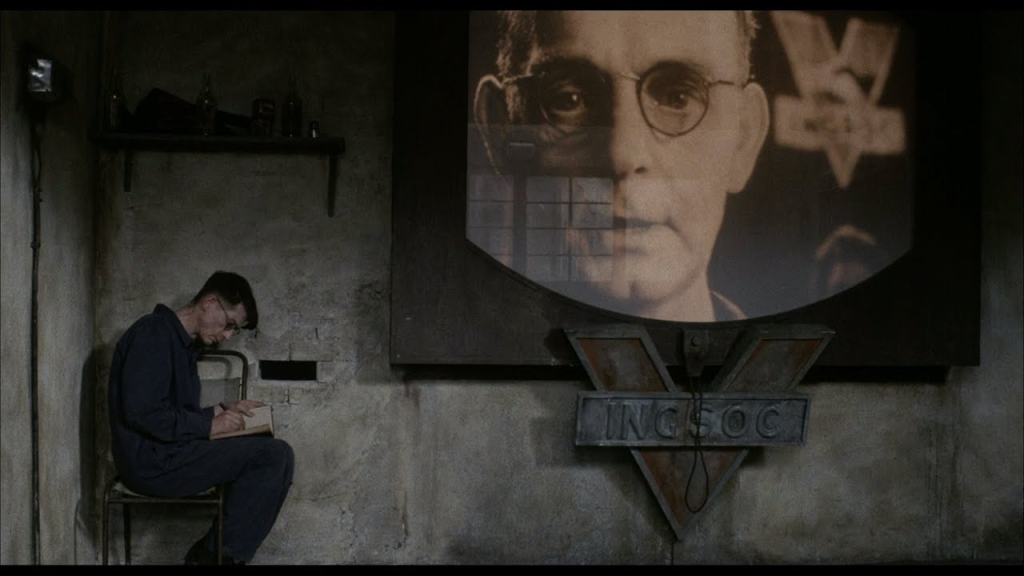

Barlinnie Prison, Glasgow, Scotland

17 April 1976

“I thought of the beautiful cool evening, how I long to be walking in it outside this cell.

All of this took place while I sat in the semi-dark reading a book.

The thoughts on freedom were only momentary but so powerful that they seem to tear my soul apart.

There is something about being alone in a cell, about the inability to rise from a chair, open a door and speak to someone.

I would like to get up this minute and discuss this subject with someone.

I would like to put these feelings into a piece of sculpture and although sitting typing out the feelings is important there is a tremendous amount of strain and frustration attached to it.

During these periods I find it hard to read a book or watch TV, which I hardly do anyway.

The only solution is to tackle the mood and try to do something about it.“

(Jimmy Boyle)

Above: Jimmy Boyle, Barlinnie Prison, Glasgow, Scotland

Eskişehir, Türkiye

Wednesday 17 April 2024

Above: Sazova Park, Eskişehir, Türkiye

Jimmy Boyle is a Scottish former gangster and convicted murderer who became a sculptor and novelist after his release from prison.

In 1967, Boyle (23) was sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder of another gangland figure, William “Babs” Rooney.

He served 14 years before his release in 1980.

Boyle has always denied killing Rooney, but has acknowledged having been a violent and sometimes ruthless moneylender from the Gorbals, one of the roughest and most deprived areas of Glasgow.

During his incarceration in the special unit of Barlinnie Prison, he turned to art, with the help of the special unit’s art therapist, Joyce Laing.

Above: Jimmy Boyle

He wrote an autobiography, A Sense of Freedom (1977), which was later turned into a film of the same name.

In 1980, while still in prison, Boyle married psychiatrist Sara Trevelyan.

In 2017, Trevelyan wrote Freedom Found, a book about her 20-year marriage to Boyle.

In an interview after her book’s publication, she stated that she had never felt unsafe with him.

Upon his release from prison on 26 October 1981, he moved to Edinburgh to continue his artistic career.

He designed the largest concrete sculpture in Europe called “Gulliver” for the Craigmillar Festival Society in 1976.

Above: “Gulliver“, Edinburgh, Scotland

In 1983, Boyle set up the Gateway Exchange with Trevelyan and artist Evlynn Smith:

A charitable organisation offering art therapy workshops to recovering drug addicts and ex-convicts.

Though the project secured funding from private sources (including actor Sean Connery, comedian Billy Connolly and John Paul Getty), it lasted only a few years.

In 1994, his son James, a drug addict, was murdered in the Oatlands neighbourhood of Glasgow.

Boyle has published Pain of Confinement: Prison Diaries (1984) and a novel, Hero of the Underworld (1999).

The latter was adapted for a French film, La Rage et le Rêve des Condamnés (The Anger and Dreams of the Condemned), which won the best documentary prize at the Fifa Montréal awards in 2002.

He also wrote a novel, A Stolen Smile, which is about the theft of the Mona Lisa and how it ends up hidden on a Scottish housing scheme.

Clearly our Jimmy has led an interesting life, but is his life an interesting story?

Above: Jimmy Boyle

From the cursory bio that Wikipedia provides it seems that Jimmy never studied literature at some fancy university.

That being said, he is a published diarist and novelist.

He somehow had to learn how to write.

A person can learn how to write, because I am still learning.

Jimmy wasn’t doomed to be just an ex con.

He learned craft, things that worked for him, that he could understand and use right away.

Craft can be taught and with diligence and practice, I, you, everybody, can improve our writing.

To break through with this thing called craft, you will need to be your own disciplinarian.

James Scott Bell recommends what it takes to learn:

- Get motivated.

Write a statement of purpose, one that gets you excited.

“Today I resolve to take writing seriously, to keep going and never stop, to learn everything I can and make it as a writer.“

Put it on your wall where you can see it every day.

Come up with your own item of visual motivation.

(During my first Christmas here in Eskişehir our staff “Christmas” party had a Secret Santa arrangement where we would receive a gift from someone anonymously and give one in return to someone else anonymously.

Through the wonders of Photoshop, a colleague created a montage of me standing with Charles Dickens in front of the Canadian Parliament Buildings in Ottawa beneath the caption “A Tale of Two Legends“.

That my colleague felt that I could be (one day) comparable to Dickens remains a great motivation for me.)

Above: Charles Dickens (1812 – 1870)

Go to bookstores and browse.

Look at the author’s pictures and bios.

Read their openings.

And think:

“I can do this!“

Find some ritual that gets your creative juices flowing.

Don’t waste it.

Turn it into words on a page.

2. Try stuff.

Try out what you learn, see if you get it and try some more.

Take the time to digest what you learn and then apply what you learn to your own writing.

3. Stay loose.

Write freely and rollickingly.

4. First get it written, then get it right.

“Let the world burn through you.

Throw the prism light, white hot, on paper.”

(Zen in the Art of Writing, Ray Bradbury)

5. Set a quota.

Writing is how you learn to write.

Writing daily, as a discipline, is the best way to learn.

Most successful writers make a word goal and stick to it.

The daily writing of words, once it becomes a habit, will be the most fruitful discipline of your writing life.

You will be amazed at how productive you will become and how much you will learn about the craft.

“I only write when I am inspired.

I make sure I am inspired every morning at 9 a.m.“

(Peter DeVries)

Above: American writer Peter De Vries (1910 – 1993)

6. Don’t give up.

The main difference between successful writers and unsuccessful writers is persistence.

There are legions of published novelists who went years and years without acceptance.

They continued to write because that is what they were inside:

Writers.

KEEP WRITING.

“When first we mean to build, we first survey the plot, then draw the model.”

(Henry IV, Part 2, William Shakespeare)

Above: William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616)

Plot happens.

But does it work?

Does it connect with readers?

What is this story about?

Is anything happening?

Why should you keep reaading?

Why should you care?

The what happens is your plot.

When you get right down to it, there is something uniquely satisfying in being gripped by a great plot, in begrudgiıng whatever real world obligations might prevent you from finding out what happens next.

It is especially satisfying to surrender to an author who is utterly in command of a thrilling and original story, an author capable of playing us like fish, of letting us get worried, then riled up, then complacent and then finally blowing us away when the final shocks are delivered.

While glorious prose is a fine thing, without an enthralling story, it is just so much verbal tapioca.

What the reader seeks is an experience that is other.

Other than what he normally sees each day.

Story is how he gets there.

A good story transports the reader to a new place via experience.

Not through arguments or facts, but through the illusion that life is taking place on the page.

