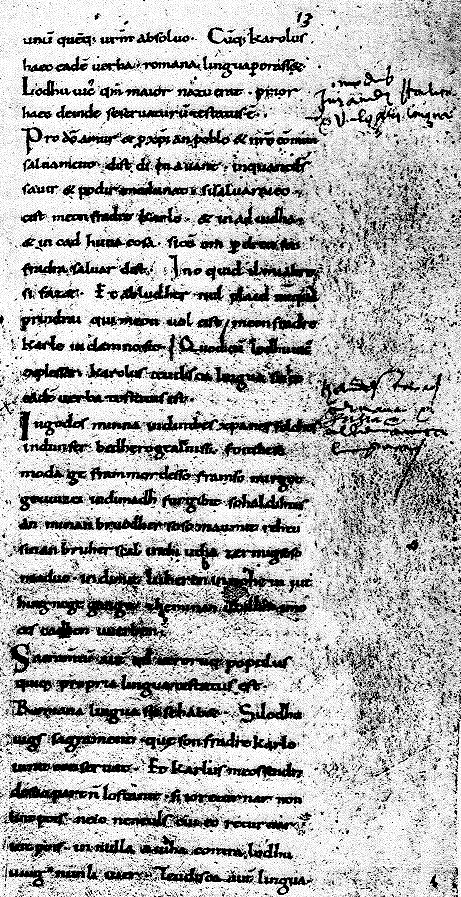

Landschlacht, Switzerland, Tuesday 8 September 2020

It must be difficult for followers of this first of two blogs to remain faithful and patient with the Chronicles of Canada Slim as they are not as often written as those of Building Everest.

To those who are new to the Chronicles, these posts are accounts of travels prior to the calendar year and have followed an alphabetical sequence of:

- Alsace

- Italy

- Lanzarote

- London

- Porto

- Serbia

- Switzerland

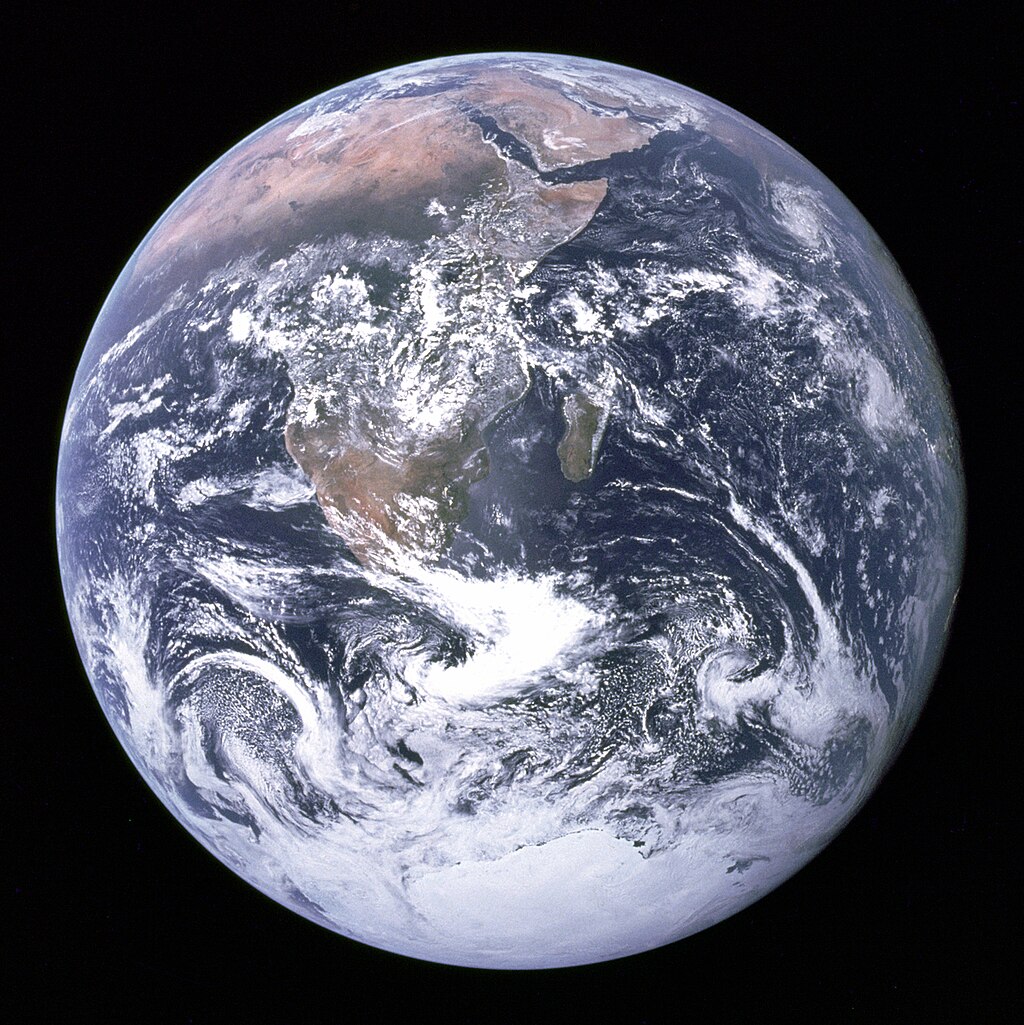

This post in the sequence is focused on Serbia and is the continuation of my story of a remarkable man and the museum in Belgrade that commemorates his achievements and prolongs the memory of the only Serbian (to date) to have won the Nobel Prize for Literature:

Ivo Andric.

Ivo Andrić (1892 – 1975) was a Yugoslav novelist, poet and short story writer who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1961.

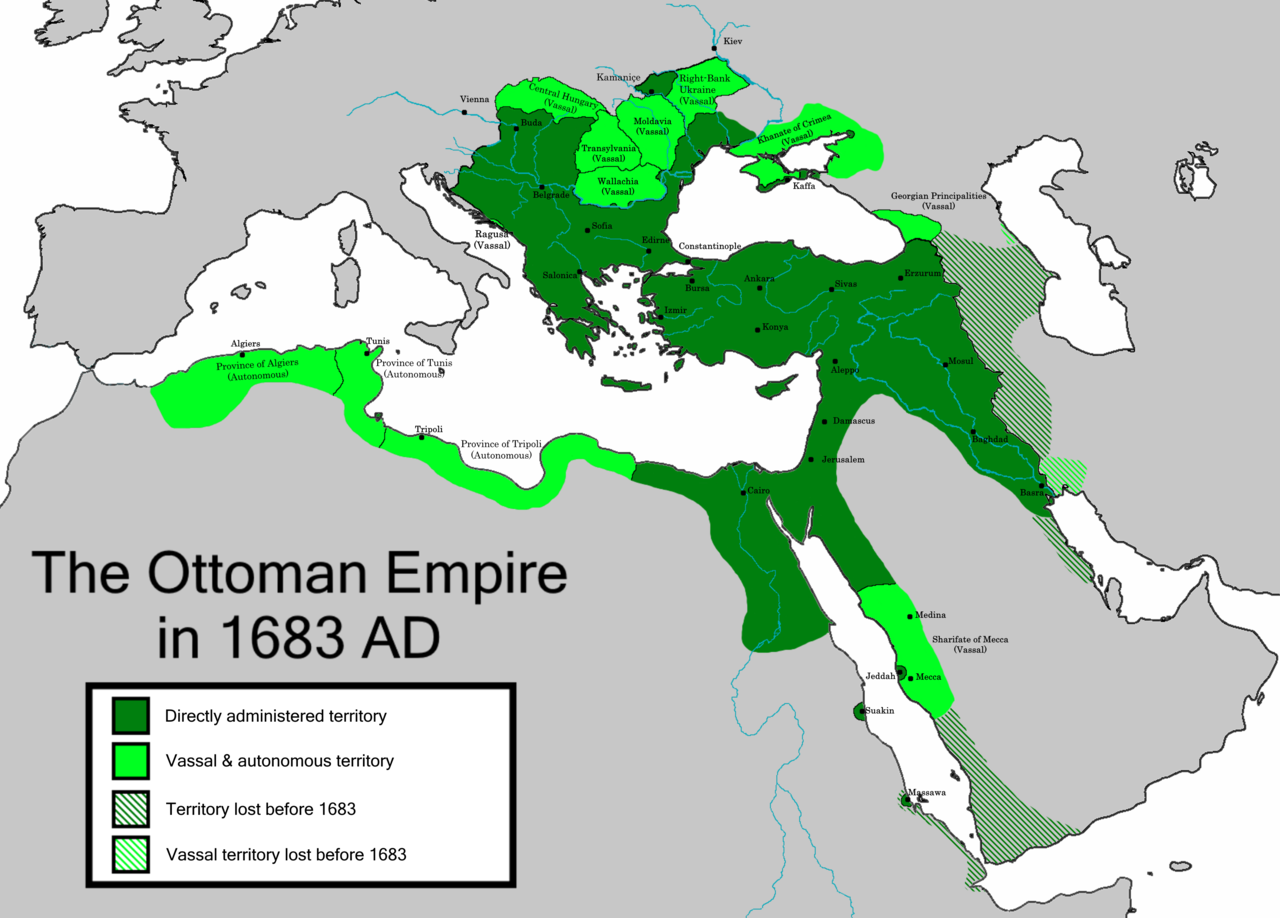

His writings dealt mainly with life in his native Bosnia under Ottoman rule.

Born in Travnik in the Austrian Empire, modern-day Bosnia, Andrić attended high school in Sarajevo, where he became an active member of several South Slav national youth organizations.

Above: The house in which Andric was born

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1914, Andrić was arrested and imprisoned by the Austro-Hungarian police, who suspected his involvement in the plot.

Above: The first page of the edition of the Domenica del Corriere, an Italian paper, with a drawing of Achille Beltrame depicting Gavrilo Princip killing Archduke Francis Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo

As the authorities were unable to build a strong case against him, he spent much of the war under house arrest, only being released following a general amnesty for such cases in July 1917.

After the war, he studied South Slavic history and literature at universities in Zagreb and Graz, eventually attaining his Ph.D. in Graz in 1924.

He worked in the diplomatic service of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 1920 to 1923 and again from 1924 to 1941.

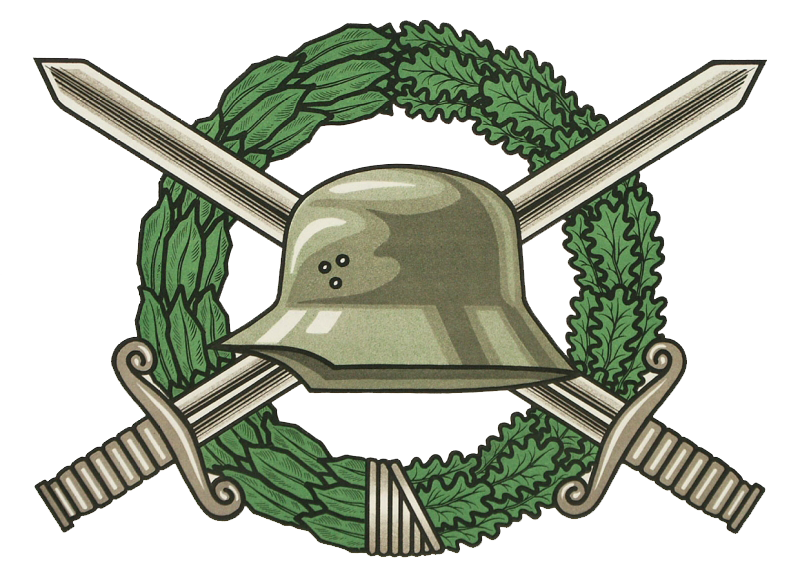

In 1939, he became Yugoslavia’s ambassador to Germany, but his tenure ended in April 1941 with the German-led invasion of his country.

Above: Coat of Arms of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

Shortly after the invasion, Andrić returned to German-occupied Belgrade.

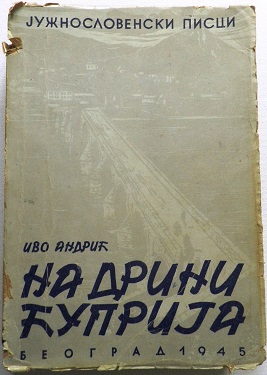

He lived quietly in a friend’s apartment for the duration of World War II, in conditions likened by some biographers to house arrest, and wrote some of his most important works, including Na Drini ćuprija (The Bridge on the Drina).

Above: Ivo Andrić monument in Belgrade, Serbia

Following the war, Andrić was named to a number of ceremonial posts in Yugoslavia, which had since come under communist rule.

In 1961, the Nobel Committee awarded him the Nobel Prize in Literature, selecting him over writers such as J. R. R. Tolkien, Robert Frost, John Steinbeck and E. M. Forster.

The Committee cited “the epic force with which he traced themes and depicted human destinies drawn from his country’s history“.

Afterwards, Andrić’s works found an international audience and were translated into a number of languages.

In subsequent years, he received a number of awards in his native country.

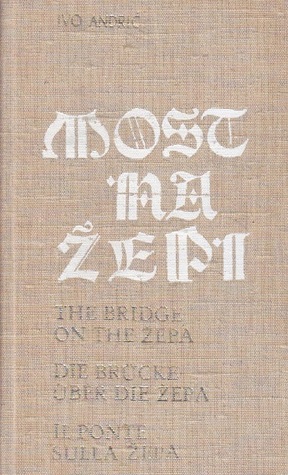

Above: Front cover art for The Bridge on the Drina written by Ivo Andrić

Andrić’s health declined substantially in late 1974.

He died in Belgrade the following March.

