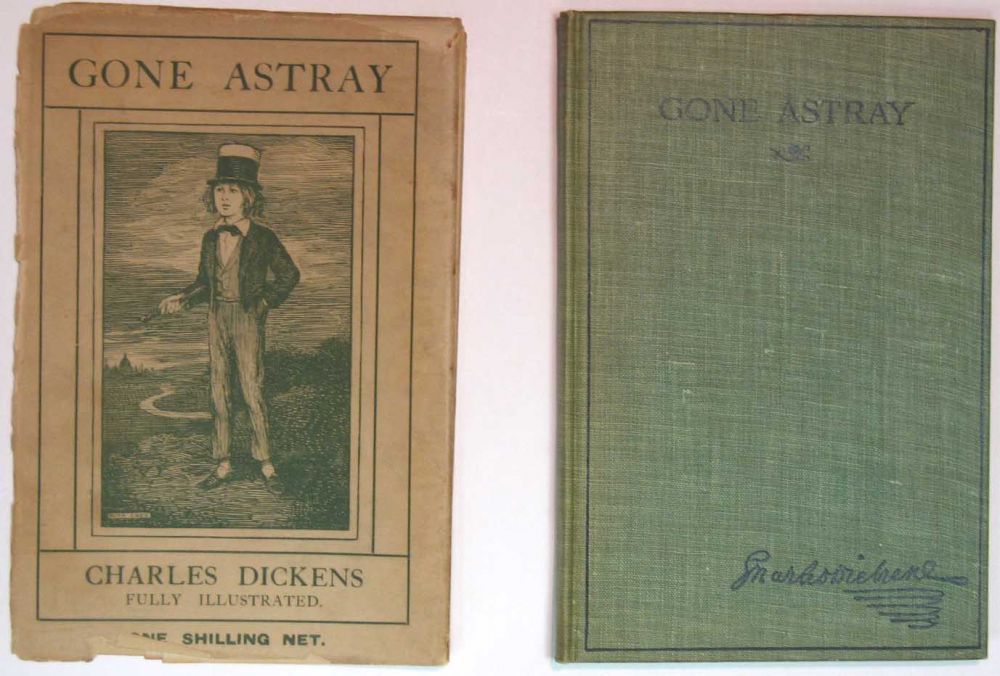

“Going astray“, he called it.

In an article entitled “Going Astray“, printed in Household Words in 1853, Dickens described how he had “got lost one day in the City of London” as an 8-year-old child and roamed and strayed and strolled through London’s precincts all day and into the night, until he found a watchman.

“I have gone astray since, many times, and farther afield.“, Dickens concludes with a certain sad pride.

Chesterton argued that Dicken’s originality and genius resided in the fact that he possessed, “in the most sacred and serious sense of the term, the key of the street.”

“Few of us understand the street.

Even we step into it, as into a house or a room of strangers.

Few of us see through the shining riddle of the street, the strange folk that belong to the street only – the street-walker or the street Arab, the nomads, who generation after generation, have kept their ancient secrets in the full blaze of the sun.

Of the street at night many of us know even less.

The street at night is a great house locked up.

But Dickens had, if ever man had, the key of the street.

His stars were the lamps of the street.

His hero was the man in the street.

He could open the inmost door of his house – the door that leads into that secret passage which is lined with houses and roofed with stars.”

Night Walks, first published in All the Year Round in 1860 and then reprinted in The Uncommercial Traveller in 1861, was Dickens’ finest, most haunting piece of non-fictional prose.

At once impressionistic and replete with intensely related detail, it relates his experiences on the streets of the capital between half past midnight (0030) and the moment when “the conscious gas begins to grow pale with the knowledge that daylight is coming.”

A sense of solitude echoes through his sentences, empty and hollow as the midnight streets through which he walks.

“When a church clock strikes, on homeless ears in the dead of the night, it may be at first be mistaken for company, but as the spreading circles of vibration echo out into eternal space, the mistake is rectified and the sense of loneliness is profounder.”

Dickens confesses to have discovered a lonely sense of community in the cold depths of the London night, among men defined by “a tendency to lurk and lounge, to be at street corners without intelligible reason“.