Not the reader’s life.

Someone else’s.

Your characters’ lives.

An author creates a dream.

When we dream, we experience that as reality.

In reality there is one reason, and one reason only, that readers get excited about a novel:

Great storytelling.

Can creative writing be taught?

No.

Can the love of language be taught?

No.

Can a gift for stroytelling be taught?

No.

But….

Like most writers, you learn to write by writing and by reading books.

Writers learn by reading the work of their predecessors and counterparts.

They study meter with Ovid, plot construction with Homer, comedy with Aristophanes.

Above: Roman poet Ovid (43 BC – AD 18)

Above: Bust of Greek poet Homer (8th century BC)

Above: Bust of Greek playwright Aristophanes (446 – 386 BC)

They hone their prose by absorbing the sentences of Montaigne and Samuel Johnson.

Above: French philosopher Michel de Montaigne (1533 – 1592)

Above: English writer / lexicographer Samuel Johnson (1709 – 1784)

And who could ask for better teachers?

Though writers have learned from the masters in a formal, methodical way – Harry Crews has described taking apart a Graham Greene novel to see how many chapters it contained, how much time it covered, how Greene handled pacing and tone and point of view – the truth is that this sort of education more often involves a kind of osmosis.

Above: English writer Graham Greene (1904 – 1991)

For example, copying out long passages of a great writer’s work, you will notice that your own work should become, however briefly, just a little more fluent.

In the ongoing process of becoming a writer, I read and re-read the authors I have most loved.

I read for pleasure, but also more analytically, conscious of style, of diction, of how sentences were formed and information conveyed, how the writer structured their plot, created characters, employed detail and dialogue.

Writing, like reading, is done one word at a time, one punctuation mark at a time, putting every word on trial for its life.

Writers learn that which cannot be taught.

Writers learn to write by practice, hard work, repeated trial and error, success and failure.

And from the books they admire.

My blog is a sort of a “what-happened-on-this day” creation.

I like to focus on the birthdays of other writers or mention what holiday is being commemorated on this day.

Imagine we are about to be plunged into a story – any story in the world.

The curtain rises.

The cinema darkens.

We turn to the first paragraph of a novel.

The narrator utters the timeless formula:

“Once upon a time…“

John Ford (17 April 1586 – 1639) was an English playwright and poet born in Ilsington in Devon, England.

His plays deal mainly with the conflict between passion and conscience.

Although remembered primarily as a playwright, he also wrote a number of poems on themes of love and morality.

Above: English writer John Ford

Ford is best known for the tragedy ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore (1633), a family drama with a plot line of incest.

The play’s title has often been changed in new productions, sometimes being referred to as simply Giovanni and Annabella — the play’s leading, incestuous brother-and-sister characters.

In a 19th-century work it is coyly called The Brother and Sister.

Shocking as the play is, it is still widely regarded as a classic piece of English drama.

It has been adapted to film at least twice:

- My Sister, My Love (Sweden, 1966)

- ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore (Belgium, 1978).

On the face of it, so limitless is the human imagination and so boundless the realm of the storyteller’s command, we think that literally anything could happen next…

His plays deal with conflicts between individual passion and conscience and the laws and morals of society at large.

Ford had a strong interest in abnormal psychology that is expressed through his dramas.

While virtually nothing is known of Ford’s personal life, one reference suggests that his interest in melancholia may have been more than merely intellectual.

“Deep in a dump alone John Ford was gat,

With folded arms and melancholy hat.”

(Choice Drollery, Joseph Woodfall Ebsworth)

The story will have a hero or heroine or both, a central figure or figures on whose fate our interest in the story ultimately rests.

Someone with whom we can identify.

The Laws of Candy is set in Crete — “Candy” and “Candia” being archaic names for the island.

In Ford’s fictional Candy, two unusual laws are in the statute books.

One is a (highly impracticable) law against ingratitude:

A citizen who is accused of ingratitude by another, and fails to make amends, can be sentenced to death.

The second law holds that after a military victory, the soldiers will select the one of their number who has done the most to achieve the success.

“Tell us, pray, what devil this melancholy is, which can transform men into monsters.“

(The Lover’s Melancholy, John Ford)

The second law is the cause of the play’s conflict.

The forces of Candy have just won a great victory over the invading Venetians.

(Historically, Venice conquered Crete in the early 13th century [1209 – 1217] and ruled the island until 1669, though with many rebellions by the local populace.)

The commander of the army, Cassilanes, the leading soldier of his generation, expects to receive the acclaim of the troops, and is incensed to find that he has a rival in his own son, Antinous, who has distinguished himself in his first battle.

The father’s concern is real:

Antinous wins the approval of the soldiers.

Paradoxically, Cassilanes is even more outraged when Antinous claims his reward from the state — and names a bronze statue of his father.

To Cassilanes, this is only one more assertion of the son’s assumed power.

Above: Island of Crete, Greece

“Melancholy is not, as you conceive, indisposition of body, but the mind’s disease.“

(The Lover’s Melancholy, John Ford)

Cassilanes is certainly an irascible old man — but he has an additional grievance.

He has mortgaged his estates to pay the troops, who otherwise would not have fought.

The state is in no hurry to rectify the matter.

The owner of the mortgage is Gonzalo, an ambitious Venetian lord.

Gonzalo is the play’s Machiavellian villain.

He plots and manipulates with the goal of becoming both the King of Candy and the Duke of Venice.

Gonzalo, however, makes two mistakes.

One is that he takes a young Venetian prisoner of war, Fernando, into his confidence, relying on their shared nationality.

When Cassilanes retreats to a poverty-stricken retirement, Gonzalo arranges for Fernando to live in the general’s little household to further his machinations.

Fernando is a noble young man, in mind as well as in birth.

Once he falls in love with Cassilanes’ daughter Annophel, he reveals Gonzalo’s plots.

Above: Location of the island of Crete (Kriti) (in red)

“Green indiscretion, flattery of greatness,

Rawness of judgement, wilfulness in folly,

Thoughts vagrant as the wind, and as uncertain.“

(The Broken Heart, John Ford)

Gonzalo’s second mistake is to fall in love himself, with the Princess Erota.

The play’s list of dramatis personae describes her as “a Princess, imperious, and of an overweaning Beauty“.

Royal, rich, witty, and beautiful, she is also extravagantly vain.

She is loved by many men, including a Prince of Cyprus named Philander, but scorns them all.

Until, that is, she meets Antinous and falls in love with him.

Motivated by that love, she manipulates the vain Gonzalo into selling her Cassilanes’ mortgage and also into committing his plots and plans to writing.

Above: Map of Crete

“Love is the tyrant of the heart.

It darkens reason, confounds discretion, deaf to counsel.

It runs a headlong course to desperate madness.“

(The Lover’s Melancholy, John Ford)

In the play’s final climactic scene, the other odd law of Candy comes into play.

Cassilanes comes before the Senate with a complaint of ingratitude against his son.

Antinous, resigned to death, refuses to defend himself.

But Erota makes a similar complaint of ingratitude against Cassilanes — which provokes Antinous to make the same complaint against her, in a sort of round-robin festival of egomania.

The solution to this tangle comes when Annophel enters and makes her own complaint of ingratitude against the Senate of Candy, for its treatment of her father.

Above: Firkas fortress in Chania, Crete, Greece

“Glories of human greatness are but pleasing dreams and shadows soon decaying.“

(The Broken Heart, John Ford)

The befuddled Senate turns the matter over to the Cypriot prince Philander for judgment.

Philander prevails on Cassilanes to repent and withdraw his complaint against Antinous, which allows all the subsequent difficulties to be resolved.

Almost as an afterthought, the Cretans and Venetians unite in condemning Gonzalo to punishment.

Erota’s pride is humbled (we know this, since she tells us so herself), and she accepts her most constant (and noble) suitor, Prince Philander, as her spouse.

Above: Venetian harbour in Chania, Crete, Greece

“The joys of marriage are Heaven on Earth,

Life’s Paradise, great princess, the soul’s quiet,

Sinews of concord, earthly immortality,

Eternity of pleasures, no restoratives

Like to a constant woman!“

(The Broken Heart, John Ford)

In The Witch of Edmonton, Elizabeth Sawyer is a poor, lonely, and unfairly ostracized old woman, who turns to witchcraft after having been unjustly accused of it, having nothing left to lose.