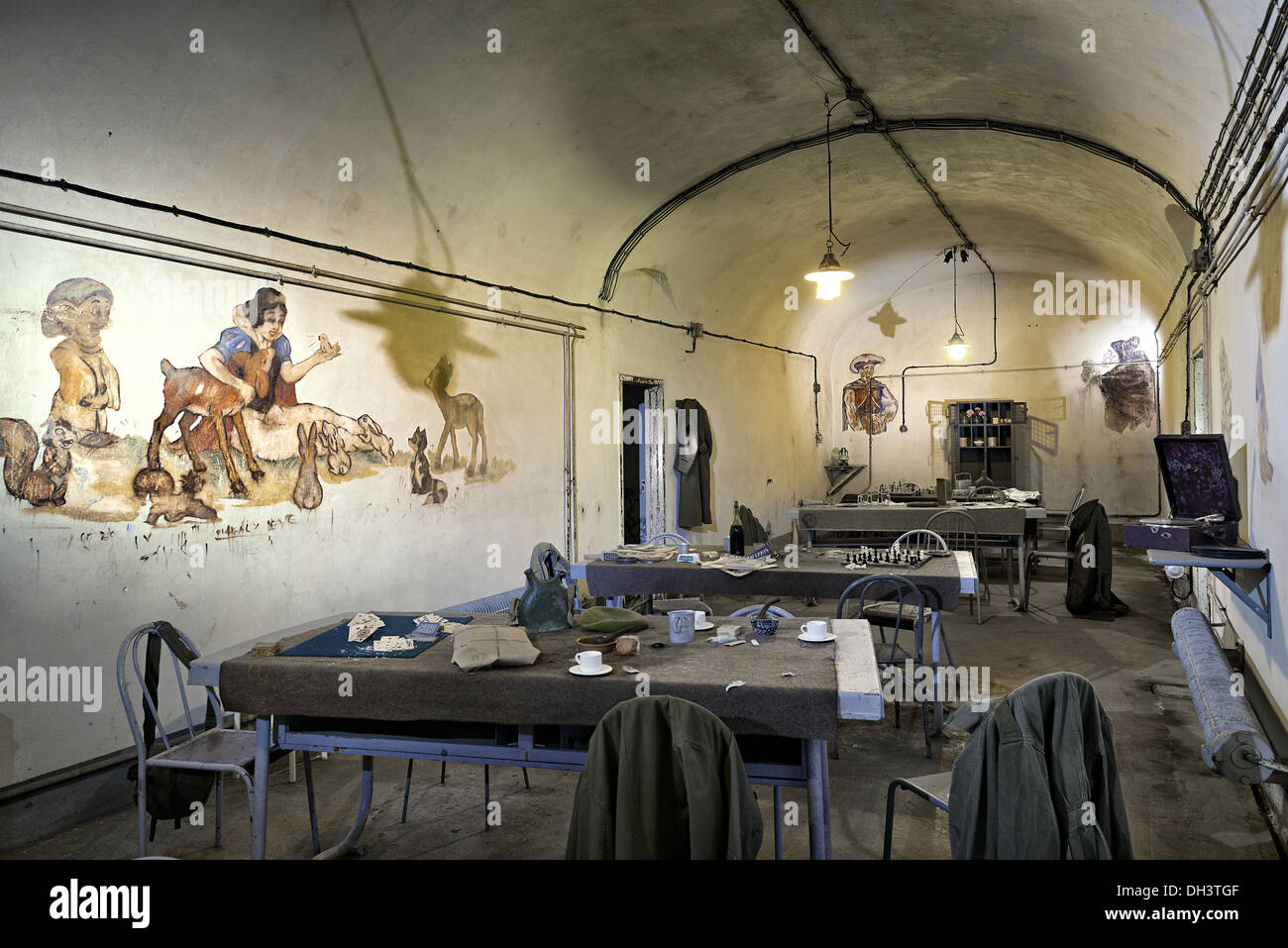

In the years following Andrić’s death, the Belgrade apartment where he spent much of World War II was converted into a museum and a nearby street corner was named in his honour.

It is this author’s apartment, this Ivo Andric Museum in Belgrade which I visited in the spring of 2018.

Above: Ivо Andric Museum Building, Belgrade, Serbia

A number of other cities in the former Yugoslavia also have streets bearing his name.

In 2012, filmmaker Emir Kusturica began construction of an ethno-town in eastern Bosnia that is named after Andrić.

Above: Main entrance of Andrićgrad, Bosnia and Herzegovina

As Yugoslavia’s only Nobel Prize-winning writer, Andrić was well known and respected in his native country during his lifetime.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, beginning in the 1950s and continuing past the breakup of Yugoslavia, his works have been disparaged by Bosniak literary critics for their supposed anti-Muslim bias.

Above: Flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina

In Croatia, his works were long shunned for nationalist reasons, and even briefly blacklisted following Yugoslavia’s dissolution, but were rehabilitated by the literary community at the start of the 21st century.

Above: Flag of Croatia

He is highly regarded in Serbia for his contributions to Serbian literature.

Above: Flag of Serbia

I have aspirations of becoming a published writer and I have always been fascinated by the lives of other writers and how those lives led to the fine literature that these literary legends produced.

In parts one and two of the Author’s Apartment, I wrote of Andric’s life from his birth and childhood to his studies and suffering (1892 -1920).

In 1920, after a time as a civil servant with the Ministry of Religion in Belgrade, Andric was taken into diplomatic service and a new chapter of his life began.

Above: Church of St. Sava, Belgrade

On 20 February 1920, Andrić’s request was granted and he was assigned to the Foreign Ministry’s mission at the Vatican.

Above: Flag of Vatican City

The post of Ambassador was occupied by the famous linguist Lujo Bakotic.

Above: Lujo Bakotic

(Lujo Bakotić (1867 – 1941) was a Serbian writer, publicist, lawyer, lexicographer and diplomat.

Though he was Roman Catholic, Bakotić considered himself Serbian, as had his father.

He completed his high school (gymnasium) education in Split, and jurisprudence in Vienna and Graz.

He was a lawyer by profession who was also politically active, representing the Serbian Party in the Diet of Dalmatia.

Above: Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Dalmatia

Owing to his party’s ideals he had to flee to Serbia in 1913.

With the start of the Great War, he left Belgrade for Niš and then went to Paris and finally Rome, where he was made a secretary in the Vatican to work on a mission, preparing a Concordat between Serbia and the Vatican (which never materialized).

After the war, he was Yugoslavia’s envoy at the Vatican from 1920 until 1923.

Above: St. Peter’s Square, Vatican City

He represented the Kingdom of Yugoslavia at The Hague, and later he was sent by the Serbian government to Moscow.

Above: Kurhaus, The Hague, The Netherlands

He retired as a civil servant in 1935.

Classically educated, Bakotić spoke several languages fluently, including: French, Italian, German, English, Latin and a number of Slavic languages and dialects.)

Above: Lujo Bakotić

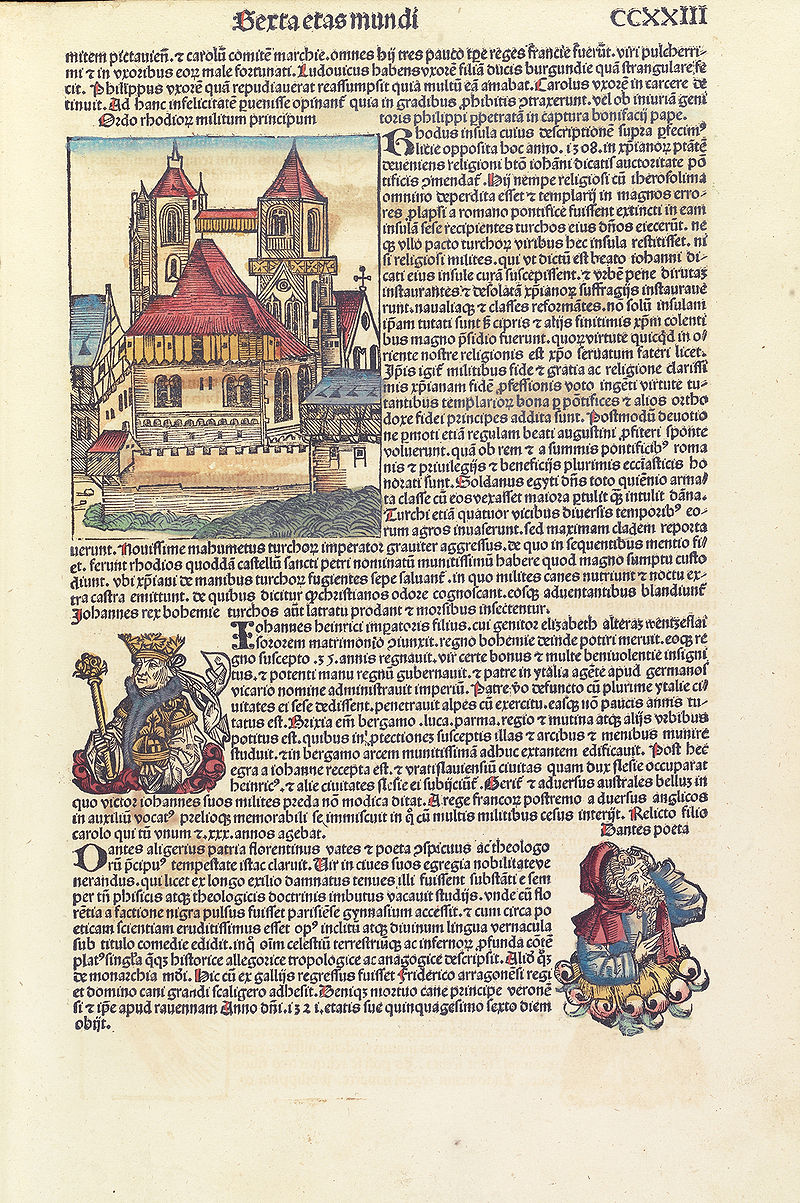

Andric enthusiastically read the works of Francesco Guicciardini.

(Francesco Guicciardini (1483 – 1540) was an Italian historian and statesman.

A friend and critic of Niccolò Machiavelli, he is considered one of the major political writers of the Italian Renaissance.

Above: Niccolò Macchiavelli (1469 – 1527)

In his masterpiece, The History of Italy, Guicciardini paved the way for a new style in historiography with his use of government sources to support arguments and the realistic analysis of the people and events of his time.

The History of Italy stands apart from all his writings because it was the one work which he wrote not for himself, but for the public.

In his research, Guicciardini drew upon material that he gathered from government records as well as from his own extensive experience in politics.

His many personal encounters with powerful Italian rulers serves to explain his perspective as a historian:

“Francesco Guicciardini might be called a psychological historian—for him the motive power of the huge clockwork of events may be traced down the mainspring of individual behavior.

Not any individual, be it noted, but those in positions of command: emperors, princes and popes who may be counted on to act always in terms of their self-interest—the famous Guicciardinian particolare.”

Above: Villa Ravà, Arcetri, the former home of the Guicciardini family, where Francesco Guicciardini wrote The History of Italy

In the following excerpt, the historian records his observations on the character of Pope Clement VII:

“And although he had a most capable intelligence and marvelous knowledge of world affairs, yet he lacked the corresponding resolution and execution.

For he was impeded not only by his timidity of spirit, which was by no means small, and by a strong reluctance to spend, but also by a certain innate irresolution and perplexity, so that he remained almost always in suspension and ambiguous when he was faced with those deciding those thing which from afar he had many times foreseen, considered, and almost revealed.“

Above: Pope Clement VII (né Giulio di Guiliano de’ Medici)(1478 – 1534)

Moreover, what sets Guicciardini apart from other historians of his time is his understanding of historical context.

His approach was already evident in his early work The History of Florence (1509):

“The young historian was already doubtlessly aware of the meaning of historical perspective; the same facts acquiring different weight in different contexts, a sense of proportion was called for.”

Above: Guicciardini Family Crest

In the words of one of Guicciardini’s severest critics, Francesco de Sanctis:

“If we consider intellectual power, the Storia d’Italia is the most important work that has issued from an Italian mind.“)

Above: Francesco de Sanctis (1817 – 1883)

Andric travelled through Tuscany with Milos Crnjanski.

Above: Miloš Crnjanski, 1914

(Miloš Crnjanski (1893 – 1977) was a Serbian writer and poet of the expressionist wing of Serbian modernism, author, and a diplomat.

Crnjanski was born in Csongrád, Hungary, to an impoverished family which moved in 1896 to Temesvár (today Timișoara, Romania).

He completed elementary school in Pančevo and grammar school in Timișoara.

Above: Images of Timisoara, Romania

Then he started attending the Export Academy in Rijeka in 1912, and in the autumn of the following year he started studying in Vienna.

Above: Harbour, Rijeka, Croatia

At the beginning of World War I, Crnjanski was persecuted as part of the general anti-Serbian retribution of Austria to Princip’s assassination in Sarajevo.

Instead of being sent to jail, he was drafted to the Austro-Hungarian Army and sent to the Galician front to fight against the Russians – where he was wounded in 1915.

Crnjanski convalesced in a Vienna war hospital, although just before the end of the war he was sent to the Italian front.

After the war, he graduated in literary studies from the University of Belgrade.

After graduating from the Faculty of Philosophy in 1922, he taught at the Fourth Belgrade Grammar School and espoused “radical modernism” in articles for periodicals including Ideje, Politika and Vreme – sparking “fierce literary and political debates“.

Above: University of Belgrade logo

He entered the diplomatic corps for the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and worked in Germany (1935 – 1938) and Italy (1939 – 1941) before being evacuated during WWII to England.

Above: Flag of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918 – 1941)

He took odd jobs and eventually became the London correspondent of the Argentinian periodical El economist.

During this period he wrote Druga knjiga Seoba (The Second Book on Migration) and Lament nad Beogradom (Lament over Belgrade).

Above. Tower Bridge, London, England

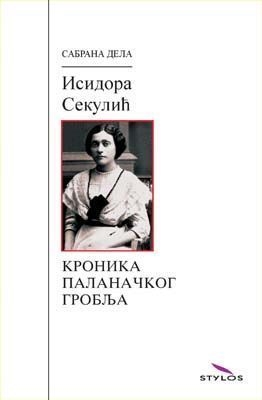

He returned to Belgrade after 20 years of exile in 1965 and shortly after published Sabrana dela u 10 tomova (“Collected works in 10 volumes”).

In 1971, he received the prestigious NIN award for Roman o Londonu.

Above: NIN Award logo

Crnjanski, aged 84, died in Belgrade on 30 November 1977.

He is interred in the Alley of Distinguished Citizens in the Belgrade New Cemetery.

He is considered a classic of Serbian literature by scholars as well as the public.

Crnjanski first books portrayed the futility of war.

He laid the foundations of the early avant-garde movement in Serbian literature, as exemplified by his 1920 Objašnjenje Sumatre (The Explanation of Sumatra):

“The world still hasn’t heard the terrible storm above our heads, while shakings come from beneath, not from political relations, not from literary dogmas, but from life.

Those are the dead reaching out!

They should be avenged.“

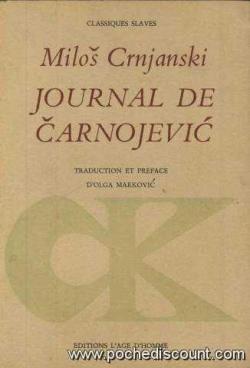

The Journal of Carnojevic is a lyrical novel by Miloš Crnjanski, which was first published in 1920.

The narrator of the novel is Petar Rajic, who tells his story in which there is no clearly established narrative flow, nor are events connected by cause and effect.

The protagonist of the book is a young Serbian soldier who lived in Vojvodina, now northern Serbia, which was, at the time, a part of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

When WW I began, he was, along with thousands of other young Serbs, recruited to the Austro-Hungarian army, and the war completely obliterated his image of the world.

Crnjanski himself had such a destiny, and he wrote the book right after coming back from the war – still as a young man.

The book is a combination of the present, the past and the future, strangely intertwined.

We can’t even say who he is – because of his alter ego, the sailor.

Just like the borders between the periods of life, the borders between persons are blurred and unclear.

“Autumn, and life without meaning.

I drag myself around taverns.

I sit by the window and stare at the mist and the yellow, wet, scarlet trees.

And where is life?”

“All they were doing, he said that somewhere, far away, on some island, was leaving a mark.

And when he would tell her that now, from her passionate smile, a red plant on Ceylon Island is drawing its strength to open, she would gaze at the distance.