“My principal object being to get through the night, the pursuit of it brought me into sympathetic relations with people who have no other object every night of the year.”

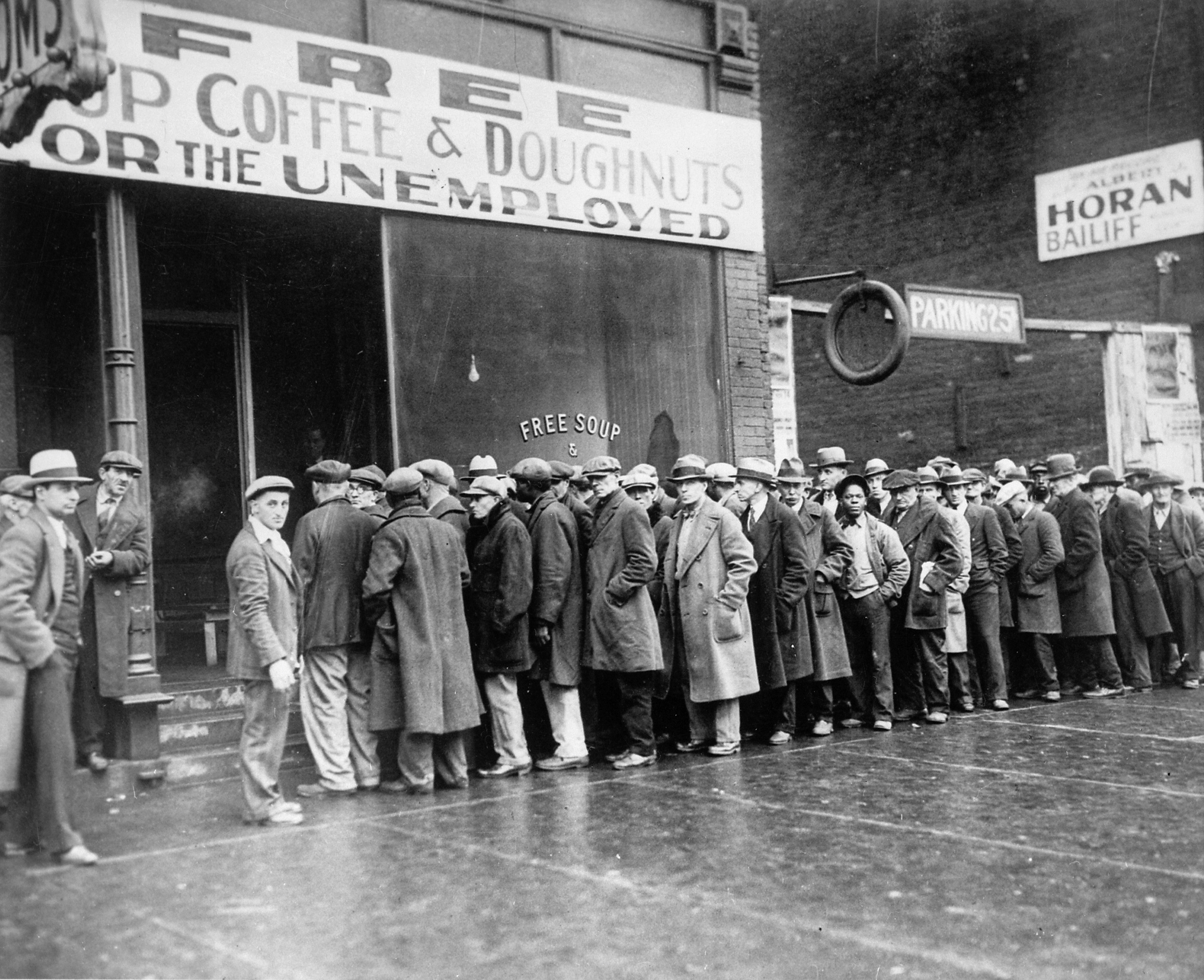

These are the everyday casualities of life in the capitalist metropolis – the victims of unemployment, addiction and other symptoms of social and spiritual alienation.