A talking devil-dog Tom (performed by a human actor) appears, becoming her familiar and only friend.

With Tom’s help, Sawyer causes one of her neighbours to go mad and kill herself, but otherwise she does not achieve very much, since many of those around her are only too willing to sell their souls to the Devil all by themselves.

The play is divided fairly rigidly into separate plots, which only occasionally intersect or overlap.

Alongside the main story of Elizabeth Sawyer, the other major plotline is a domestic tragedy centering on the farmer’s son Frank Thorney.

Frank is secretly married to the poor but virtuous Winnifride, whom he loves and believes is pregnant with his child, but his father insists that he marry Susan, elder daughter of the wealthy farmer Old Carter.

Frank weakly gives in to a bigamous marriage but then tries to flee the county with Winnifride disguised as his page.

When the doting Susan follows him, he stabs her.

At this point, the witch’s dog Tom is present on stage.

It is left ambiguous whether Frank remains a fully responsible moral agent in the act.

Frank inflicts superficial wounds on himself, so that he can pretend to have been attacked.

He attempts to frame Warbeck, Susan’s former suitor, and Somerton, suitor of Susan’s younger sister Katherine.

While the kindly Katherine is nursing her supposedly incapacitated brother-in-law, however, she finds a bloodstained knife in his pocket and immediately guesses the truth, which she reveals to her father.

The devil-dog is on stage again at this point, and “shrugs for joy” according to the stage direction, which suggests that he has brought about Frank’s downfall.

“Tempt not the stars, young man.

Thou canst not play with the severity of fate.”

(The Broken Heart, John Ford)

Frank is executed for his crime at the same time as Mother Sawyer, but he, in marked contrast to her, is forgiven by all.

The pregnant Winnifride is taken into the family of Old Carter.

The play thus ends on a relatively happy note — Old Carter enjoins all those assembled at the execution:

“So, let’s every man home to Edmonton with heavy hearts, yet as merry as we can, though not as we would.“

“Revenge proves its own executioner.“

(The Broken Heart, John Ford)

The note of optimism is also heard in the play’s other main plot, centering on the Morris dancing yokel Cuddy Banks, whose invincible innocence allows him to emerge unscathed from his own encounters with the dog Tom.

He eventually banishes the dog from the stage with the words:

“Out and avaunt!“

“He hath shook hands with time.“

(The Broken Heart, John Ford)

Despite the optimism of the play’s ending it remains clear that the execution of Mother Sawyer has done little or nothing to purge the play’s world of an evil to which its inhabitants are only too ready to turn spontaneously.

Firstly, the devil-dog has not been destroyed.

Indeed it resolves to go to London and corrupt souls there.

Secondly, the village’s voice of authority, the lord of the manor Sir Arthur Clarington, is represented as untrustworthy.

Mother Sawyer utters a lengthy tirade indicting his lechery – He had previously had an affair with Winnifride, which she now repents – and general corruption:

A charge which the play as a whole supports.

We are introduced to our central figure(s) in an imaginary world.

The general scene is set.

“Once upon a time…“

We are taken out of our present place and time into an imaginary realm where the story is to unfold.

We are introduced to our central figure(s).

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

The Witch of Edmonton may be very ready to capitalize on the sensational story of a witch, but it does not permit an easy and comfortable demonization of her.

It presents her as a product of society rather than an anomaly in it.

Something happens.

Some event, some encounter, precipates the story’s action, giving it a focus.

“Once upon a time there was Someone living Somewhere.

Then one day Something happened.”

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

The plot of The Fair Maid of the Inn concerns the intertwined fortunes of two prominent Florentine families.

Alberto is the Admiral of Florence.

He is married to Mariana.

Their children are Cesario and Clarissa.

Baptista, another old sailor, is a friend of Alberto, and father of Mentivole.

Like their fathers, Cesario and Mentivole are friends.

Alberto’s is a stable nuclear family.

Mariana is a doting mother, especially in regard to Cesario.

Baptista’s situation is less happy:

Fourteen years earlier, he, a widower in his prime, contracted a secret marriage with Juliana, a niece of the Duke of Genoa.

After a short three months of contentment, the Genoese Duke discovered the marriage, exiled Baptista, and sequestered Juliana.

He has not seen her since.

We meet a little boy called Aladdin, who lives in a city in China.

One day a sorcerer arrives and leads him out of the city to a mysterious cave.

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

This situation is delineated in the play’s long opening scene.

At the scene’s opening, Cesario warns Clarissa to safeguard her virginity and her reputation, but Clarissa responds by reproving her brother about his rumoured affair with Biancha, the 13-year-old daughter of a local tavernkeeper.

(She’s the “fair maid” of the title.)

Cesario protests that his connection with the girl is above reproach:

Biancha, he says, is beautiful but chaste.

By the scene’s close, Mentivole expresses his love for Clarissa.

She responds positively and gives him a diamond ring as a token of her affection and commitment.

We meet the Scottish General Macbeth, who has just won a great victory over his country’s enemies.

Then, on his way home, he encounters mysterious witches.

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

Friends though they are, Cesario and Mentivole have a falling-out over a horse race.

They quarrel, lose their tempers and draw their swords to fight.

They are separated by other friends, but only after Cesario is wounded.

The affair escalates into a major feud between the two families.

Alberto is called away by his naval duties and is soon reported dead.

Mariana fears that her son will be killed in the feud.

To prevent this, she announces (falsely) to the Duke and his court that Cesario is not really Alberto’s son.

Early in their marriage, she maintains, Alberto had wanted an heir, but the couple did not conceive.

Mariana exploited her husband’s absences at sea to pass off a servant’s child as her own.

Thus he is no longer Alberto’s son and safe from Baptista’s enmity.

But the Duke sees the injustice done against Cesario and decrees that the now-widowed Mariana should marry the young man and endow him with three-quarters of Alberto’s estate.

The remaining share will serve as Clarissa’s dowry.

We meet a girl called Alice, wondering how to amuse herself in the summer heat.

Suddenly she sees a white rabbit running past and vanishing down a mysterious hole.

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

Cesario is amenable to this arrangement — but Mariana assures him that any marriage between them will never be consummated.

Cesario proposes a marriage between himself and Clarissa, though both women reject the idea out of hand.

And even Biancha turns against Cesario, when she comes to understand that he is not serious about marrying her.

Eventually matters are set right when Alberto returns to Florence.

Not dead, he was instead captured by the Turks, but rescued by Prospero, a captain in the service of Malta.

Prospero is an old friend of both Alberto and Baptista.

He is able to inform the world of the fate of Juliana, and the daughter that Alberto didn’t know Baptista had.

She is Biancha, the supposed daughter of the tavernkeeper.

This good news allows the compounding of all the previous difficulties.

The quarrel between Alberto and Baptista is resolved.

Cesario is restored to his rightful place as Alberto’s son.

Cesario and Biancha can marry, as can Mentivole and Clarissa.

Above: Firenze (Florence), Italia (Italy)

We see the great detective Sherlock Holmes sitting in his Baker Street lodgings.

Then there is a knock at the door.

A visitor enters to present him with his next case.

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

The play has a comic subplot centered on Biancha, her supposed parents the Host and Hostess of the tavern, and their quests.

The comedy features a mountebank (a charlatan) and his clownish assistant, and their victims.

An event, a summons, provides the call to action which will lead the hero out of their initial state into a series of adventures or experiences which will transform their lives.

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

The play’s storytelling is rough and rather inconsistent, most likely due to the multiple hands involved in its authorship.

The action the hero is drawn into will involve conflict and uncertainty, because without conflict and uncertainty there is no story.

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

In The Queen, Alphonso, the play’s protagonist, is a defeated rebel against Aragon.

He has been condemned to death and is about to be executed.

The Queen of Aragon (otherwise unnamed) intercedes at the last moment and learns that Alphonso’s rebellion is rooted in his pathological misogyny.

The prospect of being ruled by a woman was too much for him to bear.

The Queen is struck with love at first sight.

She is, in her way, just as irrational as Alphonso is in his.

The Queen pardons Alphonso and marries him.

Alphonso requests a seven-day separation, to enable him to set aside his feelings against women.

The Queen grants his request.

The week extends to a month and the new King still avoids his Queen.

The intercession of her counsellors, and even her own personal appeal, make no difference.

In a bitter confrontation, Alphonso tells the Queen:

“I hate thy sex.

Of all thy sex, thee worst.“

The story carries us towards some kind of resolution.