She didn’t believe that all our actions could reach that far and that our power is so endless.

And that was the last thing he believed in.

Under the palm trees, in the hotel lobby, he told her that he didn’t believe someone could be killed, nor made unhappy.

He didn’t believe in the future.

He said his fleshly passions depended solely upon the color of the sky, and that life is being lived in vain – no, not in vain, but for the sake of a smile, with which he smiles to both plants and clouds.

He said that all his actions depended on some scarlet trees that he had seen on Ios Island.

She giggled.

Ah, he was funny and young.

So young.”

“I will go past borders and cities and villages and forests and waters and there will be nothing left on me but dust on my feet, silence in my heart and on my face a mild smile meaningless and burning.

So many are the places where something had been left, ripped out of my torn apart soul and my ragged life.“)

Above: Portrait of Milos Crnjanski

Andrić left Belgrade soon after, and reported for duty in late February.

At this time, he published his first short story, Put Alije Đerzeleza (The Journey of Alija Đerzelez).

(Gjergj Elez Alia or Đerzelez Alija is a popular legendary hero in epic poetry and literature in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Gora and in northern Albania.

Muslims from Bosnian Krajina modeled the poetic image of Alija Đerzelez after the image of Serbian (Christian) Prince Marko, based on the historic person Ali Bey Mihaloğlu.

Marko Mrnjavčević (1335 – 1395) was the de jure Serbian king from 1371 to 1395, while he was the de facto ruler of territory in western Macedonia centered on the town of Prilep.

He is known as Prince Marko and King Marko in South Slavic oral tradition, in which he has become a major character during the period of Ottoman rule over the Balkans.

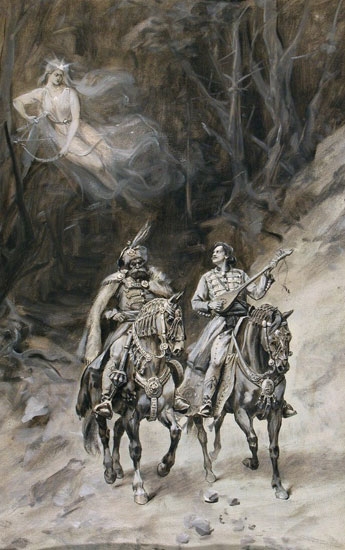

Above: Portrait of Prince Marko

Marko’s father, King Vukašin, was co-ruler with Serbian Tsar Stefan Uroš V, whose reign was characterised by weakening central authority and the gradual disintegration of the Serbian Empire.

Vukašin’s holdings included lands in western Macedonia and Kosovo.

Above: King Vukasin

In 1370, he crowned Marko “young king“:

This title included the possibility that Marko would succeed the childless Uroš on the Serbian throne.

Above: Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Serbia

On 26 September 1371, Vukašin was killed and his forces defeated in the Battle of Maritsa.

About two months later, Tsar Uroš died.

This formally made Marko King of Serbia.

Above: Maritsa Valley

However, Serbian noblemen, who had become effectively independent from the central authority, did not even consider to recognise him as their supreme ruler.

Sometime after 1371, he became an Ottoman vassal.

Above: Ottoman Empire logo

By 1377, significant portions of the territory he inherited from Vukašin were seized by other noblemen.

King Marko, in reality, came to be a regional lord who ruled over a relatively small territory in western Macedonia.

He funded the construction of the Monastery of Saint Demetrius near Skopje (better known as Marko’s Monastery), which was completed in 1376.

Above: Marko’s Monastery

Marko died on 17 May 1395, fighting for the Ottomans against the Wallachians in the Battle of Rovine.

Above: Battle of Rovine

Although a ruler of modest historical significance, Marko became a major character in South Slavic oral tradition.

He is venerated as a national hero by the Serbs, Macedonians and Bulgarians, remembered in Balkan folklore as a fearless and powerful protector of the weak, who fought against injustice and confronted the Turks during the Ottoman occupation.

Above: A Herzegovinian sings with a gusle in an 1823 drawing.

Serbian epic poems were often sung, accompanied by this traditional instrument.

South Slavic legends about Kraljević Marko or Krali Marko are primarily based on myths much older than the historical Marko Mrnjavčević.

He differs in legend from the folk poems:

In some areas he was imagined as a giant who walked stepping on hilltops, his head touching the clouds.

He was said to have helped God shape the Earth, and created the river gorge in Demir Kapija (“Iron Gate“) with a stroke of his sabre.

This drained the sea covering the regions of Bitola, Mariovo and Tikveš in Macedonia, making them habitable.

Above: Demir Kapija

After the Earth was shaped, Marko arrogantly showed off his strength.

God took it away by leaving a bag as heavy as the Earth on a road.

When Marko tried to lift it, he lost his strength and became an ordinary man.

Legend also has it that Marko acquired his strength after he was suckled by a vila.

King Vukašin threw him into a river because he did not resemble him, but the boy was saved by a cowherd (who adopted him, and a vila suckled him).

Above: Serbian epic heroes Prince Marko and Miloš Obilić, and the vila Ravijojla

In other accounts, Marko was a shepherd (or cowherd) who found a vila‘s children lost in a mountain and shaded them against the sun (or gave them water).

As a reward the vila suckled him three times, and he could lift and throw a large boulder.

An Istrian version has Marko making a shade for two snakes, instead of the children.

In a Bulgarian version, each of the three draughts of milk he suckled from the vila‘s breast became a snake.

Marko was associated with large, solitary boulders and indentations in rocks:

The boulders were said to be thrown by him from a hill, and the indentations were his footprints (or the hoofprints of his horse).

He was also connected with geographic features such as hills, glens, cliffs, caves, rivers, brooks and groves, which he created or at which he did something memorable.

They were often named after him, and there are many toponyms (place names) — from Istria in the west to Bulgaria in the east — derived from his name.

In Bulgarian and Macedonian stories, Marko had an equally strong sister who competed with him in throwing boulders.

In some legends, Marko’s wonder horse was a gift from a vila (a mountain nymph).

A Serbian story says that he was looking for a horse who could bear him.

To test a steed, he would grab him by the tail and sling him over his shoulder.

Seeing a diseased piebald foal owned by some carters, Marko grabbed him by the tail but could not move him.

He bought (and cured) the foal, naming him Šarac.

He became an enormously powerful horse and Marko’s inseparable companion.

Macedonian legend has it that Marko, following a vila‘s advice, captured a sick horse on a mountain and cured him.

Crusted patches on the horse’s skin grew white hairs, and he became a piebald.

According to folk tradition Marko never died:

He lives on in a cave, in a moss-covered den or in an unknown land.

A Serbian legend recounts that Marko once fought a battle in which so many men were killed that the soldiers (and their horses) swam in blood.

He lifted his hands towards heaven and said:

“Oh God, what am I going to do now?”

God took pity on Marko, transporting him and Šarac to a cave (where Marko stuck his sabre into a rock and fell asleep).

There is moss in the cave.

Šarac eats it bit by bit, while the sabre slowly emerges from the rock.

When it falls on the ground and Šarac finishes the moss, Marko will awaken and reenter the world.

Some allegedly saw him after descending into a deep pit, where he lived in a large house in front of which Šarac was seen.

Others saw him in a faraway land, living in a cave.

According to Macedonian tradition Marko drank “eagle’s water“, which made him immortal.

He is with Elijah in heaven.

Mihaloğlu Ali Bey or Gazı Alauddin Mihaloğlu Ali Bey, (1425—1507) was an Ottoman military commander in the 15th century and the first sanjakbey (provincial governor) of the Sanjak of Smederevo (the territory of Belgrade).

He was one of the descendants of Köse Mihal, a Byzantine governor of Chirmenkia and battle companion of Osman Gazi.

I am not certain of why Ali Bey is so honoured, for it seems he was continuously defeated in almost every military campaign he was involved in.

Songs about Đerzelez Alija were transmitted by bilingual singers from South Slavic milieu to northern Albanian milieu, where he is known as Gjergj Elez Alia.)

The year 1920 was a year of great changes:

- the First Red Scare, a widespread fear of far left extremism in the United States, continues, as do the Palmer (after Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer) Raids: on one day alone (2 January) 4,025 people were arrested in several cities across the country – mostly Italian and Jewish immigrants were targeted.

- the Russian Civil War still raged

- the League of Nations began sessions in Paris before moving to Geneva

- the Netherlands refused to extradite exiled German Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859 – 1941)

- Prohibition in the United States began

- the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) was founded and women’s suffragism realized in the US

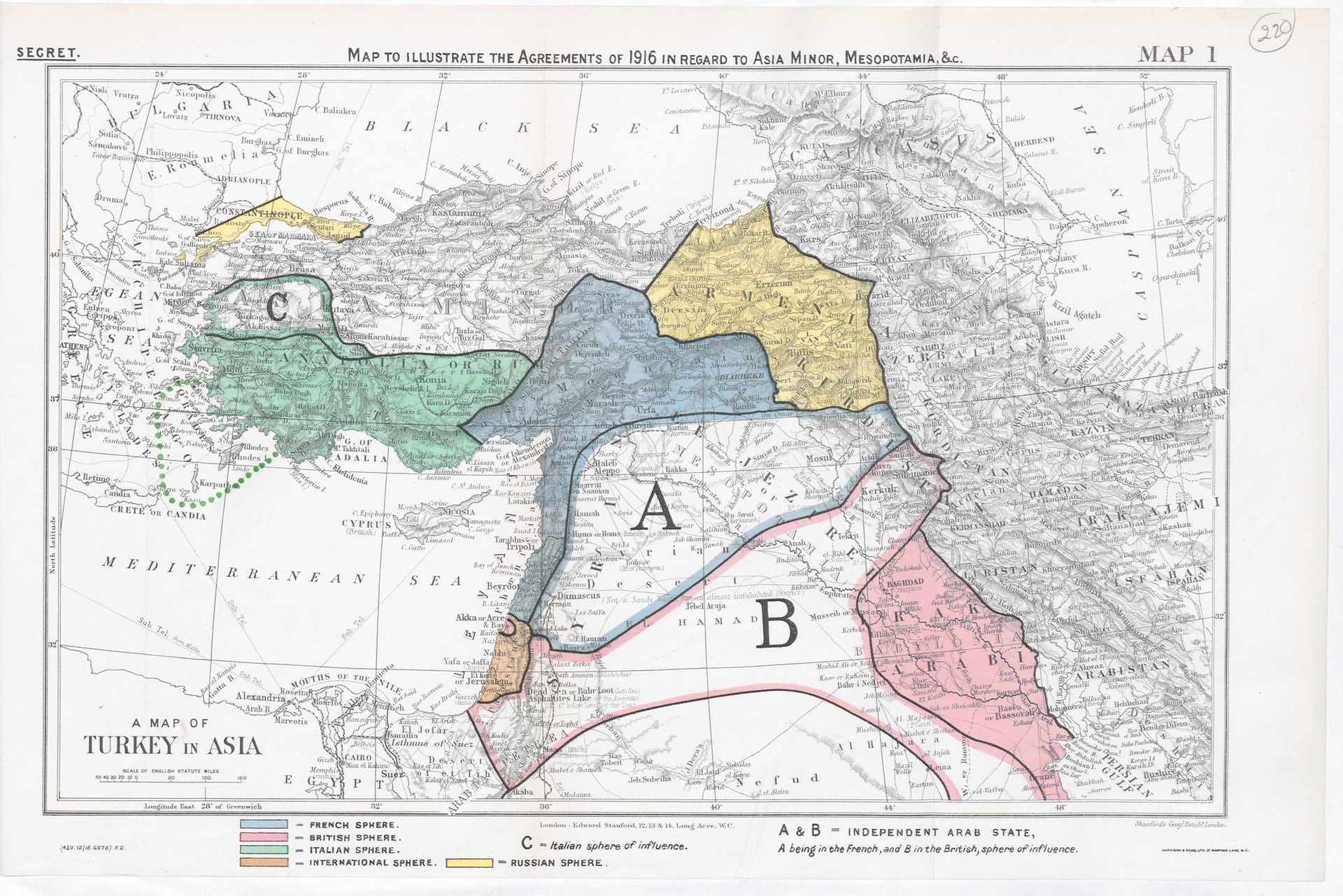

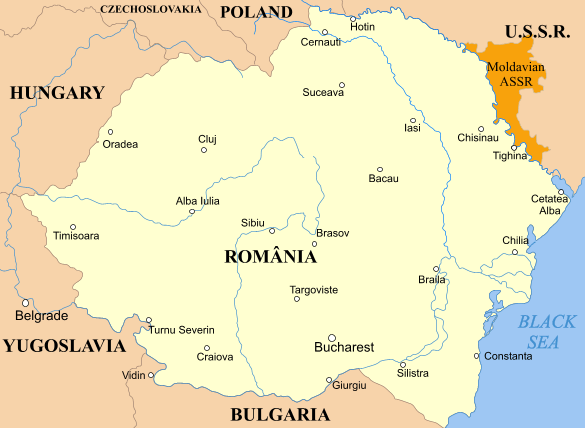

- the victorious Allies carved up the former Ottoman Empire and Hungary lost 72% of its pre-WW1 territory

Above: The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, by Sir William Orpen