The homeless must conquer time and defend themselves against its blank emptiness, from minute to minute, moment by moment, the shame, desertion, wretchedness and exposure of the great capital, the wet, the cold, the slow hours and the swift clouds of the dismal night.

For the police, the proof of a home, a legal nocturnal place to stay, is the precondition for the recognition of existence.

So the situation of homelessness, roaming the night without aim, without rest, represents exclusion from society.

It is a form of non-existence, non-being, the outer limits of society’s psychological and sociological borderland, the hinterland of humanity, the dark hollow interior of human nature.

London is a city where 55% of people are not ethnically white British, nearly 40% were born abroad, and 5% are living illegally in the shadows.

Every week 2,000 migrants unload at Victoria Coach Station, tens of thousands of migrants arriving here every year.

But who can trust statistics?

You will never understand what it means to be a beggar until you have slept on the streets.

They sleep in front of the glare of shop windows, for the light lends a sense of safety.

Crackheads and Roma, street life, disorientation, a jumble of faces, an eternal rumble of traffic, where working girls sell their bodies and throw in their souls for free, the rhythm of the streets, a never sated drumbeat.

Ute (my wife) and I on London evenings are one of many after-dinner couples strolling along.

I hear others with their contempt and disgust regard the beggars who congregate upon the concrete like lost church mice, like mangy parasites, cosmopolitan cockroaches, best belittled than assisted.

They are the invisible, because we choose to ignore them.

They are painful reminders of our privileged life that they cannot imagine having or, if once had, reacquiring.

They are the old and the prematurely aged, shuffling and stumbling, snuffling and sniffing, pleading for pennies from those whose hearts are void of compassion.

Washed-up soiled souls marooned, listless and almost lifeless, easy prey to those who would use them for cruel sport, they lie beneath walls smeared in blood and feces upon flattened cardboard boxes that soften the sidewalk.

Human rubbish amidst human refuse, they are gaunt faces with sunken eyes, needing to beg to survive, to live, to exist, but to beg is to break the law.

What is earned is confiscated.

Law and order trumps love and outreach.

They see the beggar as an offense not as a fellow human being.

Those without homes are an invisible city deliberately unseen by the lucky with lodgings.

Charles Dickens’ home is remembered as I hold my wife’s hand tightly to lend ourselves courage to encounter what we do not comprehend.

Charles feared poverty, was obsessed with money, felt that unease that only those who have raised themselves out from poverty can truly understand.

But his talent, hard work, perseverance and good fortune never required a return to a hand-to-mouth, payment-to-payment survival.

He encountered the homeless and destitute during his night walks but was never reduced to joining their ranks.

Above: Charles Dickens

My wife and I have London lodgings during our sojourn here and a warm comfortable flat awaiting our return to Switzerland.

I too have known a poverty of sorts, though my begging was limited to government assistance and hitching rides and seeking emergency overnight shelter in the places where rides left me.

In my long-distance walking days I slept wherever I could and rarely needed the tent I carried upon my backpack.

Like those migrants of London for whom hope remains despite their desperate circumstances, I worked where and when I could, sometimes in the safety of the law, sometimes not.

Though I have never been much of an evening perambulator I have nonetheless encountered the homeless in more than a few cities I have visited.

I see it regularly amongst the Roma in Konstanz and I give as prudently as I can when I encounter the beggar Bruno in St. Gallen.

I remember the helpless and hapless of London and Paris, Seoul and Istanbul, Naples and New York.

Above: The Old Beggar of Bordeaux, Louis Dewis, 1916

I think of Oliver Twist.

“Advancing to the master, basin and spoon in hand, said, somewhat alarmed at his own temerity:

“Please, sir, I want some more.” ”

Above: Mark Lester as Oliver Twist, Oliver!, 1968

Everyone’s hungry for something.

Sources: The Rough Guide to London / Matthew Beaumont, Night Walking: A Nocturnal History of London / Jeremy Clarke, The Charles Dickens Miscellany / Charles Dickens, Night Walks / Ben Judah, This Is London / Claire Tomalin, Charles Dickens: A Life