Every story which is complete, and not just a fragmentary string of episodes and impressions, must work up to a climax, where conflict and uncertainty are usually at their most extreme.

Every story leads its central character in one of two directions.

Either they end happily with a sense of liberation, fulfilment and completion.

Or they end unhappily in some form of discomfiture, frustration or death.

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

One man, however, sees a solution to the problem.

The psychologically sophisticated Muretto half-counsels, half-manipulates Alphonso into a more positive disposition toward the Queen.

Muretto praises the Queen’s beauty to Alphonso and simultaneously arouses his jealousy by suggesting that she is sexually active outside her marriage.

Muretto functions rather like a modern therapist to treat Alphonso’s psychological imbalance.

The psychological manipulation works, in the sense that Alphonso begins to value the Queen only after he thinks he has lost her to another man.

To say that stories either have happy or unhappy endings may seem such a commonplace that one almost hesitates to utter it, but it has to be said, because it is the most important single thing to be observed about stories.

Around that one fact, around what is necessary to bring a story to some sort of an ending, revolves the whole of their extraordinary significance in our lives.

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

Yet with two such passionate individuals, reconciliation cannot come easily.

Alphonso condemns the Queen to death.

She can be reprieved only if a champion comes forth to defend her honour by meeting the king in single combat.

The Queen, however, is determined to bow to her husband’s will no matter the price and demands that all her followers swear they will not step forward in her cause.

Aristotle first observed that a satisfactory story – a story which is a “whole” – must have “a beginning, a middle and an end“.

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

Above: Bust of Greek philosopher Aristotle (384 – 322 BC)

The play’s secondary plot deals with the love affair of the Queen’s General Velasco, the valiant soldier who defeated Alphonso, and the widow Salassa.

Velasco has the opposite problem from Alphonso:

He idealises his love for Salassa, terming her “the deity I adore“.

He allows her to dominate their relationship.

(Velasco’s friend and admirer Lodovico has a low opinion of Salassa, calling her a “frail commodity“, a “paraquetto“, a “wagtail“.)

Salassa indulges in her power over Velasco by asking him to give up all combat and conflict, or even wearing a sword and defending his reputation, for a period of two years.

When he agrees, Velasco finds that he quickly loses his self-respect and the regard of others.

He regains those qualities only when he steps forward as the Queen’s champion, ready to meet the King on the field of honour.

There are tragic stories, stories in which the hero’s fortunes usually begin by rising, but eventually “turn down” to disaster.

(The Greek word catastrophe means literally a “down stroke“, the downturn in the hero’s fortunes at the end of a tragedy.)

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

Before the duel can take place, however, the assembled courtiers protest the proceeding.

Muretto steps forward to explain his role in manipulating Alphonso’s mind.

Finally, Alphonso is convinced of the Queen’s innocence and repents his past harshness.

Their rocky relationship reaches a new tolerance and understanding.

A humbled Salassa also resolves to give up her vain and selfish ways to be a fit wife for Velasco.

There are comedies, stories in which things initially seem to become more and more coomplicated for the hero, until they are entangled in a complete knot, from which there seems to be no escape, but eventually comes the peripeteia, the reversal of fortune.

The knot is miraculously unravelled (from which we get the French word denouement, an “unknotting“.

The hero is liberated.

We and all the world rejoice.

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

The play’s comic relief is supplied by a group of minor characters – two quarrelling followers of Alphonso, the astrologer Pynto and a bluff captain named Bufo, plus Velasco’s servant Mopas and the matchmaker/bawd Madame Shaparoon.

The plot of a story leads its hero either to a catastrophe or to a denouement, to frustration or liberation, to death or a new lease on life.

(The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker)

In ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, Giovanni, recently returned to Parma from university in Bologna, has developed an incestuous passion for his sister Annabella and the play opens with his discussing this ethical problem with Friar Bonaventura.

Bonaventura tries to convince Giovanni that his desires are evil despite Giovanni’s passionate reasoning and eventually persuades him to try to rid himself of his feelings through repentance.

Above: Parma, Italy

“Nice philosophy may tolerate unlikely arguments, but Heaven admits no jest.“

(‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, John Ford)

Annabella, meanwhile, is being approached by a number of suitors including Bergetto, Grimaldi, and Soranzo.

She is not interested in any of them.

Giovanni finally tells her how he feels (obviously having failed in his attempts to repent) and finally wins her over.

Annabella’s tutoress Putana (“Whore“) encourages the relationship.

The siblings consummate their relationship.

“I have spent many a silent night in sighs and groans, ran over all my thoughts, despised my fate, reasoned against the reasons of my love, done all that smoothed-cheek Virtue could advise, but found all bootless:

‘Tis my destiny that you must either love or I must die.“

(‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, John Ford)

Hippolita, a past lover of Soranzo, verbally attacks him, furious with him for letting her send her husband Richardetto on a dangerous journey she believed would result in his death so that they could be together, then declining his vows and abandoning her.

Soranzo leaves and his servant Vasques promises to help Hippolita get revenge on Soranzo and the pair agree to marry after they murder him.

“Delay in vengeance gives a heavier blow.“

(‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, John Ford)

Richardetto is not dead but also in Parma in disguise with his niece Philotis.

Richardetto is also desperate for revenge against Soranzo and convinces Grimaldi that to win Annabella, he should stab Soranzo with a poisoned sword.

Bergetto and Philotis, now betrothed, are planning to marry secretly in the place Richardetto orders Grimaldi to wait.

Grimaldi mistakenly stabs and kills Bergetto instead, leaving Philotis, Poggio (Bergetto’s servant), and Donado (Bergetto’s uncle) distraught.

“There is a place, in a black and hollow vault, where day is never seen.

There shines no sun, but flaming horror of consuming fires – a lightless sulphur, choked with smoky fogs of an infected darkness.

In this place dwell many thousand thousand sundry sorts of never-dying deaths.“

(‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, John Ford)

Annabella resigns herself to marrying Soranzo, knowing she has to marry someone other than her brother.

She subsequently falls ill and it is revealed that she is pregnant.

Friar Bonaventura then persuades her to marry Soranzo before her pregnancy becomes apparent.

Donado and Florio (father of Annabella and Giovanni) go to the Cardinal’s house, where Grimaldi has been in hiding, to beg for justice.

The Cardinal refuses due to Grimaldi’s high status and instead sends him back to Rome.

Florio tells Donado to wait for God to bring them justice.

“Why, I hold fate clasped in my fist and could command the course of Time’s eternal motion, hadst thou been one thought more steady than an ebbing sea.”

(‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, John Ford)

Annabella and Soranzo are married soon after.

Their ceremony includes masque dancers, one of whom reveals herself to be Hippolita.

She claims to be willing to drink a toast with Soranzo and the two raise their glasses and drink, on which note she explains that her plan was to poison his wine.

Vasques comes forward and reveals that he was always loyal to his master and he poisoned Hippolita.

She dies spouting insults and damning prophecies to the newlyweds.

Seeing the effects of anger and revenge, Richardetto abandons his plans and sends Philotis off to a convent to save her soul.

“There’s not a hair sticks on my head but, like a leaden plummet, it sinks me to the grave:

I must creep thither.

The journey is not long.“

(The Broken Heart, John Ford)

When Soranzo discovers Annabella’s pregnancy, the two argue until Annabella realises that Soranzo truly did love her and finds herself consumed with guilt.

She is confined to her room by her husband, who plots with Vasques to avenge himself against his cheating wife and her unknown lover.

On Soranzo’s exit, Putana comes onto the stage and Vasques pretends to befriend her to gain the name of Annabella’s baby’s father.

Once Putana reveals that it is Giovanni, Vasques has bandits tie Putana up and put out her eyes as punishment for the terrible acts she has willingly overseen and encouraged.

In her room, Annabella writes a letter to her brother in her own blood, warning him that Soranzo knows and will soon seek revenge.

The Friar delivers the letter, but Giovanni is too arrogant to believe he can be harmed and ignores advice to decline the invitation to Soranzo’s birthday feast.

The Friar subsequently flees Parma to avoid further involvement in Giovanni’s downfall.

“Love is dead.

Let lovers’ eyes locked in endless dreams, th’ extreme of all extremes, ope no more, for now Love dies.”

(The Broken Heart, John Ford)

On the day of the feast, Giovanni visits Annabella in her room and after talking with her, stabs her during a kiss.