- the German Workers Party renamed itself the Nazi Party

- Estonia, Lithuania and Syria all gain their independence this year

Above: Flag of Estonia

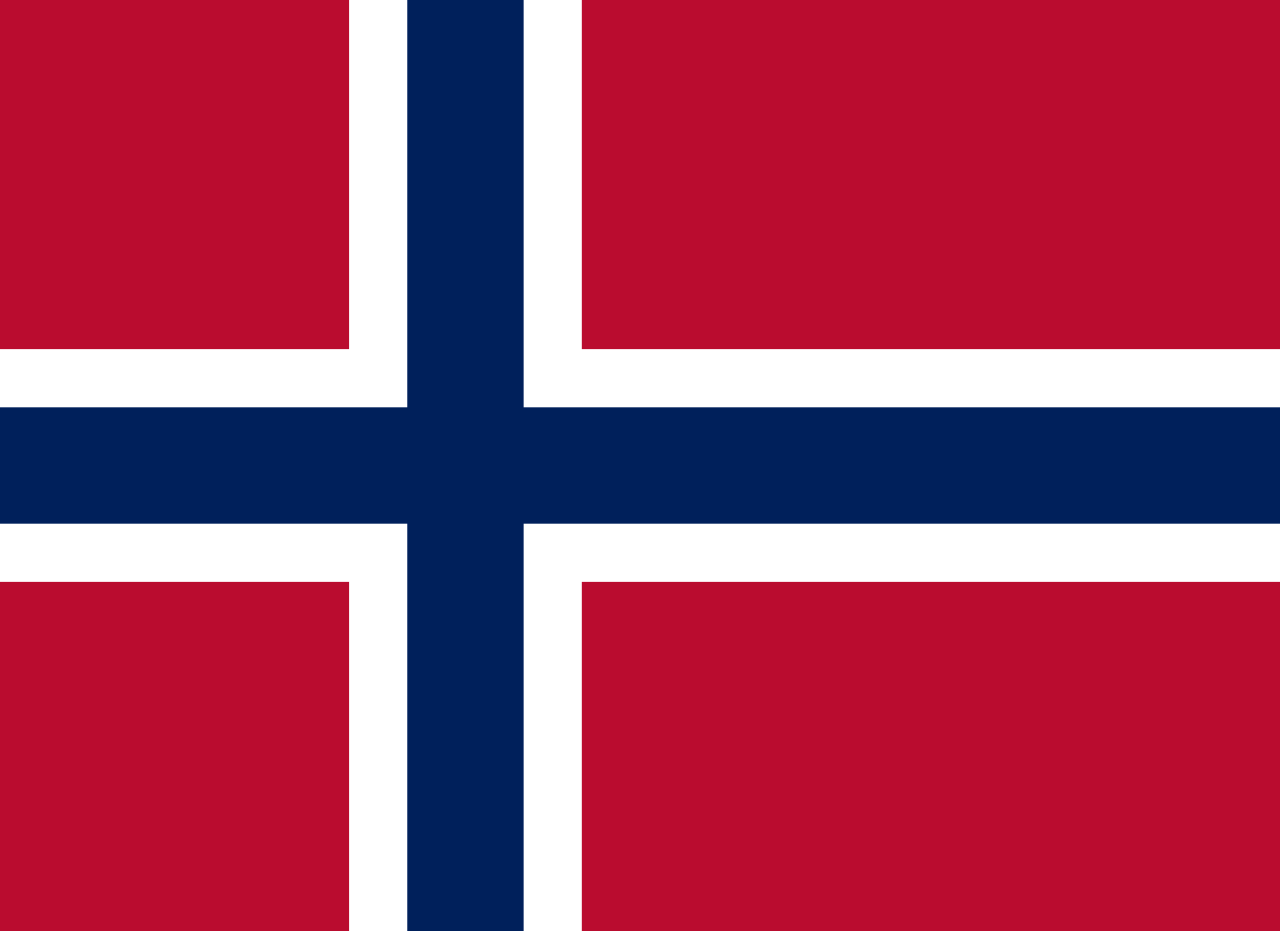

- the world’s first peaceful establishment of a social democratic government took place in Sweden

- the US Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles claiming that it was too harsh on the defeated participants of WW1

- the Summer Olympics opened in Antwerp, Belgium

- the Mexican Revolution ended

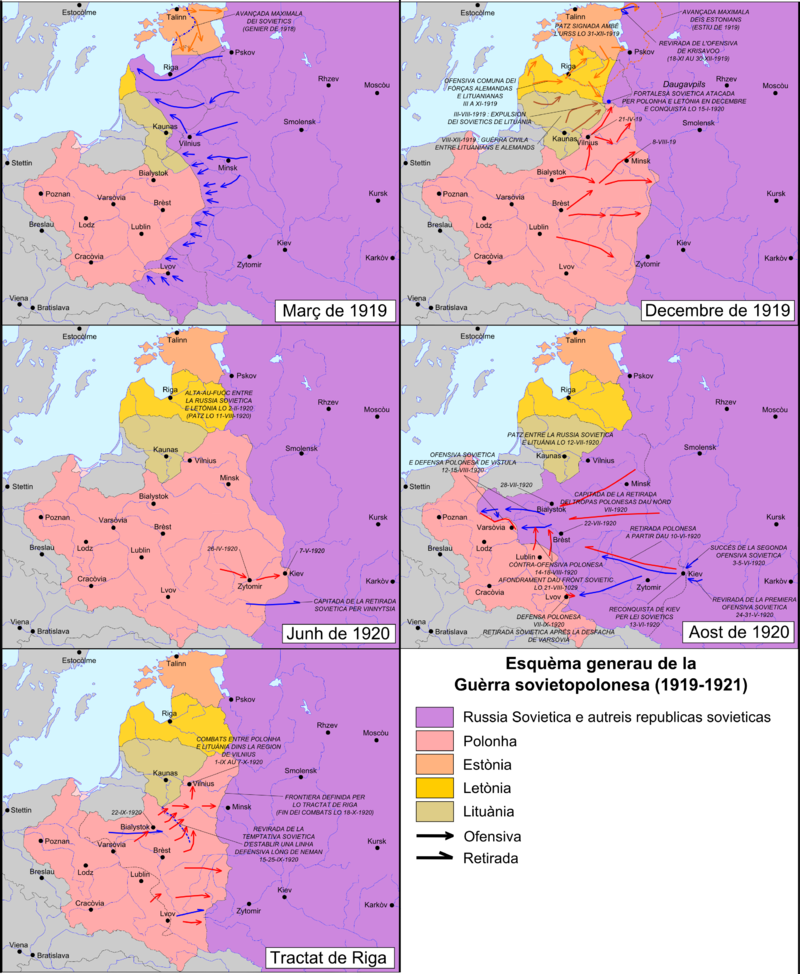

- the Polish – Russian War ended in a Polish victory

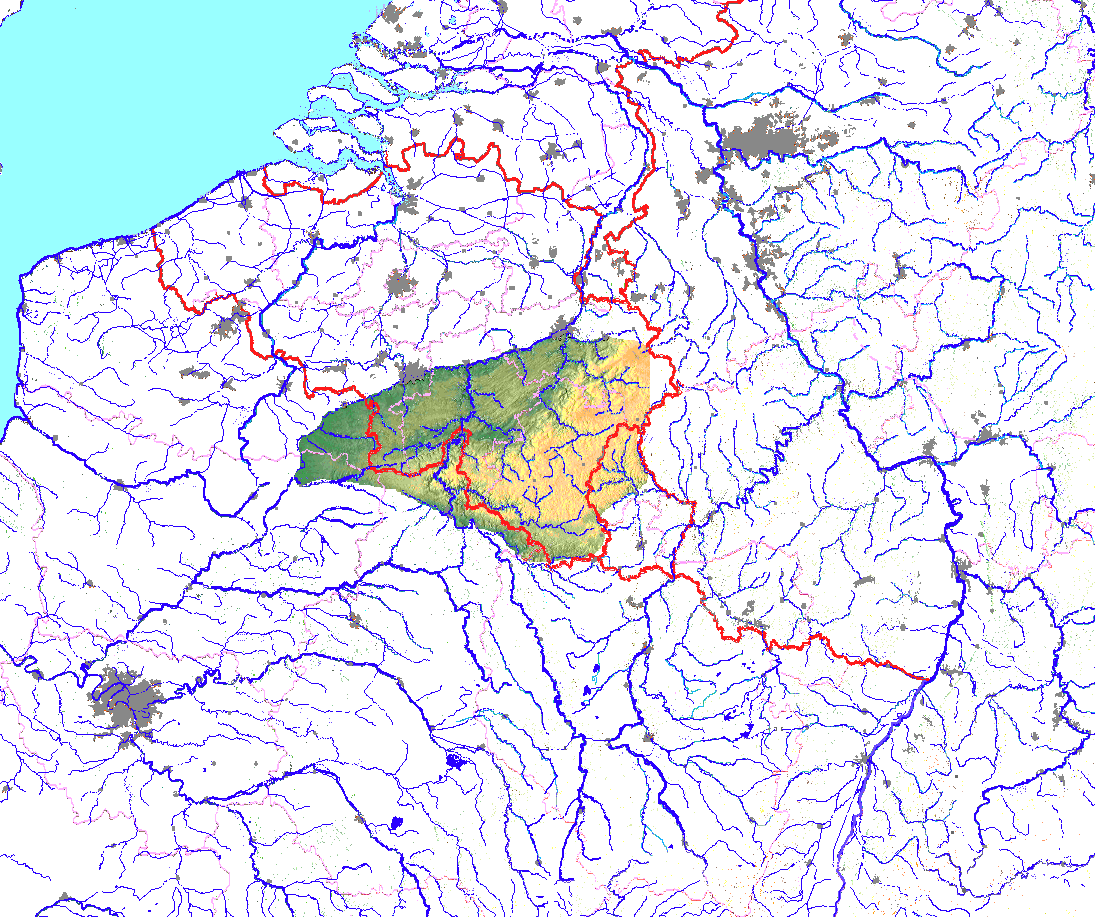

Above: Five stages of the Polish-Soviet War

- Albanian PM Essad Pasha Toptani (1863 – 1920) was assassinated in Paris

- the US Postal Service ruled that children cannot be mailed

- three African American circus workers were lynched in Duluth, Minnesota

- Arthur Meighen (1874 – 1960) became the 9th Prime Minister of Canada

- the Irish War of Independence still raged, including “Bloody Sunday“

- the HIV / AIDS pandemic began in Léopoldville (today’s Kinshasa)

With the end of World War I and the collapse of both the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires the conditions were met for proclaiming the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in December 1918.

The Yugoslav ideal had long been cultivated by the intellectual circles of the three nations that gave the name to the country, but the international constellation of political forces and interests did not permit its implementation until then.

However, after the war, idealist intellectuals gave way to politicians, and the most influential Croatian politicians opposed the new state right from the start.

It was not certain through much of 1920 whether the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Yugoslavia) would survive its own internal divisions.

Above: Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

As for the Vatican, the Roman Question was still unresolved.

On 9 February 1849, the Roman Republic took over the government of the Papal States.

In the following July, an intervention by French troops restored Pope Pius IX to power, making the Roman Question a hotly debated one even in the internal politics of France.

In July 1859, after France and Austria made an agreement that ended the short Second Italian War of Independence, an article headed “The Roman Question” in the Westminster Review expressed the opinion that the Papal States should be deprived of the Adriatic provinces and be restricted to the territory around Rome.

This became a reality in the following year, when most of the Papal States were annexed by what became the Kingdom of Italy.

Above: the Italian peninsula, 1796

The Vatican is the religious centre of Catholicism, but the question raged as to whether it should also continue to have its own territory.

This question was not resolved until 1929.

Above: Coat of arms of the Bishop of Rome (aka the Pope)

In the midst of all this, Andric began his diplomatic career.

Andric complained that the consulate was understaffed and that he did not have enough time to write.

All evidence suggests he had a strong distaste for the ceremony and pomp that accompanied his work in the diplomatic service, but according to Hawkesworth, he endured it with “dignified good grace“.

Around this time, he began writing in the Ekavian dialect used in Serbia, and ceased writing in the Ijekavian dialect used in his native Bosnia.

Andrić soon requested another assignment.

In November, he was transferred to Bucharest.

Once again, his health deteriorated.

Nevertheless, Andrić found his consular duties there did not require much effort, so he focused on writing, contributed articles to a Romanian journal and even had time to visit his family in Bosnia.

Above: Flag of Romania

The Treaty of Bucharest was signed between Romania and the Entente Powers on 17 August 1916 in Bucharest.

The treaty stipulated the conditions under which Romania agreed to join the war on the side of the Entente, particularly territorial promises in Austria-Hungary.

The signatories bound themselves to keep secret the contents of the treaty until a general peace was concluded.

Above: Treaty of Bucharest

Romanians!

The war which for the last two years has been encircling our frontiers more and more closely has shaken the ancient foundations of Europe to their depths.

It has brought the day which has been awaited for centuries by the national conscience, by the founders of the Romanian State, by those who united the principalities in the war of independence, by those responsible for the national renaissance.

It is the day of the union of all branches of our nation.

Today we are able to complete the task of our forefathers and to establish forever that which Michael the Great was only able to establish for a moment, namely, a Romanian union on both slopes of the Carpathians.

For us the mountains and plains of Bukowina, where Stephen the Great has slept for centuries.

In our moral energy and our valour lie the means of giving him back his birthright of a great and free Rumania from the Tisza to the Black Sea, and to prosper in peace in accordance with our customs and our hopes and dreams.

Part of the proclamation by King Ferdinand, 28 August 1916

Above: King Ferdinand I of Romania (1865 – 1927)

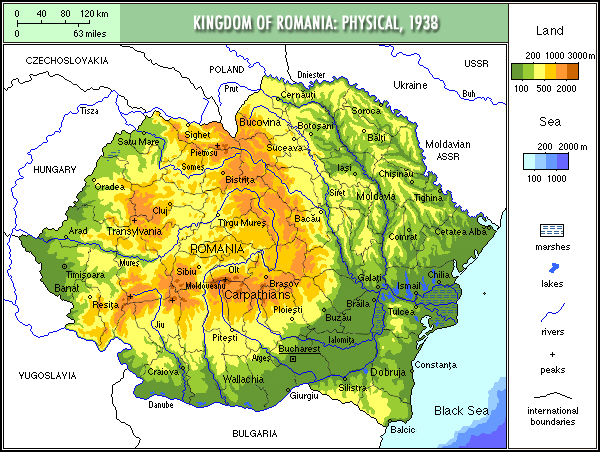

The concept of “Greater Romania“ materialized as a geopolitical reality after the First World War.

Romania gained control over Bessarabia, Bukovina and Transylvania.

As a result, most regions with clear Romanian majorities were merged into a single state.

It also led to the inclusion of sizable minorities, including Magyars (ethnic Hungarians), Germans, Jews, Ukrainians and Bulgarians — about 28% of the country’s population.

The borders established by the treaties concluding the war did not change until 1940.

The resulting state, often referred to as “România Mare” or România Întregită (roughly translated in English as “Romania Made Whole“), was seen as the ‘true’, whole Romanian state, or, as Tom Gallagher states, the “Holy Grail of Romanian nationalism“.

The Romanian ideology changed due to the demographic, cultural and social alterations, however the nationalist desire for a homogeneous Romanian state conflicted with the multiethnic, multicultural truth of Greater Romania.

From 1918 to 1938, Romania was a monarchy whose liberal Constitution was seldom respected in practice.

Above: Greater Romania (1920 – 1940)

In 1922, Andrić requested another reassignment.

He was transferred to the consulate in Trieste, where he arrived on 9 December 1922.

Above: Flag of Trieste

At the beginning of the 20th century, Trieste was a bustling cosmopolitan city frequented by artists and philosophers such as James Joyce, Italo Svevo, Sigmund Freud, Zofka Kveder, Dragotin Kette, Ivan Cankar, Scipio Slataper, and Umberto Saba.

The city was the major port on the Austrian Riviera, and perhaps the only real enclave of Mitteleuropa (i.e., Central Europe) on the Mediterranean.

Viennese architecture and coffeehouses dominate the streets of Trieste to this day.

Above: Images of Trieste

Italy, in return for entering World War I on the side of the Allied Powers, had been promised substantial territorial gains, which included the former Austrian Littoral and western Inner Carniola.

Italy therefore annexed the city of Trieste at the end of the war, in accordance with the provisions of the 1915 Treaty of London and the Italian-Yugoslav 1920 Treaty of Rapallo.

Above: Flag of the Kingdom of Italy (1861 – 1946)

The Treaty of Rapallo was a treaty between the Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (renamed Yugoslavia in 1929), signed to solve the dispute over some territories in the former Austrian Littoral in the upper Adriatic and in Dalmatia.

The treaty was signed on 12 November 1920 in Rapallo, near Genoa, Italy.

Above: Rapallo

Tension between Italy and Yugoslavia arose at the end of World War I, when the Austro-Hungarian Empire dissolved and Italy claimed the territories assigned to it by the secret Treaty of London of 1915.

According to the treaty signed in London on 26 April 1915 by the Kingdom of Italy and the Triple Entente, in case of victory at the end of World War I, Italy was to obtain several territorial gains including former Austrian Littoral, northern Dalmatia and notably Zadar, Šibenik, and most of the Dalmatian islands (except Krk and Rab).

These territories had an ethnically mixed population, with Slovenes and Croats composing over the half of the population of the region.

The treaty was therefore nullified with the Treaty of Versailles under pressure of President Woodrow Wilson, making void Italian claims on northern Dalmatia.

The objective of the Treaty of Rapallo was to find a compromise following the void created by the non-application of the Treaty of London of 1915.

While only a few thousands Italians remained in the newly established South Slavic state, a population of half a million Slavs, including the annexed Slovenes, were cut off from the remaining three-quarters of total Slovene population at the time and were subjected to forced Italianization.

Trieste had a large Italian majority, but it had more ethnic Slovene inhabitants than even Slovenia’s capital of Ljubljana at the end of 19th century.

Andric’s Trieste assignment meant he was representing Slovenes in a predominantly Slovene-populated territory now under Italian control.

Above: Peter Kozler’s map of the Slovene Lands, designed during the Spring of Nations in 1848, became the symbol of the quest for a United Slovenia.

The Italian lower middle class—who felt most threatened by the city’s Slovene middle class—sought to make Trieste a città italianissima, committing a series of attacks led by the Black Shirts against Slovene-owned shops, libraries, and lawyers’ offices, even burning down the Trieste National Hall, a central building to the Slovene community.

On 13 July 1920, the building was burned by the Fascist Blackshirts, led by Francesco Giunta.

The act was praised by Benito Mussolini, who had not yet assumed power, as a “masterpiece of the Triestine Fascism“.

It was part of a wider pogrom against the Slovenes and other Slavs in the very centre of Trieste and the harbinger of the ensuing violence against Slovenes and Croats.

Above: Fascist logo

By the mid-1930s several thousand Slovenes, especially members of the middle class and the intelligentsia from Trieste, emigrated to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia or to South America.

Among the notable Slovene émigrés from Trieste were the author Vladimir Bartol, the legal theorist Boris Furlan and the Argentine architect Viktor Sulčič.

The political leadership of the around 70,000 émigrés from the Julian March in Yugoslavia was mostly composed of Trieste Slovenes: Lavo Čermelj, Josip Vilfan and Ivan Marija Čok.

Above: Flag of modern Slovenia

In 1926, claiming that it was restoring surnames to their original Italian form, the Italian government announced the Italianization of German, Slovene and Croatian surnames.

In the Province of Trieste alone, 3,000 surnames were modified and 60,000 people had their surnames amended to an Italian-sounding form.

The psychological trauma, experienced by more than 150,000 people, led to a massive emigration of German and Slavic families from Trieste.

Despite the exodus of the Slovene and German speakers, the city’s population increased because of the migration of Italians from other parts of Italy.

Several thousand ethnic Italians from Dalmatia also moved to Trieste from the newly created Yugoslavia.

The city’s damp climate only caused Andrić’s health to deteriorate further.

On his doctor’s advice, he transferred to Graz in January 1923.

Above: Hauptplatz, Graz, Austria

Graz is the capital city of Styria and second-largest city in Austria after Vienna.

Above: Graz

Emerging from the war, Austria had two main political parties on the right and one on the left.

Above: Flag of Austria

The right was split between clericalism and nationalism.

The Christian Social Party, (Christlichsoziale Partei, CS), had been founded in 1891 and achieved plurality from 1907–1911 before losing it to the socialists.

Their influence had been waning in the capital, even before 1914, but became the dominant party of the First Republic, and the party of government from 1920 onwards.

The CS had close ties to the Roman Catholic Church and was headed by a Catholic priest named Ignaz Seipel (1876–1932), who served twice as Chancellor (1922–1924 / 1926–1929).

While in power, Seipel was working for an alliance between wealthy industrialists and the Roman Catholic Church.

The CS drew its political support from conservative rural Catholics.

In 1920 the Greater German People’s Party (Großdeutsche Volkspartei, GDVP) was founded from the bulk of liberal and national groups and became the junior partner of the CS.

On the left the Social Democratic Workers’ Party of Austria (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Österreichs, SDAPÖ) founded in 1898, which pursued a fairly left-wing course known as Austromarxism at that time, could count on a secure majority in “Red Vienna” (as the capital was known from 1918 to 1934), while right-wing parties controlled all other states.

The SDAPÖ were the strongest voting bloc from 1911 to 1918.

Between 1918 and 1920, there was a grand coalition government including both left and right-wing parties, the CS and the Social Democratic Workers’ Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Österreichs, SDAPÖ).

This gave the Social Democrats their first opportunity to influence Austrian politics.

The coalition enacted progressive socio-economic and labour legislation, such as the vote for women on 27 November 1918, but collapsed on 22 October 1920.

In 1920, the modern Constitution of Austria was enacted, but from 1920 onwards Austrian politics were characterized by intense and sometimes violent conflict between left and right.

The bourgeois parties maintained their dominance but formed unstable governments while socialists remained the largest elected party numerically.

Both right-wing and left-wing paramilitary forces were created during the 20s.

The Heimwehr (Home Resistance) first appeared on 12 May 1920 and became progressively organised over the next three years and the Republikanischer Schutzbund was formed in response to this on 19 February 1923.

From 2 April 1923 to 30 September there were violent clashes between Socialists and Nazis in Vienna.

On 2 April, referred to as Schlacht auf dem Exelberg (Battle of Exelberg) involved 300 Nazis against 90 Socialists.

Further episodes occurred on 4 May and 30 September 1923.

A clash between those groups in Schattendorf, Burgenland, on 30 January 1927, led to the death of a man and a child.

Above: Schattendorf

Right-wing veterans were indicted at a court in Vienna, but acquitted in a jury trial.

This led to massive protests and a fire at the Justizpalast (Palace of Justice) in Vienna.

In the July Revolt of 1927, 89 protesters were killed by the Austrian police forces.

Political conflict escalated until the early 1930s.

Above: the Palace of Justice, Vienna, before the fire

Whether the violence that Vienna viewed was reflected in Graz was never recorded by Andric during his time there as both vice-consul and student.

Andric arrived in the city on 23 January 1923 and was appointed vice-consul.

Andrić soon enrolled at the University of Graz, resumed his schooling and began working on his doctoral dissertation in Slavic studies.

Above: University of Graz logo

In August 1923, Andrić experienced an unexpected career setback.

A law had been passed stipulating that all civil servants had to have a doctoral degree.

As Andrić had not completed his dissertation, he was informed that his employment would be terminated.

Andrić’s well-connected friends intervened on his behalf and appealed to Foreign Minister Momčilo Ninčić, citing Andrić’s diplomatic and linguistic abilities.

Above: Momčilo Ninčić (1876 – 1949), Serbian politician and economist, and president of the League of Nations (1926 – 1927)

In February 1924, the Foreign Ministry decided to retain Andrić as a day worker with the salary of a vice-consul.

This gave him the opportunity to complete his Ph.D.

Three months later, on 24 May, Andrić submitted his dissertation to a committee of examiners at the University of Graz, who gave it their approval.

This allowed Andrić to take the examinations necessary for his Ph.D to be confirmed.

He passed both his exams, and on 13 July, received his Ph.D.

The committee of examiners recommended that Andrić’s dissertation be published.

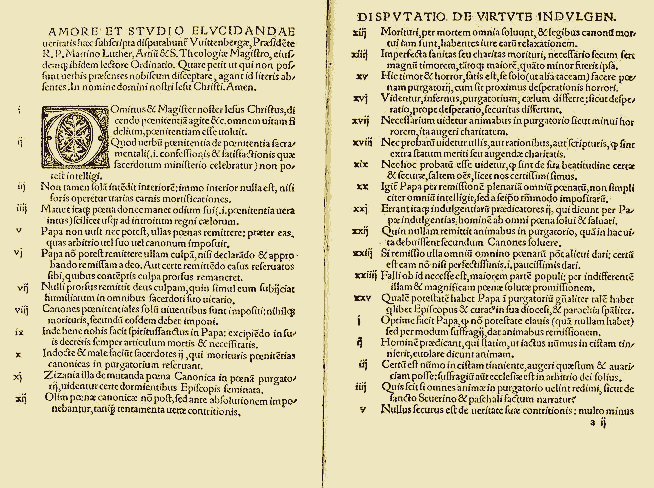

Andrić chose the title Die Entwicklung des geistigen Lebens in Bosnien unter der Einwirkung der türkischen Herrschaft (The Development of Spiritual Life in Bosnia Under the Influence of Turkish Rule).

In it, he characterized the Ottoman occupation as a yoke that still loomed over Bosnia.

“The effect of Turkish rule was absolutely negative,” he wrote.

“The Turks could bring no cultural content or sense of higher mission, even to those South Slavs who accepted Islam.“

Several days after receiving his Ph.D, Andrić wrote the Foreign Minister asking to be reinstated and submitted a copy of his dissertation, university documents and a medical certification that deemed him to be in good health.

In September, the Foreign Ministry granted his request.

Above: Bust of Ivo Andric, Graz

Andrić stayed in Graz until 31 October 1924, when he was assigned to the Foreign Ministry’s Belgrade headquarters.

During the two years he was in Belgrade, Andrić spent much of his time writing.

His first collection of short stories was published in 1924, and he received a prize from the Serbian Royal Academy (of which he became a full-fledged member in February 1926).

Above: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts plaque

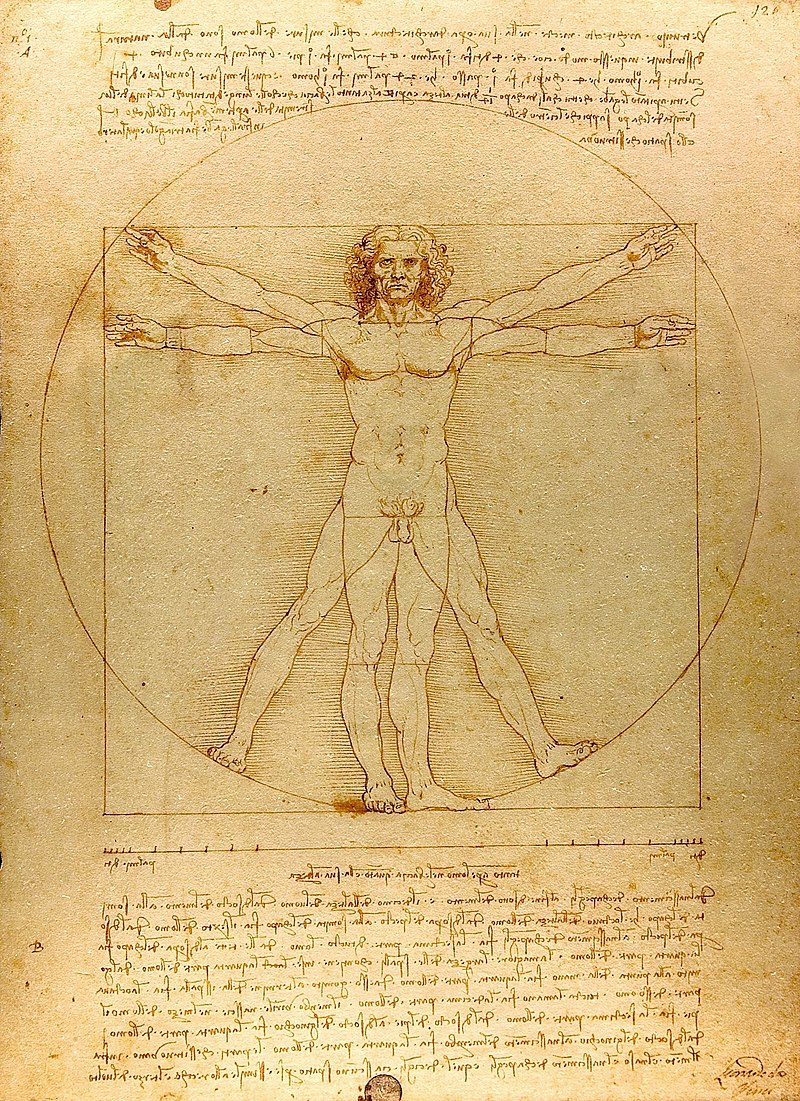

The reader who takes the collected works of one writer, reads them as a connected whole, despite all the contradictions and breaks that the work of one writer carries within itself.

He passes through that work as through a well-arranged street in which the facades of houses are interconnected, and everything comes to him as one more or less planned and well-connected whole.

Because such a reader stands at the end point of the writer’s work, looks in the opposite direction from the one in which those works were created, observes them as a whole and continuity that they could not have when, one by one, they were slowly and difficultly created in long and restless periods of life.

Ivo Andrić

Signs by the Roadside

And what is, basically, a story?

How, in the shortest outline, could a story be described rather than precisely defined?

One of the most important features of the story is its size, ie the measure of its conciseness.

It depends on the extent of the compression of the form how the writer will arrange his material, how he will construct the plot and how to introduce his theme into it or network more motives, how he will explain his linguistic potential.

There is no doubt that the narrative is based on the categories of selection and summarization, on giving a restrictive, reduced form to the process of narration.

The concentration of attention, conciseness and interestingness of the narration must be in the foreground in order to achieve the impression of a unique whole.

That is why the story relies on a “limited world“, on a clearly emphasized detail, a motivated situation or an emphasized character.

But, the core, the essence, the justification of the existence of every story cannot be reduced only to its formal characteristics, because the most important thing is the story, the process of telling, the narration.

It gives meaning to human existence and its torment to reach the meaning and reason for the existence of the world.

From time immemorial, humanity has been telling stories, stories about heroism, love, suffering, betrayal, loyalty and friendship, the story is inherent in man, an integral part of his position in an interactive relationship with the world.