He then enters the feast, at which all remaining characters are present, wielding a dagger on which his sister’s heart is skewered and tells everyone of the incestuous affair.

Florio dies immediately from shock.

Soranzo attacks Giovanni verbally and Giovanni stabs and kills him.

Vasques intervenes, wounding Giovanni before ordering the bandits to finish the job.

Following the massacre, the Cardinal orders Putana to be burnt at the stake, Vasques to be banished, and the Church to seize all the wealth and property belonging to the dead.

Richardetto finally reveals his true identity to Donado and the play ends with the cardinal saying of Annabella:

“Who could not say,

‘Tis pity she’s a whore?“.

“Fly hence, shadows, that do keep,

Watchful sorrows, charmed in sleep.“

(The Lover’s Melancholy, John Ford)

The Lady’s Trial employs the multiple-plot structure that is typical of Ford and common in the dramas of the era.

The main plot concerns Auria, an aristocrat of Genoa, and his marriage to the beautiful and virtuous but lowly-born Spinella.

Auria’s marriage across class lines is controversial among other Genoese nobles, like his friend Aurelio.

When Auria announces that he is going off to the wars against the Turks to repair his fortunes – Spinella brought no dowry – Aurelio opposes the move on two counts:

Spinella will be exposed to temptations.

The role of soldier of fortune is unbecoming to a nobleman.

Auria replies that he trusts his wife and that he would rather stand on his own than depend on his friends.

The contrast is drawn between the two men:

Aurelio is rule-bound and conventional, while Auria is more independent in his judgments.

“He is a noble gentleman; withal

Happy in his endeavours: the general voice

Sounds him for courtesy, behaviour, language,

And every fair demeanour, an example:

Titles of honour add not to his worth;

Who is himself an honour to his title.“

(The Lady’s Trial, John Ford)

Aurelio is right in one respect:

Spinella is exposed to temptation in her husband’s absence.

The nobleman Adurni tries to seduce Spinella, though he is so convincingly repulsed that he reforms and abandons his lustful ways.

Spinella’s reputation is compromised, however, when Aurelio exposes their meeting.

Even when Adurni confesses his transgression and apologizes to the returned husband, the scandal comes to a head in a formal trial of Spinella (“the lady’s trial” of the title).

The trial allows Spinella to exonerate herself and prove to the world, and to aristocratic Genoese society, her honour and virtue.

Auria accepts Adurni’s repentance as sincere and chooses the path of reason over violent retribution.

Adurni in turn takes Spinella’s sister Castanna as his bride, as a seal of their reconciliation.

“Let them fear bondage who are slaves to fear;

The sweetest freedom is an honest heart.”

(The Lady’s Trial, John Ford)

The secondary plot involves the divorced couple Benatzi and Levidolche.

Levidolche has been seduced by Adurni.

Benatzi seeks to catch her in the act by wooing her in disguise — but Levidolche recognizes him and decides to reform.

But she tries to manipulate Benatzi into taking revenge on Adurni — an attempt that fails comically.

“We can drink till all look blue.“

(The Lady’s Trial, John Ford)

The third level, the comic subplot, deals with the Amoretta, a comical young lady with a lisp who has an obsession with horses.

She is pursued by two ridiculous suitors.

Firstly Guzman, a Spanish soldier with breath smelling of garlic and herring and Fulgoso a good looking but rather dim witted Dutchman who whistles constantly.

The two would-be suitors are encouraged by Futelli and Piero for the pairs own amusement.

Through various hilarious failed attempts by the two foreigners, the play is provided some much needed comic relief.

Amoretta eventually marries the vermin-like Futelli.

“A bachelor may thrive by observation, on a little.

A single life’s no burden, but to draw in yokes is chargeable and will require a double maintenance.“

(The Fancies, Chaste and Noble, John Ford)

The play ends with four marriages.

In a pattern typical of the comic genre, everyone has learned his or her lesson.

In Auria, Ford’s portrayal of a husband who “responds rationally to the rumour of his wife’s infidelity” provides a bold departure from, and a stark contrast to, earlier figures in English Renaissance drama like Othello, as well as the precedents of Ford’s own earlier plays.

“Sister, look ye, how, by a new creation of my tailor’s I’ve shook off old mortality.”

(The Fancies, Chaste and Noble, John Ford)

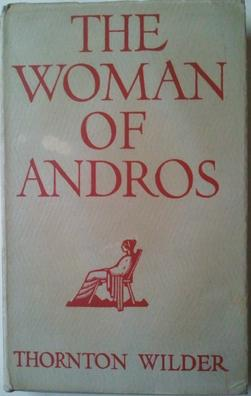

Thornton Niven Wilder (17 April 1897 – 1975) was an American playwright and novelist.

He won three Pulitzer Prizes for the novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey and for the plays Our Town and The Skin of Our Teeth, and a US National Book Award for the novel The Eighth Day.

Above: American writer Thornton Wilder

“We can only be said to be alive in those moments when our hearts are conscious of our treasures.“

(The Woman of Andros, Thornton Wilder)

Wilder began writing plays while at the Thacher School in Ojai, California, where he did not fit in and was teased by classmates as overly intellectual.

According to a classmate:

“We left him alone, just left him alone.

And he would retire at the library, his hideaway, learning to distance himself from humiliation and indifference.”

“Literature is the orchestration of platitudes.“

(TIME magazine, 12 January 1953, Thornton Wilder)

After graduating, Wilder went to Italy and studied archaeology and Italian (1920 –1921) as part of an eight-month residency at the American Academy in Rome.

He then taught French at the Lawrenceville School in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, beginning in 1921.

His first novel, The Cabala, was published in 1926.

In 1927, The Bridge of San Luis Rey brought him commercial success and his first Pulitzer Prize (1928).

He resigned from the Lawrenceville School in 1928.

From 1930 to 1937 he taught at the University of Chicago, during which time he published his translation of André Obey’s own adaptation of the tale “Le Viol de Lucrece” (1931) under the title “Lucrece“.

In Chicago, he became famous as a lecturer and was chronicled on the celebrity pages.

Above: University of Chicago shield

In 1938 he won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama for his play Our Town.

He won the Prize again in 1943 for his play The Skin of Our Teeth.

“Many plays — certainly mine — are like blank checks.

The actors and directors put their own signatures on them.“

(The New York Mirror, 13 July 1956, Thornton Wilder)

Above: Thornton Wilder

He went on to be a visiting professor at Harvard University, where he served for a year as the Charles Eliot Norton professor.

Though he considered himself a teacher first and a writer second, he continued to write all his life, receiving the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 1957 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963.

In 1968 he won the National Book Award for his novel The Eighth Day.

“The most valuable thing I inherited was a temperament that does not revolt against Necessity and that is constantly renewed in Hope.“

(Thornton Wilder)

Above: Frank Kraven as The Stage Manager in Our Town

The Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927) tells the story of several unrelated people who happen to be on a bridge in Peru when it collapses, killing them.

Philosophically, the book explores the question of why unfortunate events occur to people who seem “innocent” or “undeserving“.

It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1928.

In 1998 it was selected by the editorial board of the American Modern Library as one of the 100 best novels of the 20th century.

The book was quoted by British Prime Minister Tony Blair during the memorial service for victims of the September 11 attacks in 2001.

“For my reading I have chosen the final words of The Bridge of San Luis Rey written by Thornton Wilder in 1927.

It is about a tragedy that took place in Peru, when a bridge collapsed over a gorge and five people died.

“A witness to the deaths, wanting to make sense of them and explain the ways of God to his fellow human beings, examined the lives of the people who died, and these words were said by someone who knew the victims, and who had been through the many emotions, and the many stages, of bereavement and loss.

But soon we will die, and all memories of those five will have left Earth, and we ourselves shall be loved for a while and forgotten.

But the love will have been enough.

All those impulses of love return to the love that made them.

Even memory is not necessary for love.

There is a land of the living and a land of the dead, and the bridge is love.

The only survival, the only meaning.“

(The Guardian, Friday 21 September 2001, Tony Blair)

Above: Tony Blair

Since then its popularity has grown enormously.

The book is the progenitor of the modern disaster epic in literature and film-making, where a single disaster intertwines the victims, whose lives are then explored by means of flashbacks to events before the disaster.

The first few pages of the first chapter explain the book’s basic premise:

The story centers on a fictional event that happened in Peru on the road between Lima and Cuzco, at noon on Friday 20 July 1714.