And it is no coincidence that Andrić put the words of his “uncle“, the late Fr. Rafa, into the mouth of his hero, Fr. Petar, who always joked:

“I could still do without bread, but without talking I can’t.“

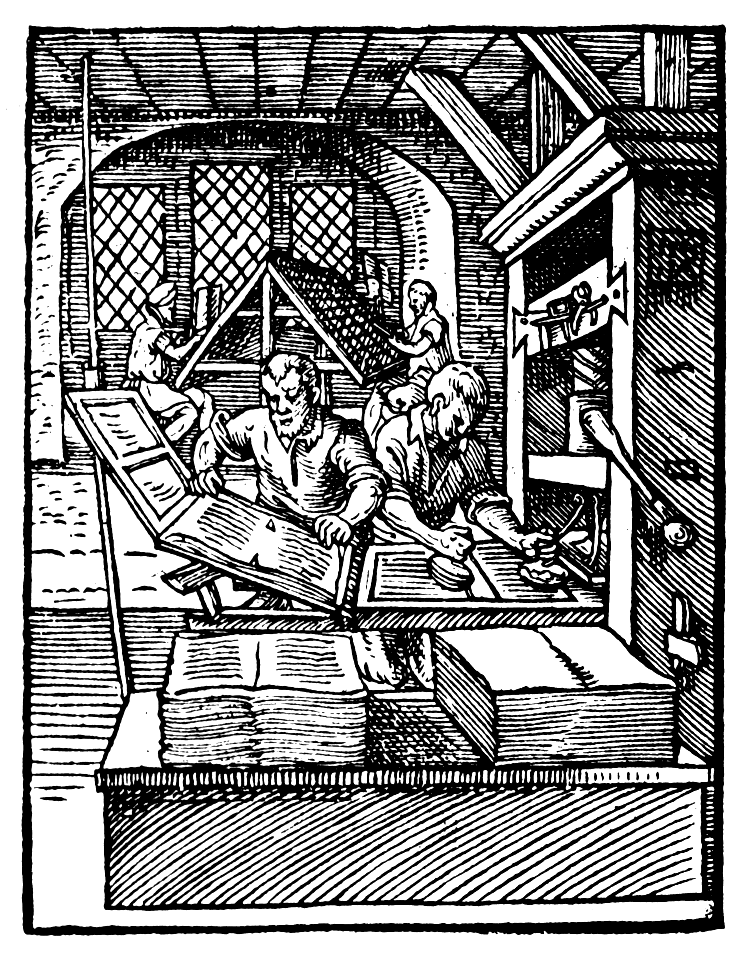

In a thousand different languages, in various living conditions, from century to century, from ancient patriarchal stories in huts, by the fire, to modern narrators who are coming out of publishing houses in major world centers at the moment, the story of human destiny is being told, which people tell people without end and interruption.

The way and forms of that story change over time and circumstances, but the need for storytelling and storytelling remains, and the story flows on and the storytelling has no end.

So sometimes it seems to us that humanity, from the first flash of consciousness, through the centuries, tells itself, in a million variants, along with the breath of its lungs and the rhythm of its being, constantly the same story.

And that story seems to want, like the story of the legendary Scheherazade, to deceive the executioner, to postpone the inevitability of the tragic accident that threatens us, and to prolong the illusion of life and duration.

Above: Scheherazade, painted in the 19th century by Sophie Anderson

Perhaps the goal of that story is to light up, at least a little, the dark paths that life often throws us on, and to tell us something more about that life, which we live but which we do not always see and understand, than we, in our weakness, can know and understand.

Often only from the words of a good narrator do we learn what we have done and what we have missed, what we should do and what we should not.

Perhaps these stories, oral and written, also contain the true history of mankind, and perhaps one could at least sense, if not find out, the meaning of that history.

And that regardless of whether they are dealing with the past or the present.

Perhaps one could at least infer from them, if not find out, the meaning of that history.

Above: History by Frederick Dielman (1896)

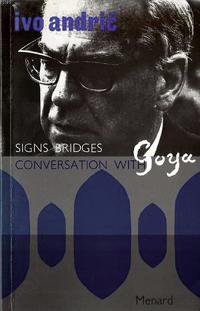

Andrić in his imaginary “Conversation with Goya” in 1935, Andrić’s hero Goja, the narrator’s interlocutor, sees life and story as creatively intertwined.

Because without a story there is no real life.

And how to get to the story, that key to everything that “happened and is happening“, which is repeated in countless different forms?

Legends should be listened to:

“Those traces of collective human efforts through the centuries and the meaning of our destiny should be deciphered from them as much as possible”, says Andrićev Goja in one place, and further adds that the meaning should be sought “in those layers of humanity. ”

In 1924, the same year when he defended his doctoral dissertation in Graz, The Development of Spiritual Life in Bosnia under the Influence of Turkish Rule, Andrić published his first collection of stories under the simple title Pripovetke (Tales) in the Belgrade Serbian Literary Association.

In his dissertation, Andrić himself points out that “in its content and in its basic idea, this discussion is related to other works” that he prepared “in another form and on other occasions.”

We cannot help but wonder what that connection is.

What works does Andrić’s statement refer to?

How much did the research of the history of Bosnia in connection with the dissertation help Andrić to see the nature of life in the Bosnian backwater during the Turkish occupation?

Apparently, the research undertaken by the young doctoral student, and the insights he gained, became an inexhaustible source and raw material for his short stories, and not only for those printed in 1924.

“These tales about the Turks and about ours are only a part of one work, which began with the tale ‘The Way of Alija Đerzelez’,” Andrić wrote in the introductory note for Tales.

From the moment he went to study in Zagreb and then Vienna and Krakow, Andrić traveled frequently.

Working as a diplomatic official in the Yugoslav embassies in some European cities, the writer got to know the people and regions of the countries in which he resided well.

Andrić published his first travelogue in 1914 under the title “Letter from Krakow” in the Croatian Movement, during his studies at the Jagiellonian University.

Above: Jagiellonian University logo

Living and studying in Graz, in 1923, Andrić translated his impressions of life and the country in the form of “notes from the road” into the text Through Austria.

Living in many capitals of interwar Europe inspired Andrić to write down his impressions.

However, he did not rely only on his own senses and observations, but carefully prepared for each trip and wrote in notebooks data from books on the history, culture and traditions of the country.

In his travelogues, Andrić primarily states what makes a country and its way of life specific.

Above: Europe, 1923

This is how I seek to write my travelogues.

In October 1926, he was assigned to the consulate in Marseille and again appointed vice-consul.

Above: Vieux Port, Marseille, France

On 9 December 1926, he was transferred to the Yugoslav embassy in Paris.

France suffered heavily during World War I in terms of lives lost, disabled veterans and ruined agricultural and industrial areas occupied by Germany as well as heavy borrowing from the United States, Britain, and the French people.

However, postwar reconstruction was rapid, and the long history of political warfare along religious lines was finally ended.

Parisian culture was world-famous in the 1920s, with expatriate artists, musicians and writers from across the globe contributing their cosmopolitanism, such as jazz music, and the French empire was in flourishing condition, especially in North Africa, and in Subsaharan Africa.

Above: Josephine Baker dances the Charleston at the Folies Bergère (1926)

Although the official goal was complete assimilation, few colonial subjects were actually assimilated.

Major concerns were forcing Germany to pay for the war damage by reparations payments and guaranteeing that Germany, with its much larger population, would never be a military threat in the future.

Efforts to set up military alliances worked poorly.

Relations remained very tense with Germany until 1924, when they stabilized thanks to large American bank loans.

Above: Germany (1919 – 1937)

France was part of the Allied force that occupied the Rhineland following the armistice.

Ferdinand Foch supported Poland in the Greater Poland Uprising and in the Polish–Soviet War and France also joined Spain during the Rif War.

Above: Ferdinand Foch

From 1925 until his death in 1932, Aristide Briand, as prime minister during five short intervals, directed French foreign policy by using his diplomatic skills and sense of timing to forge friendly relations with Weimar Germany as the basis of a genuine peace within the framework of the League of Nations.

He realised France could not contain the much larger Germany by itself or secure effective support from Britain or the League.

Above: Aristide Briand (1862 – 1932)

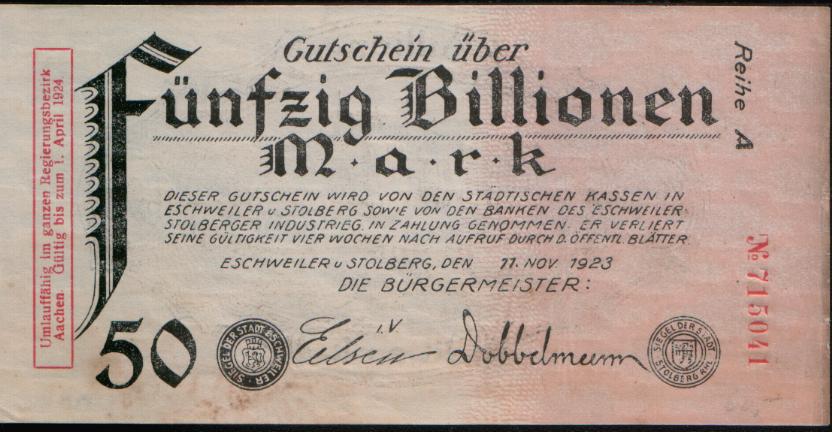

In January 1923, after Germany refused to ship enough coal as part of its reparations, France and Belgium occupied the industrial region of the Ruhr.

Germany responded with passive resistance, which included printing vast amounts of marks to pay for the occupation, which caused runaway inflation.

That heavily damaged the German middle class, whose savings became worthless, but also damaged the French franc.

The intervention was a failure, and in the summer of 1924, France accepted the American solution to the reparations issues, as expressed in the Dawes Plan.

It had American banks make long-term loans to Germany, which used the money to pay reparations.

The United States demanded repayment of the war loans although the terms were slightly softened in 1926.

All loans, payments and reparations were suspended in 1931, and everything was finally resolved in 1951.

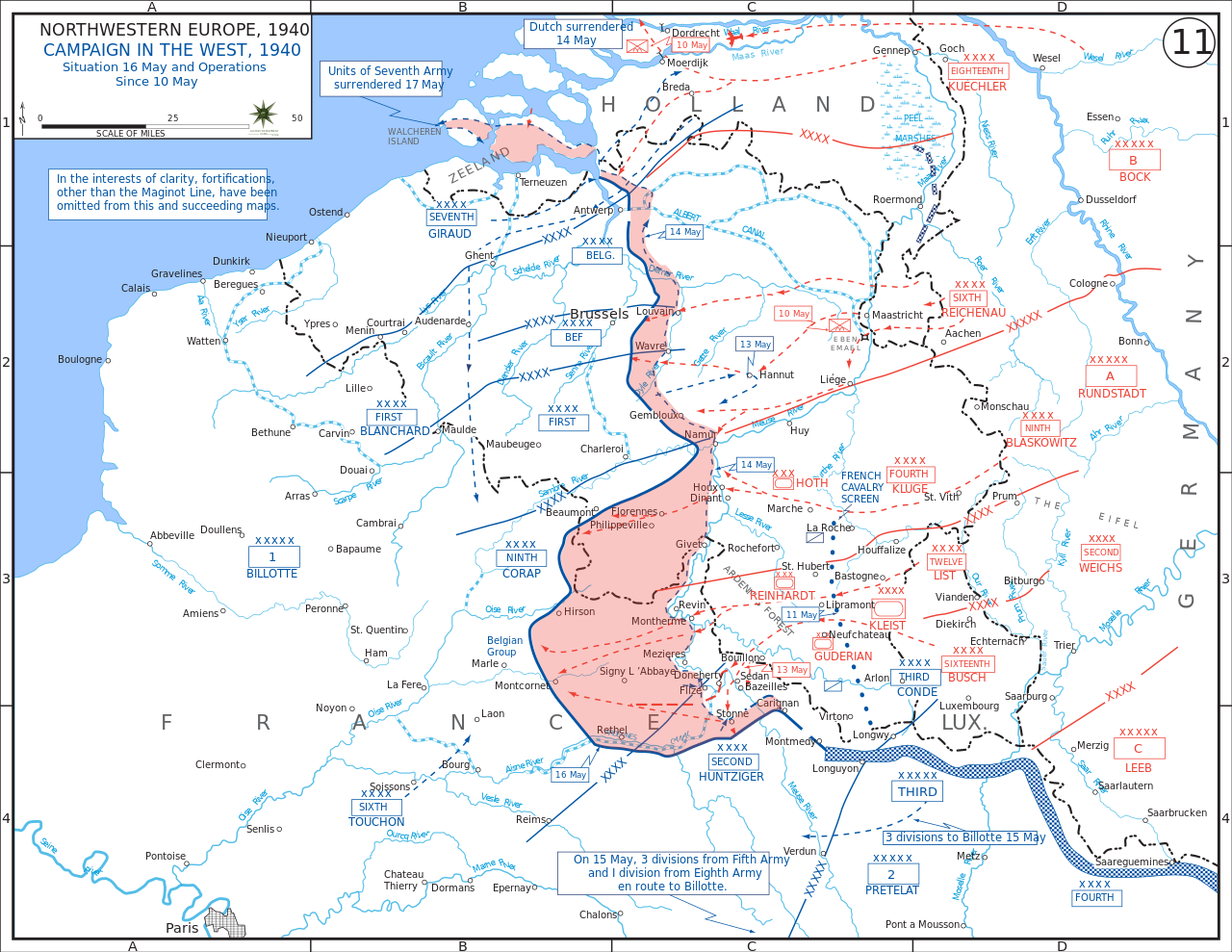

In the 1920s, France built the Maginot Line, an elaborate system of static border defences that was designed to stop any German invasion.

However, it did not extend into Belgium, and Germany attacked there in 1940 and went around the French defenses.

Military alliances were signed with weak powers in 1920–21, called the “Little Entente“.

Domestic politics in the 1920s were a product of unresolved problems left by the war and peace, especially the economics of reconstruction and how to make Germany pay for it all.

The great planners were Raymond Poincaré, Alexandre Millerand and Aristide Briand.

France had paid for the war with very heavy borrowing at home and from Britain and the United States.

Heavy inflation resulted, and in 1922, Poincaré became Prime Minister.

He justified his strong anti-German policies:

- Germany’s population was increasing, her industries were intact, she had no factories to reconstruct, she had no flooded mines.

- Her resources were intact, above and below ground.

- In fifteen or twenty years Germany would be mistress of Europe.

- In front of her would be France with a population scarcely increased.

Poincaré used German reparations to maintain the franc at a tenth of its prewar value and to pay for the reconstruction of the devastated areas.

Above: Raymond Poincaré (1860 – 1934)

Since Germany refused to pay nearly as much as Paris demanded, Poincaré reluctantly sent the French army to occupy the Ruhr industrial area (1922) to force a showdown.

The British strongly objected, arguing that it “would only impair German recovery, topple the German government, and lead to internal anarchy and Bolshevism, without achieving the financial goals of the French.“

The Germans practiced passive resistance by flooding the economy with paper money that damaged both the German and French economies.

The standoff was solved by American dollars in the Dawes Plan.

New York banks lent money to Germany for reparations to France, which then used the same dollars to repay the Americans.

Above: Wall Street, New York City

Throughout the early postwar period, Poincaré’s political base was the conservative nationalist parliament elected in 1920.

However, at the next election (1924), a coalition of Radical Socialists and Socialists called the “Cartel des gauches” (“Cartel of the Left“) won a majority, and Herriot of the Radical Socialist Party became prime minister.

He was disillusioned by the imperialist thrust of the Versailles Treaty, and sought a stable international peace in rapprochement with the Soviet Union to block the rising German revanchist movement.

Above: Édouard Herriot (1872 – 1957)

Andrić’s time in France was marked by increasing loneliness and isolation.

His uncle had died in 1924, his mother the following year, and upon arriving in France, he was informed that his aunt had died as well.