A rope bridge woven by the Inca a century earlier collapsed at that particular moment, while five people were crossing it, sending them falling from a great height to their deaths in the river below.

The collapse was witnessed by Brother Juniper, a Franciscan friar who was on his way to cross the bridge himself.

A deeply pious man who seeks to provide some sort of empirical evidence that might prove to the world God’s Divine Providence, he sets out to interview everyone he can find who knew the five victims.

Over the course of six years, he compiles a huge book of all of the evidence he gathers to show that the beginning and end of a person is all part of God’s plan for that person.

Part One foretells the burning of the book that occurs at the end of the novel, but it also says that one copy of Brother Juniper’s book survives and is at the library of the University of San Marcos, where it now sits neglected.

Part Two focuses on one of the victims of the collapse:

Doña María, the Marquesa de Montemayor.

The daughter of a wealthy cloth merchant, the Marquesa was an ugly child who eventually entered into an arranged marriage and bore a daughter, Clara, whom she loved dearly.

Clara was indifferent to her mother, though, and became engaged to a Spanish man and moved across the ocean to Spain where she married.

Doña María visits her daughter in Spain, but when they cannot get along, she returns to Lima.

The only way that they can communicate comfortably is by letter.

Doña María pours her heart into her writing, which becomes so polished that her letters will be read in schools in the centuries after her lifetime.

“Love is an energy which exists of itself.

It is its own value.“

(TIME magazine, 3 February 1958, Thornton Wilder)

Doña María takes as her companion Pepita, a girl raised at the Convent of Santa María Rosa de las Rosas.

When she learns that her daughter is pregnant in Spain, Doña María decides to make a pilgrimage to the shrine of Santa María de Cluxambuqua to pray that the baby will be healthy and loved.

Pepita goes along as company and to supervise the staff.

When Doña María is out at the shrine, Pepita stays at the inn and writes a letter to her patron, the Abbess María del Pilar, complaining about her misery and loneliness.

Doña María sees the letter on the table when she gets back and reads it.

Later, she asks Pepita about the letter.

Pepita says she tore it up because the letter was not brave.

Doña María has new insight into the ways in which her own life and love for her daughter have lacked bravery.

She writes her “first letter” (actually Letter LVI) of courageous love to her daughter, but two days later, returning to Lima, she and Pepita are on the bridge of San Luis Rey when it collapses.

“Love, though it expends itself in generosity and thoughtfulness, though it gives birth to visions and to great poetry, remains among the sharpest expressions of self-interest.

Not until it has passed through a long servitude, through its own self-hatred, through mockery, through great doubts, can it take its place among the loyalties.”

(Thornton Wilder)

Esteban and Manuel are twins who were left at the Convent of Santa María Rosa de las Rosas as infants.

The Abbess of the convent, Madre María del Pilar, developed a fondness for them as they grew up.

When they became older, they decided to be scribes.

They are so close that they have developed a secret language that only they understand.

Their closeness becomes strained when Manuel falls in love with Camila Perichole, a famous actress.

“Style is but the faintly contemptible vessel in which the bitter liquid is recommended to the world.“

(The Bridge of San Luis Rey, Thornton Wilder)

Perichole flirts with Manuel and swears him to secrecy when she retains him to write letters to her lover, the Viceroy.

Esteban has no idea of their relationship until she turns up at the twins’ room one night in a hurry and has Manuel write to a matador with whom she is having an affair.

Esteban encourages his brother to follow her, but instead Manuel swears that he will never see her again.

Later, Manuel cuts his knee on a piece of metal and it becomes infected.

The surgeon instructs Esteban to put cold compresses on the injury:

The compresses are so painful that Manuel curses Esteban, though he later remembers nothing of his curses.

Esteban offers to send for the Perichole, but Manuel refuses.

Soon after, Manuel dies.

“Now he discovered that secret from which one never quite recovers, that even in the most perfect love one person loves less profoundly than the other.“

(The Bridge of San Luis Rey, Thornton Wilder)

When the Abbess comes to prepare the body, she asks Esteban his name and he says he is Manuel.

Gossip about his ensuing strange behavior spreads all over town.

He goes to the theatre but runs away before the Perichole can talk to him.

The Abbess also tries to talk to him, but he runs away, so she sends for Captain Alvarado.

“Many who have spent a lifetime in it can tell us less of love than the child that lost a dog yesterday.”

(Thornton Wilder)

Captain Alvarado, a well-known sailor and explorer, goes to see Esteban in Cuzco and hires him to sail the world with him, far from Peru.

Esteban agrees, then refuses, then acquiesces if he can get all his pay in advance to buy a present for the Abbess before he departs.

That night Esteban attempts suicide but is saved by Captain Alvarado.

The Captain offers to take him back to Lima to buy the present.

At the ravine spanned by the bridge of San Luis Rey, the Captain goes down to a boat that is ferrying some materials across the water.

Esteban goes to the bridge and is on it when it collapses.

“I am not interested in the ephemeral — such subjects as the adulteries of dentists.

I am interested in those things that repeat and repeat and repeat in the lives of the millions.“

(The New York Times, 6 November 1961, Thornton Wilder)

Uncle Pio acts as Camila Perichole’s valet, and, in addition, “her singing-master, her coiffeur, her masseur, her reader, her errand-boy, her banker.

Rumour added: her father.”

He was born the bastard son of a Madrid aristocrat and later travelled the world engaged in a wide variety of dubious, though legal, businesses, most related to being a go-between or agent of the powerful, including (briefly) conducting interrogations for the Inquisition.

His life “became too complicated” and he fled to Peru.

He came to realize that he had just three interests in the world:

- independence

- the constant presence of beautiful women

- the masterpieces of Spanish literature, particularly those of the theatre

“Like all the rich he could not bring himself to believe that the poor – Look at their houses! Look at their clothes – could really suffer.

Like all the cultivated he believed that only the widely read could be said to know that they were unhappy.“

(The Bridge of San Luis Rey, Thornton Wilder)

He finds work as the confidential agent of the Viceroy of Peru.

One day, he discovers a 12-year-old café singer, Micaela Villegas, and takes her under his protection.

Over the course of years, as they travel from tavern to tavern throughout Latin America, she grows into a beautiful and talented young woman.

Uncle Pio instructs her in the etiquette of high society and goads her to greatness by expressing perpetual disappointment with her performances.

She develops into Camila Perichole, the most honoured actress in Lima.

“99% of the people in the world are fools and the rest of us are in great danger of contagion.“

(The Matchmaker, Thornton Wilder)

After many years of success, the Perichole becomes bored with the stage.

The elderly Viceroy, Don Andrés, takes her as his mistress.

She and Uncle Pio and the Archbishop of Peru and, eventually, Captain Alvarado meet frequently at midnight for dinner at the Viceroy’s mansion.

Through it all, Uncle Pio remains faithfully devoted to her, but as Camila ages and bears three children by the Viceroy she focuses on becoming a lady rather than an actress.

She avoids Uncle Pio.

When he talks to her she tells him to not use her stage name.

“Money is like manure.

It is not worth a thing unless it is spread around encouraging young things to grow.“

(The Matchmaker, Thornton Wilder)

When a smallpox epidemic sweeps through Lima, Camila is disfigured by it.

She takes her young son Don Jaime, who suffers from convulsions, to the country.

Uncle Pio sees her one night trying hopelessly to cover her pockmarked face with powder.

Ashamed, she refuses to ever see him again.

He begs her to allow him to take her son to Lima and teach the boy as he taught her.

Despairing at the turn her life has taken, she reluctantly agrees.

Uncle Pio and Jaime leave the next morning.

They are the 4th and 5th people on the bridge of San Luis Rey when it collapses.

“Physicians are the cobblers, rather the botchers, of men’s bodies.

As the one patches our tattered clothes, so the other solders our diseased flesh.“

(The Lover’s Melancholy, John Ford)

Brother Juniper labors for six years on his book about the bridge collapse, talking to everyone he can find who knew the victims, trying various mathematical formulas to measure spiritual traits, with no results beyond conventionally pious generalizations.

He compiles his huge book of interviews with complete faith in God’s goodness and justice, but a council pronounces his work heretical.

The book and Brother Juniper are publicly burned for their heresy.

“Imagination draws on memory.

Memory and imagination combined can stage a servants’ ball or even write a book, if that’s what they want to do.”