“Apart from official contacts,” he wrote Alaupović, “I have no company whatever.“

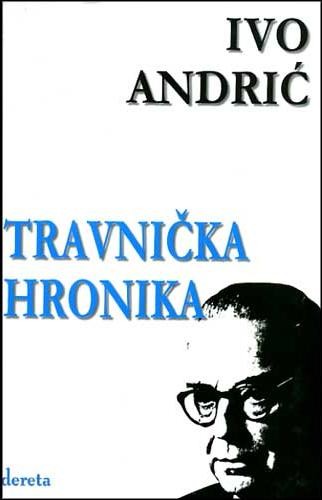

Andrić spent much of his time in the Paris archives poring over the reports of the French consulate in Travnik between 1809 and 1814, material he would use in Travnička hronika (The Travnik Chronicle), one of his future novels.

(The Travnik Chronicle (1945) is a historical novel written during the Second World War, based on the model of a European realistic novel.

It covers the period from 1807 until 1814 and therefore represents a classic novel more than any other Andrić’s novel.

The novel is narrated in the 3rd person and consists of a prologue, epilogue and 28 chapters.

Chronicle of Travnik is a seven-year fiction chronicle that deals with the stay of foreign consuls in that vizier’s city.

It begins with the arrival of the French consul, and ends with the departure of the second-appointed Austrian consul.

The novel is turned to history.

In the process of creating the Travnik Chronicle, Andrić used rich documentary material from the field of the history of civilization, ethnology and authentic writings about historical figures that are presented in the novel.)

Above: Travnik Fort

In April 1928, Andrić was posted to Madrid as vice-consul.

Above: Gran Via, Madrid, Spain

Spain’s neutrality in World War I spared the country from carnage, yet the conflict caused massive economic disruption, with the country experiencing at the same time an economic boom (the increasing foreign demand of products and the drop of imports brought hefty profits) and widespread social distress (with mounting inflation, shortage of basic goods and extreme income inequality).

Above: Flag of Spain

A major revolutionary strike was called for August 1917, supported by the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party, the UGT and the CNT, seeking to overthrow the government by means of a general strike.

The Dato government deployed the army against the workers to brutally quell any threat to social order, sealing in turn the demise of the cabinet and undermining the constitutional order.

The strike was one of the three simultaneous developments of a wider three-headed crisis in 1917 that cracked the Restoration regime, that also included a military crisis induced by the cleavage in the Armed Forces between Mainland and Africa-based ranks vis-à-vis the military promotion (and ensuing formation of juntas of officers that refused to dissolve upon request from the government), and a political crisis brought by the challenge posed by Catalan nationalism, whose bourgeois was emboldened by the economic upswing caused by the profits from exports to Entente powers during World War I.

During the Rif War, the crushing defeat of the Spanish Army in the so-called “Disaster of Annual” in the summer of 1921 brought in a matter of days the catastrophic loss of the lives of about 9,000 Spanish soldiers and the loss of all occupied territory in Morocco that had been gained since 1912.

This entailed the greatest defeat suffered by an European power in an African colonial war in the 20th century.

Above: Images of the Rif War

Spanish King Alfonso XIII tacitly endorsed the September 1923 coup by General Miguel Primo de Rivera that installed a dictatorship led by the latter.

Above: Spanish Alfonso XIII (1886 – 1941)

The regime enforced the State of War all over the country from September 1923 to May 1925 and, in permanent violation of the 1876 Constitution, wrecked with the legal-rational component of the constitutional compromise.

Attempts to institutionalise the regime (initially a Military Directory) were taken, in the form of a single official party (the Patriotic Union) and a consultative chamber (the National Assembly).

Preceded by a partial retreat from vulnerable posts in the interior of the protectorate in Morocco, Spain (in joint action with France) turned the tides in Morocco in 1925, and the Abd el-Krim-led Republic of the Rif started to see the beginning of its end after the Alhucemas landing and ensuing seizure of Ajdir, the heart of the Riffian rebellion.

The war had dragged on since 1917 and cost Spain $800 million.

The late 1920s were prosperous until the worldwide Great Depression hit in 1929.

Above: Miguel Primo de Riviera (1870 – 1930)

While in Madrid, Andric wrote (though did not then publish) essays on Simón Bolívar and Francisco Goya.

Above: Simón Bolívar (1783 – 1830)

Above: Francisco Goya (1746 – 1828)

That year he published the stories “Olujaci”, “Ispovijed” (Confession) and Most na Žepi (Bridge on the Žepa).

Bridge on the Zepa describes the construction of the bridge on Žepa, a river that often swells, and which the inhabitants have not yet managed to tame with the bridge.

So far, the river has taken away several wooden bridges (a similar theme, 20 years later, is dealt with in the Nobel Prize-winning novel On the Drina Bridge, so the story on the Bridge on the Žepa is considered an overture to the novel.

The narrator tells us the whole story in clear sentences.

The different segments of the story are firmly connected, although the vizier, as a narrator, often returns to the past and recalls his childhood in retrospect.

In Most na Žepi, Ivo Andrić describes many values, but also universal truths.

He emphasizes the efforts of man to adapt the world to himself and to fight against the forces of nature that sometimes destroy everything in front of him.

In a story such as The Bridge on Zepa, the symbolism of the bridge is reflected in the emphasized human urge to subdue the world and nature around it, but also to bring order to oneself – which the Grand Vizier Yusuf failed to do.

In the story, we can also see how art outlives the man who creates it, so it seems to overcome death itself.

On the other side of the story, we have a builder who does not seek friendship, praise or help from anyone.

He does not even crave material things, but lives for his work.

He did not ask for much, but with his work he provided a lot and made life easier for many people.

The story describes a number of difficulties encountered by the builder in the construction of the bridge, but in the end the successful outcome is successful.

The bridge was built, but the two characters end tragically.

Neymar dies of the plague, and the vizier suffers from the traumas experienced during his captivity, which lead him on a path of self-destruction.

In a figurative sense, the narrative is about man’s search for meaning.

Even after the goal was achieved (the construction of the bridge was completed), the characters did not achieve a sense of life satisfaction.

The story is written in the 3rd person.

Andric began work on the novel Prokleta avlija (The Cursed Court).

In Andrić’s novel, The Cursed Court is the name of the famous Constantinople dungeon, which Fr. Petar from Bosnia came to for unjustified reasons, when they sent him to Istanbul to do some monastic work.

It happened that the Turkish authorities caught a letter addressed to the Austrian internment in Constantinople, in which the persecution of the faithful by the Turkish authorities was described and the suspicion fell on Fr. Peter.

He was arrested and imprisoned in the pre-trial prison – “the Cursed Court“, where he remained for two months until he was sent on.

In The Cursed Court, Fra-Petar meets several people, who in this novel turn into a gallery of interesting characters.

There is the warden of the “Cursed Court” of Latifaga called Karadjoz , a prisoner of Chaim, a Jew from Smyrna, and then the central character from this novel is the prisoner Ćamil-effendi, a rich young Turk from Smyrna.

Fra-Petar learns from Haim, a young man’s fellow citizen, that he was imprisoned on suspicion that his study of consciousness was aimed at a rebellious plot against the sultan’s court, which was completely untrue.

Young Camil, the son of a rich Turk and a Greek woman, devoted himself to science and the solitary and ascetic way of life from an early age, which was especially emphasized by an unhappy and unhealthy love.

Namely, Camil fell in love with the daughter of a young Greek merchant, but for nationalistic and religious reasons, he did not want to give her to a Turk for a wife, but forcibly married her to a Greek outside Smyrna.

After that event, Ćamil completely closed himself in and became a kind of individual.

He surrounds himself with books and throws himself into science, showing a special interest in the consciousness of the Turkish Empire, of which he is particularly interested in one particular period – the time of Bayezid II and Jam-Sultan, his brother, whom Bayezid defeated twice in battle for the throne.

Then Jam sought refuge on the island of Rhodes, where Christian knights ruled.

From then on, the odyssey of Cem begins, who as a prisoner passes from the hands of various European rulers, and even the Pope himself, and they all use him as a trump card against the Turkish Empire, that is they threaten Bayazit that he will release him if he does not satisfy their various demands.

Ćamil is suspected of studying precisely that historical period, because it has similarities with the current situation at the court, where the sultan also has a rival brother, whom he declared insane and holds him captive. Jamil was sent to the Cursed Court, where he met Fr. Peter and told him about the life of Jam-Sultan, claiming that his life was identical with Jamil’s and that their destinies were the same.

After a while, they took him to a special prison, and one night during the interrogation, a fight broke out between him and the police.

It is not known whether the camels are taken out – alive or dead.

Fra-Peter never saw him again.

In June 1929, Andric was named secretary of the Yugoslav legation to Belgium and Luxembourg in Brussels.

Above: Images of Brussels, Belgium

Belgian King Albert returned from exile as a war hero, leading the victorious army and acclaimed by the population.

Above: King Albert I of Belgium (1875 – 1934)

In contrast, the government and other exiles came back discreetly.

Belgium had been devastated—not so much by combat, but rather by German seizure of valuable machinery.

Only 81 operable locomotives remained, out of the 3,470 available in 1914.

46 of 51 steel mills were damaged, with 26 destroyed totally.

More than 100,000 houses had been destroyed, as well as more than 120,000 hectares (300,000 acres) of farmland.

Above: Flag of Belgium

Waves of popular violence accompanied liberation in November and December 1918 and the government responded through the judicial punishment of collaboration with the enemy conducted between 1919 and 1921.

Shop windows were broken and houses sacked, men were harassed, and women’s heads were shaved.

Manufacturers who had closed their businesses sought the severe repression of those who had pursued their activities.

Journalists who had boycotted and stopped writing called for harsh treatment of the newspapers that submitted to German censorship.

Many people stigmatized profiteers and demanded justice.

Thus in 1918, Belgium was already confronted with the problems associated with occupation that most European countries only discovered at the end of World War II.

However, despite the status quo, Belgium recovered surprisingly quickly.

The first postwar Olympic Games were held in Antwerp in 1920.

In 1921, Luxembourg formed a customs union with Belgium.

German reparations to Belgium for damage incurred during the First World War was set at £12.5 billion pounds sterling.

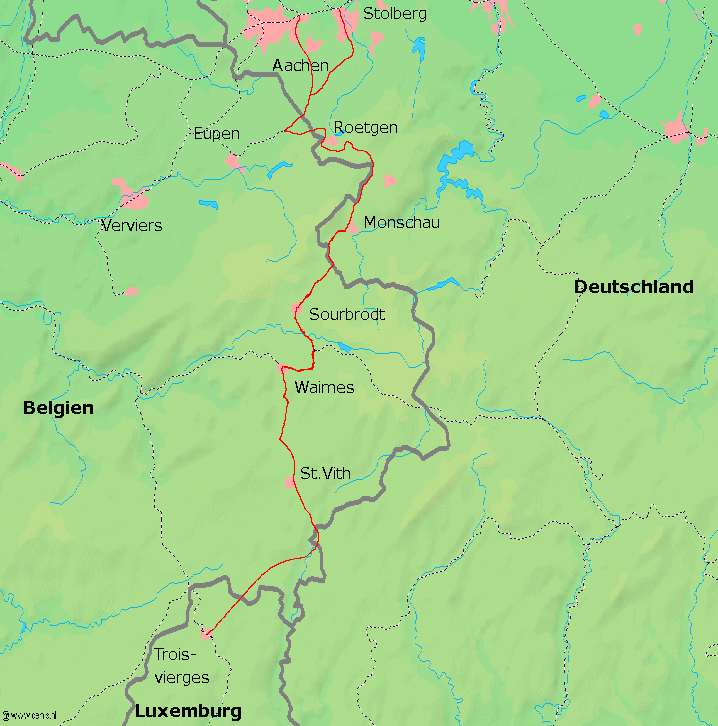

In 1919 under the Treaty of Versailles the area of Eupen-Malmedy, along with Moresnet was transferred to Belgium.

“Neutral Moresnet” was transferred to Belgium, as well as the Vennbahn railway.

Above: Map of the route of the Vennbahn

An opportunity was given to the population to “oppose” against the transfer by signing a petition, which gathered few signatures, in large part thanks to intimidation by local authorities, and all regions remain part of Belgium today.

Belgian requests to annex territory considered as historically theirs, from the Dutch, who were perceived as collaborators, was denied.

Between 1923 and 1926, Belgian and French soldiers were sent to the Ruhr in Germany to force the German government to agree to continue reparation payments.

The Occupation of the Ruhr led the Dawes Plan which allowed the German government more leniency in paying reparations.

The League of Nations in 1925 made Belgium the trustee for the former German East Africa which bordered the Belgian Congo to the east.

It became Rwanda-Urundi (or “Ruanda-Urundi“) (modern day Rwanda and Burundi).

Above: Coat of arms of Ruanda-Urundi

Although promising the League it would promote education, Belgium left the task to subsidised Catholic missions and unsubsidised Protestant missions.

As late as 1962, when independence arrived, fewer than 100 natives had gone beyond secondary school.

Above: The Cathedral of Our Lady of Wisdom at Butare (formally Astrida) in Ruanda

The policy was one of low-cost paternalism, as explained by Belgium’s special representative to the Trusteeship Council:

“The real work is to change the African in his essence, to transform his soul, and to do that one must love him and enjoy having daily contact with him.

He must be cured of his thoughtlessness, he must accustom himself to living in society, he must overcome his inertia.”

On 1 January 1930, Andric was sent to Switzerland as part of Yugoslavia’s permanent delegation to the League of Nations in Geneva, and was named deputy delegate the following year.