(Theophilus North, Thornton Wilder)

The story then shifts back in time to the day of a funeral service for those who died in the bridge collapse.

The Archbishop, the Viceroy and Captain Alvarado are at the ceremony.

At the Convent of Santa María Rosa de las Rosas, the Abbess feels, having lost Pepita and the twin brothers, that her work to help the poor and infirm will die with her.

A year after the accident, Camila Perichole seeks out the Abbess to ask how she can go on, having lost her son and Uncle Pio.

Camila gains comfort and insight from the Abbess.

It is later revealed she becomes a helper at the Convent.

Later, Doña Clara arrives from Spain, also seeking out the Abbess to speak with her about her mother, the Marquesa de Montemayor.

She is greatly moved by the work of the Abbess in caring for the deaf, the insane and the dying.

The novel ends with the Abbess’ observation:

“There is a land of the living and a land of the dead and the bridge is love, the only survival, the only meaning.“

Wilder wrote Our Town, a popular play (and later film) set in fictional Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire.

It was inspired in part by Dante’s Purgatorio and in part by his friend Gertrude Stein’s novel The Making of Americans.

Above: Italian writer Dante Aligheri (1265 – 1321)

Above: American writer Gertrude Stein (1874 – 1946)

Wilder suffered from writer’s block while writing the final act.

Our Town employs a choric narrator called the Stage Manager and a minimalist set to underscore the human experience.

Wilder himself played the Stage Manager on Broadway for two weeks and later in summer stock productions.

Following the daily lives of the Gibbs and Webb families, as well as the other inhabitants of Grover’s Corners, the play illustrates the importance of the universality of the simple, yet meaningful lives of all people in the world in order to demonstrate the value of appreciating life.

The play won the 1938 Pulitzer Prize.

“Wherever you come near the human race there’s layers and layers of nonsense.”

(Our Town, Thornton Wilder)

The Stage Manager introduces the audience to the small town of Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire and the people living there as a morning begins in the year 1901.

Joe Crowell delivers the paper to Doc Gibbs, Howie Newsome delivers the milk, and the Webb and Gibbs households send their children (Emily and Wally Webb, George and Rebecca Gibbs) off to school on this beautifully simple morning.

Professor Willard speaks to the audience about the history of the town.

Editor Webb speaks to the audience about the town’s socioeconomic status, political and religious demographics, and the accessibility and proliferation, or lack thereof, of culture and art in Grover’s Corners.

The Stage Manager leads us through a series of pivotal moments throughout the afternoon and evening, revealing the characters’ relationships and challenges.

“That’s what it was to be alive.

To move about in a cloud of ignorance.

To go up and down trampling on the feelings of those about you.

To spend and waste time as though you had a million years.

To be always at the mercy of one self-centered passion or another.

Now you know — that’s the happy existence you wanted to go back to.

Ignorance and blindness.“

(Our Town, Thornton Wilder)

It is at this time when we are introduced to Simon Stimson, an organist and choir director at the Congregational Church.

We learn from Mrs. Louella Soames that Simon Stimson is an alcoholic when she, Mrs. Gibbs, and Mrs. Webb stop on the corner after choir practice and “gossip like a bunch of old hens“, according to Doc Gibbs, discussing Simon’s alcoholism.

It seems to be a well known fact amongst everyone in town that Simon Stimson has a problem with alcohol.

All the characters speak to his issue as if they are aware of it and his having “seen a peck of trouble” a phrase repeated by more than one character throughout the show.

While the majority of townsfolk choose to “look the other way“, including the town policeman, Constable Warren, it is Mrs. Gibbs who takes Simon’s struggles with addiction to heart, and has a conversation with her husband, Doc Gibbs, about Simon’s drinking.

“Nurse one vice in your bosom.

Give it the attention it deserves and let your virtues spring up modestly around it.

Then you’ll have the miser who is no liar and the drunkard who is the benefactor of the whole city.“

(The Matchmaker, Thornton Wilder)

Underneath a glowing full moon, Act I ends with siblings George and Rebecca, and Emily gazing out of their respective bedroom windows, enjoying the smell of heliotrope in the “wonderful (or terrible) moonlight” with the self-discovery of Emily and George liking each other, and the realization that they are both straining to grow up in their own way.

“The future author is one who discovers that language, the exploration and manipulation of the resources of language, will serve him in winning through to his way.“

(Thornton Wilder interview, Writers at Work)

The audience is dismissed to the first intermission by the Stage Manager who quips:

“That’s the end of Act I, folks.

You can go and smoke, now.

Those that smoke.”

“I think myself as a fabulist, not a critic.

I realize that every writer is necessarily a critic — that is, each sentence is a skeleton accompanied by enormous activity of rejection and each selection is governed by general principles concerning truth, force, beauty, and so on.

But, as I have just suggested, I believe that the practice of writing consists in more and more relegating all that schematic operation to the subconscious.

The critic that is in every fabulist is like the iceberg — nine-tenths of him is underwater.“

(Thornton Wilder interview, Writers at Work)

Three years have passed.

George and Emily prepare to wed.

The day is filled with stress.

Howie Newsome is delivering milk in the pouring rain while Si Crowell, younger brother of Joe, laments how George’s baseball talents will be squandered.

George pays an awkward visit to his soon-to-be in-laws.

Here, the Stage Manager interrupts the scene and takes the audience back a year, to the end of Emily and George’s junior year.

Emily confronts George about his pride.

Over an ice cream soda, they discuss the future and confess their love for each other.

George decides not to go to college, as he had planned, but to work and eventually take over his uncle’s farm.

In the present, George and Emily say that they are not ready to marry — George to his mother, Emily to her father — but they both calm down and happily go through with the wedding.

“A man looks pretty small at a wedding, George.

All those good women standing shoulder to shoulder, making sure that the knot’s tied in a mighty public way.“

(Our Town, Thornton Wilder)

Nine years have passed.

The Stage Manager, in a lengthy monologue, discusses eternity, focusing attention on the cemetery outside of town and the people who have died since the wedding, including Mrs. Gibbs (pneumonia, while travelling), Wally Webb (burst appendix, while camping), Mrs. Soames and Simon Stimson (suicide by hanging).

Town undertaker Joe Stoddard is introduced, as is a young man named Sam Craig who has returned to Grover’s Corners for his cousin’s funeral.

That cousin is Emily, who died giving birth to her and George’s second child.

Once the funeral ends, Emily emerges to join the dead.

Mrs. Gibbs urges her to forget her life, warning her that being able to see but not interact with her family, all the while knowing what will happen in the future, will cause her too much pain.

Ignoring the warnings of Simon, Mrs. Soames and Mrs. Gibbs, Emily returns to Earth to relive one day, her 12th birthday.

She joyfully watches her parents and some of the people of her childhood for the first time in years, but her joy quickly turns to pain as she realizes how little people appreciate the simple joys of life.

The memory proves too painful for her and she realizes that every moment of life should be treasured.

When she asks the Stage Manager if anyone truly understands the value of life while they live it, he responds:

“No. The saints and poets, maybe – they do some.”

Emily returns to her grave next to Mrs. Gibbs and watches impassively as George kneels weeping over her.

The Stage Manager concludes the play and wishes the audience a good night.

“I can’t.

I can’t go on.

It goes so fast.

We don’t have time to look at one another.

I didn’t realize.

So all that was going on and we never noticed.

Take me back — up the hill — to my grave.

But first:

Wait!

One more look.

Good-bye, Good-bye, world.

Good-bye Grover’s Corners – Mama and Papa.

Good-bye to clocks ticking and Mama’s sunflowers.

And food and coffee.

And new ironed dresses and hot bath and sleeping and waking up.

Oh, Earth, you’re too wonderful for anybody to realize you.

Do human beings ever realize life while they live it?

Every, every minute?

I’m ready to go back.

I should have listened to you.

That’s all human beings are!

Just blind people.“

(Our Town, Thornton Wilder)

His play The Skin of Our Teeth opened in New York on 18 November 1942, featuring Fredric March and Tallulah Bankhead.

Again, the themes are familiar:

- the timeless human condition

- history as progressive, cyclical, or entropic

- literature, philosophy, and religion as the touchstones of civilization

Three acts dramatize the travails of the Antrobus family, allegorizing the alternate history of mankind.

It was claimed by Joseph Campbell and Henry Morton Robinson, authors of A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, that much of the play was the result of unacknowledged borrowing from James Joyce’s last work.

“The comic spirit is given to us in order that we may analyze, weigh and clarify things in us which nettle us, or which we are outgrowing, or trying to reshape.”

(Thornton Wilder interview, Writers at Work)

Act One is an amalgam of early 20th century New Jersey and the dawn of the Ice Age.

The father is inventing things such as the lever, the wheel, the alphabet and multiplication tables.

The family and the entire northeastern US face extinction by a wall of ice moving southward from Canada.

The story is introduced by a narrator and further expanded by the family maid, Sabina.

There are unsettling parallels between the members of the Antrobus family and various characters from the Bible.

In addition, time is compressed and scrambled to such an extent that the refugees who arrive at the Antrobus house seeking food and fire include the Old Testament prophet Moses, the ancient Greek poet Homer, and women who are identified as Muses.

“I hate this play and every word in it.“

(The Skin of Our Teeth, Thornton Wilder)

Act II takes place on the Boardwalk at Atlantic City, New Jersey, where the Antrobuses are present for George’s swearing-in as president of the Ancient and Honorable Order of Mammals, Subdivision Humans.

Sabina is present, also, in the guise of a scheming beauty queen, who tries to steal George’s affection from his wife and family.

The conventioneers are rowdy and party furiously, but there is an undercurrent of foreboding as a fortune teller warns of an impending storm.

The weather soon transforms from summery sunshine to hurricane to deluge.

Gladys and George each attempt their individual rebellions and are brought back into line by the family.

The act ends with the family members reconciled and, paralleling the Biblical story of Noah’s Ark, directing pairs of animals to safety on a large boat where they survive the storm and the end of the world.

“My advice to you is not to inquire why or whither, but just enjoy your ice cream while it is on your plate — that’s my philosophy.“

(The Skin of Our Teeth, Thornton Wilder)

The final act takes place in the ruins of the Antrobuses’ former home.

A devastating war has occurred.

Maggie and Gladys have survived by hiding in a cellar.

When they come out of the cellar we see that Gladys has a baby.

Sabina joins them, “dressed as a Napoleonic camp-follower“.

George has been away at the front lines leading an army.

Henry also fought, on the opposite side, and returns as a general.

The family members discuss the ability of the human race to rebuild and continue after continually destroying itself.

The question is raised:

“Is there any accomplishment or attribute of the human race of enough value that its civilization should be rebuilt?“

The stage manager interrupts the play-within-the-play to explain that several members of their company can’t perform their parts, possibly due to food poisoning (as the actress playing Sabina saw blue mold on the lemon meringue pie at dinner).

The stage manager drafts a janitor, a dresser and other non-actors to fill their parts, which involve quoting philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle to mark the passing of time within the play.

The alternate history action ends where it began, with Sabina dusting the living room and worrying about George’s arrival from the office.

Her final act is to address the audience and turn over the responsibility of continuing the action, or life, to them.

“I have never forgotten for long at a time that living is struggle.

I know that every good and excellent thing in the world stands moment by moment on the razor-edge of danger and must be fought for — whether it is a field, or a home, or a country.“

(The Skin of Our Teeth, Thornton Wilder)

In his novel The Ides of March (1948), Wilder reconstructed the characters and events leading to, and culminating in, the assassination of Julius Caesar.

Above: Roman general / statesman Julius Caesar (100 – 44 BC)

He had met Jean-Paul Sartre on a US lecture tour after the war.

He was under the influence of existentialism, although rejecting its atheist implications.

Above: French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (1905 – 1980)

“Many great writers have been extraordinarily awkward in daily exchange, but the greatest give the impression that their style was nursed by the closest attention to colloquial speech.”

(Thornton Wilder interview, Writers at Work)

In 1962 and 1963, Wilder lived for 20 months in the small town of Douglas, Arizona, apart from family and friends.

There he started his longest novel, The Eighth Day, which went on to win the National Book Award.

According to Harold Augenbraum in 2009, it “attacked the big questions head on, embedded in the story of small-town America“.

“It is only in appearance that time is a river.

It is rather a vast landscape and it is the eye of the beholder that moves.”

(The Eighth Day, Thornton Wilder)

During a weekend gathering of the Ashley and Lansing families, Breckenridge Lansing is shot while the men are practicing shooting.

Townsfolk suspect that Eustacia Lansing, Breckenridge’s wife, and John Ashley were having an affair.

Ashley is tried, convicted, and sentenced to execution.

Miraculously, days before the scheduled execution, he is rescued by mysterious masked men.

He then escapes to Chile, where he assumes the identity of a Canadian named James Tolland and finds work in the copper mining industry.

“Those who are silent, self-effacing and attentive become the recipient of confidences.”

(The Eighth Day, Thornton Wilder)

While Ashley escapes to Chile, his family — left destitute without his income — turns to running a boarding house to make ends meet.

His son, Roger, assumes a fake name and moves to Chicago.

After working a series of odd jobs, Roger makes a name for himself as a writer for a newspaper.

Ashley’s daughter, Lily, also assumes a fake name and becomes a famous singer in Chicago, later moving to New York.

“Hope, like faith, is nothing if it is not courageous.

It is nothing if it is not ridiculous.”

(The Eighth Day, Thornton Wilder)

At the end of the book, it is revealed that a group of Native Americans, one of whom was friends with Roger, is responsible for helping Ashley escape his execution.

The group did this because, after a flood wiped out their local church, Ashley loaned them money to rebuild it.

It is also revealed that Ashley did not kill Lansing.

Lansing’s son George did, because Lansing was becoming violent towards his wife, George’s mother.

George feared for his mother’s safety, and consequently killed his father and then ran away to San Francisco, and later Russia, to work as an actor.

“A sense of humour judges one’s actions and the actions of others from a wider reference and a longer view and finds them incongrous.

It dampens enthusiasm.

It mocks hope.

It pardons shortcomings.

It consoles failure.

It recommends moderation.”

(The Eighth Day, Thornton Wilder)

Though there is a murder mystery in the novel, the main focus of the work is the history of the Ashley and Lansing families.

Wilder muses frequently on the nature of written history throughout the book.

Towards the end, he writes:

“There is only one history.

It began with the creation of man and will come to an end when the last human consciousness is extinguished.

All other beginnings and endings are arbitrary conventions — makeshifts parading as self-sufficient entireties.

The cumbrous shears of the historian cut out a few figures and a brief passage of time from that enormous tapestry.

Above and below the laceration, to the right and left of it, the severed threads protest against the injustice, against the imposture.“

Above: Thornton Wilder

The book concludes with a number of flash-forwards describing the rest of the lives of the characters.

Ashley’s wife, Beata, moves to Los Angeles and starts a boarding house there.

Roger marries one of Lansing’s daughters.

Ashley’s daughter Sophia suffers from dementia and moves into a sanitarium.

Ashley’s daughter Constance becomes a political activist and moves to Japan.

“We do not choose the day of our birth nor may we choose the day of our death, yet choice is the sovereign faculty of the mind.”

(The Eighth Day, Thornton Wilder)

His last novel, Theophilus North, was published in 1973.

It was made into the film Mr. North in 1988.

In 1920s Newport, Rhode Island, Theophilus North is an engaging, multi-talented middle class Yale University graduate who spends the summer catering to the wealthy families of the city.

He becomes the confidant of James McHenry Bosworth, and a tutor and tennis coach to the families’ children.

He also befriends many from the city’s servant class including Henry Simmons, Amelia Cranston and Sally Boffin.

“Man is not an end but a beginning.

We are at the beginning of the second week.

We are the children of the eighth day.”

(The Eighth Day, Thornton Wilder)

Complications arise when some residents begin to ascribe healing powers to the static electricity shocks that Mr. North happens to generate frequently.

Despite never claiming any healing or medical abilities, he is accused of quackery and with the help of those he had befriended must defend himself.

In the end, Mr. North accepts a position of leadership at an educational and philosophical academy founded by Mr. Bosworth and begins a romance with Bosworth’s granddaughter Persis.

“When God loves a creature he wants the creature to know the highest happiness and the deepest misery.

He wants him to know all that being alive can bring.

That is His best gift.

There is no happiness save in understanding the whole.”

(The Eighth Day, Thornton Wilder)

Donald Richie (17 April 1924 – 2013) was an American-born author who wrote about the Japanese people, the culture of Japan and, especially, Japanese cinema.

Richie was a prolific author.

Above: Donald Richie