Above: Geneva, Switzerland

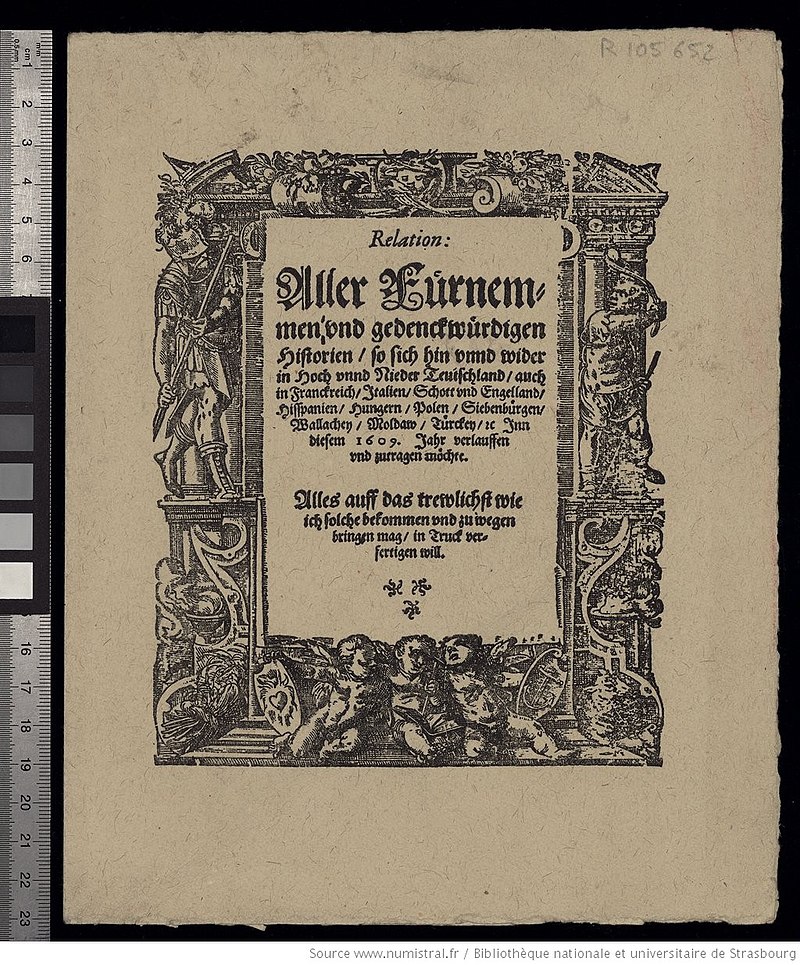

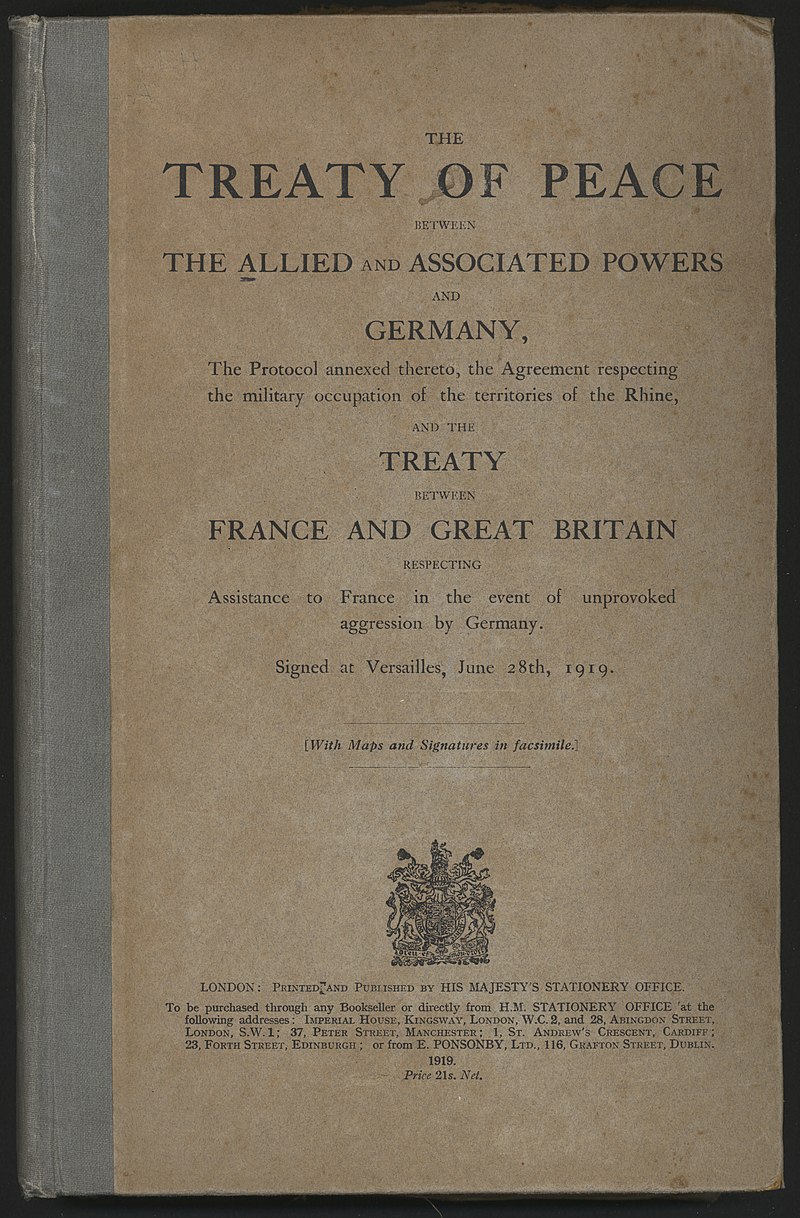

The League of Nations, abbreviated as LON (French: Société des Nations, abbreviated as SDN or SdN), was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace.

It was founded on 10 January 1920 following the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War.

In 1919 US President Woodrow Wilson won the Nobel Peace Prize for his role as the leading architect of the League.

The organisation’s primary goals, as stated in its Covenant, included preventing wars through collective security and disarmament, and settling international disputes through negotiation and arbitration.

Other issues in this and related treaties included labour conditions, just treatment of native inhabitants, human and drug trafficking, the arms trade, global health, prisoners of war, and protection of minorities in Europe.

The Covenant of the League of Nations was signed on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the Treaty of Versailles, and it became effective together with the rest of the Treaty on 10 January 1920.

The first meeting of the Council of the League took place on 16 January 1920, and the first meeting of Assembly of the League took place on 15 November 1920.

The diplomatic philosophy behind the League represented a fundamental shift from the preceding hundred years.

The League lacked its own armed force and depended on the victorious First World War Allies (France, the United Kingdom, Italy and Japan were the permanent members of the Executive Council) to enforce its resolutions, keep to its economic sanctions, or provide an army when needed.

The Great Powers were often reluctant to do so.

Sanctions could hurt League members, so they were reluctant to comply with them.

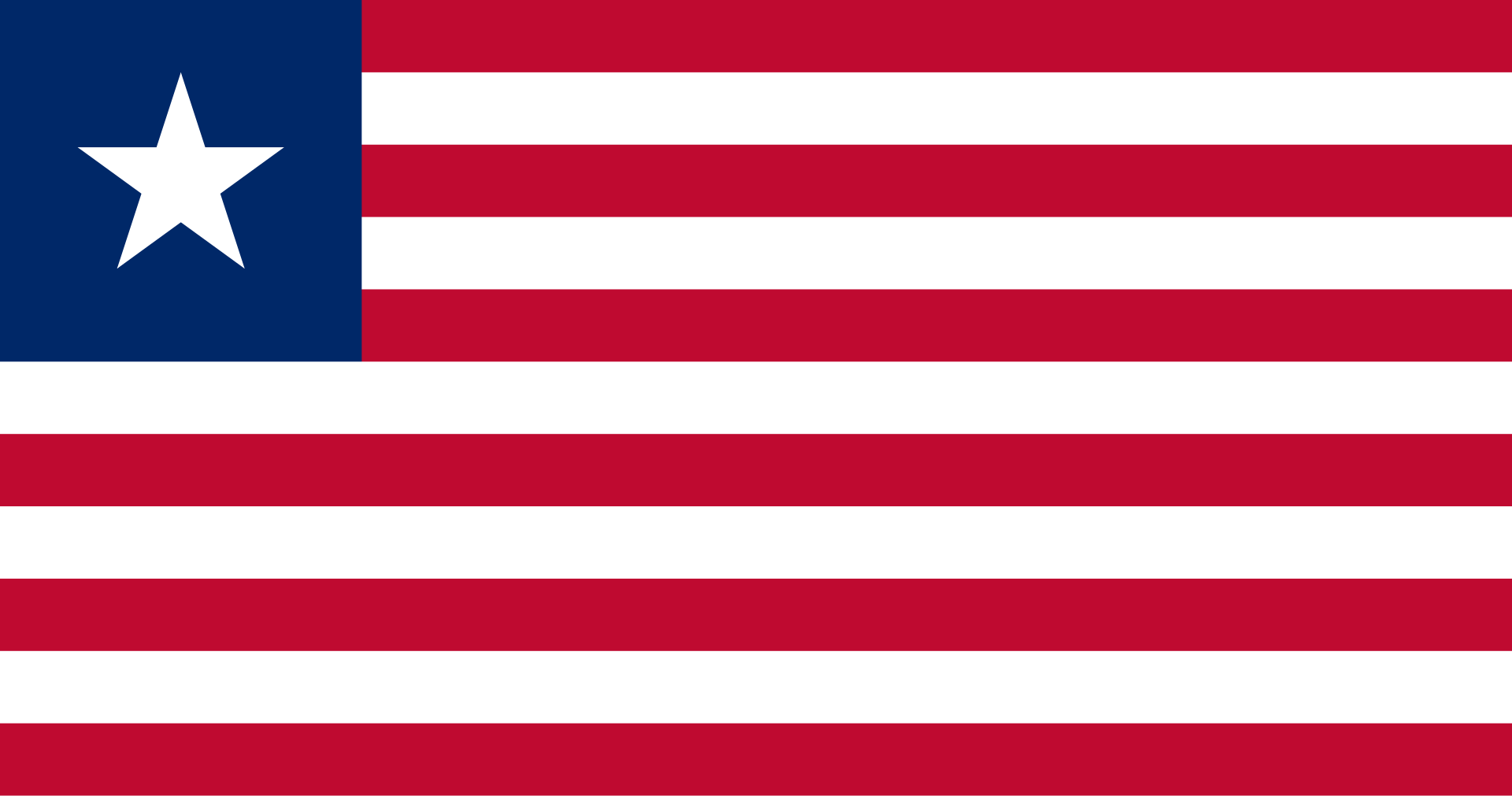

Following accusations of forced labour on the large American-owned Firestone rubber plantation and American accusations of slave trading, the Liberian government asked the League to launch an investigation.

The resulting commission was jointly appointed by the League, the United States, and Liberia.

In 1930, a League report confirmed the presence of slavery and forced labour.

The report implicated many government officials in the selling of contract labour and recommended that they be replaced by Europeans or Americans, which generated anger within Liberia and led to the resignation of President Charles D. B. King and his vice-president.

The Liberian government outlawed forced labour and slavery and asked for American help in social reforms.

Above: Flag of Liberia

The Mukden Incident, also known as the “Manchurian Incident“, was a decisive setback that weakened the League because its major members refused to tackle Japanese aggression.

Japan itself withdrew.

Under the agreed terms of the Twenty-One Demands with China, the Japanese government had the right to station its troops in the area around the South Manchurian Railway, a major trade route between the two countries, in the Chinese region of Manchuria.

In September 1931, a section of the railway was lightly damaged by the Japanese Kwantung Army as a pretext for an invasion of Manchuria.

The Japanese army claimed that Chinese soldiers had sabotaged the railway and in apparent retaliation (acting contrary to orders from Tokyo) occupied all of Manchuria.

They renamed the area Manchukuo, and on 9 March 1932 Japan set up a puppet government, with Pu Yi, the former emperor of China, as its executive head.

This new entity was recognised only by the governments of Italy, Spain and Nazi Germany.

The rest of the world still considered Manchuria legally part of China.

The League of Nations sent observers.

The Lytton Report appeared a year later (October 1932).

It declared Japan to be the aggressor and demanded Manchuria be returned to China.

Above: Chinese delegate addresses the League of Nations after the Mukden Incident in 1932

The report passed 42–1 in the Assembly in 1933 (only Japan voting against), but instead of removing its troops from China, Japan withdrew from the League.

In the end, as British historian Charles Mowat argued, collective security was dead:

- The League and the ideas of collective security and the rule of law were defeated; partly because of indifference and of sympathy with the aggressor, but partly because the League powers were unprepared, preoccupied with other matters, and too slow to perceive the scale of Japanese ambitions.

Above: The Mukden Incident Museum (literally, “September 18th History Museum“) in Shenyang, China

The League failed to prevent the 1932 war between Bolivia and Paraguay over the arid Gran Chaco region.

Although the region was sparsely populated, it contained the Paraguay River, which would have given either landlocked country access to the Atlantic Ocean, and there was also speculation, later proved incorrect, that the Chaco would be a rich source of petroleum.

Border skirmishes throughout the late 1920s culminated in an all-out war in 1932 when the Bolivian army attacked the Paraguayans at Fort Carlos Antonio López at Lake Pitiantuta.

Paraguay appealed to the League of Nations, but the League did not take action when the Pan-American Conference offered to mediate instead.

The war was a disaster for both sides, causing 57,000 casualties for Bolivia, whose population was around three million, and 36,000 dead for Paraguay, whose population was approximately one million.

It also brought both countries to the brink of economic disaster.

By the time a ceasefire was negotiated on 12 June 1935, Paraguay had seized control of most of the region, as was later recognised by the 1938 truce.

Above: Paraguayan soldiers at Alihuatá, 1932

In 1933, Andrić returned to Belgrade.

Two years later, he was named head of the political department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

On 5 November 1937, Andrić became assistant to Milan Stojadinović, Yugoslavia’s Prime Minister and Foreign Minister.

Above: National Assembly, Belgrade

Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast Europe and Central Europe for most of the 20th century.

It came into existence after World War I in 1918 under the name of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes by the merger of the provisional State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (it was formed from territories of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire) with the Kingdom of Serbia, and constituted the first union of the South Slavic people as a sovereign state, following centuries in which the region had been part of the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary.

Peter I of Serbia was its first sovereign.

The kingdom gained international recognition on 13 July 1922 at the Conference of Ambassadors in Paris.

The official name of the state was changed to Kingdom of Yugoslavia on 3 October 1929.

On 20 June 1928, Serb deputy Puniša Račić shot at five members of the opposition Croatian Peasant Party in the National Assembly, resulting in the death of two deputies on the spot and that of leader Stjepan Radić a few weeks later.

Above: Punisa Racic (1886 – 1944)

On 6 January 1929, King Alexander I got rid of the constitution, banned national political parties and assumed executive power and renamed the country Yugoslavia.

He hoped to curb separatist tendencies and mitigate nationalist passions.

He imposed a new constitution and relinquished his dictatorship in 1931.

However, Alexander’s policies later encountered opposition from other European powers stemming from developments in Italy and Germany, where Fascists and Nazis rose to power, and the Soviet Union, where Joseph Stalin became absolute ruler.

None of these three regimes favored the policy pursued by Alexander I.

In fact, Italy and Germany wanted to revise the international treaties signed after World War I, and the Soviets were determined to regain their positions in Europe and pursue a more active international policy.

Alexander attempted to create a centralised Yugoslavia.

He decided to abolish Yugoslavia’s historic regions, and new internal boundaries were drawn for provinces or banovinas.

The banovinas were named after rivers.

Many politicians were jailed or kept under police surveillance.

The effect of Alexander’s dictatorship was to further alienate the non-Serbs from the idea of unity.

During his reign the flags of Yugoslav nations were banned.

Communist ideas were banned also.

Above: King Alexander I (1888 – 1934)

The king was assassinated in Marseille during an official visit to France in 1934 by Vlado Chernozemski, an experienced marksman from Ivan Mihailov’s Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization with the cooperation of the Ustaše, a Croatian fascist revolutionary organisation.

Alexander was succeeded by his eleven-year-old son Peter II and a regency council headed by his cousin, Prince Paul.

Above: The funeral of King Alexander at Belgrade

The international political scene in the late 1930s was marked by growing intolerance between the principal figures, by the aggressive attitude of the totalitarian regimes and by the certainty that the order set up after World War I was losing its strongholds and its sponsors were losing their strength.