Landschlacht, Switzerland, Saturday 2 May 2020 (Lockdown Day #47)

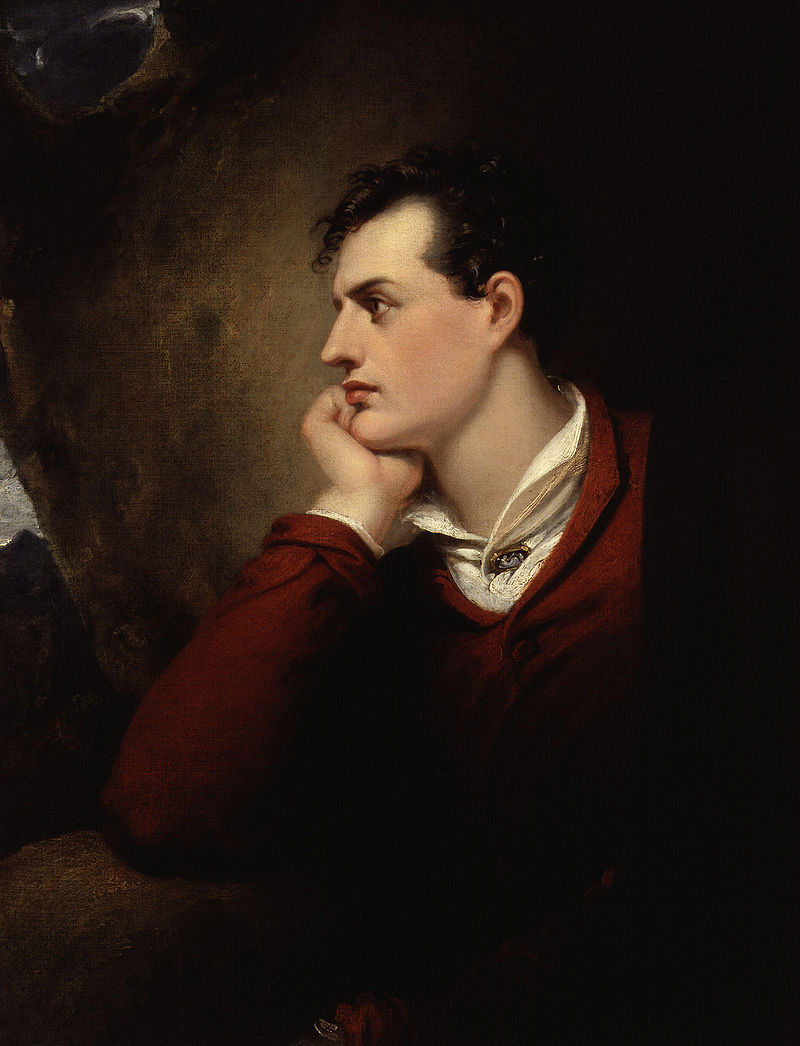

Easter, 1916 is a poem by W. B. Yeats describing the poet’s torn emotions regarding the events of the Easter Rising staged in Ireland against British rule on Easter Monday 24 April 1916.

The uprising was unsuccessful and most of the Irish republican leaders involved were executed for treason.

The poem was written between May and September 1916, but first published in 1921 in the collection Michael Robartes and the Dancer.

Even though a committed nationalist, Yeats usually rejected violence as a means to secure Irish independence, and as a result had strained relations with some of the figures who eventually led the uprising.

The deaths of these revolutionary figures at the hands of the British, however, was as much a shock to Yeats as it was to ordinary Irish people at the time, who did not expect the events to take such a bad turn so soon.

Yeats was working through his feelings about the revolutionary movement in this poem, and the insistent refrain that “a terrible beauty is born” turned out to be prescient, as the execution of the leaders of the Easter Rising by the British had the opposite effect to that intended.

The killings led to a reinvigoration of the Irish Republican movement rather than its dissipation.

An independent Ireland was a needed and beautiful thing, but it came at a terrible Price.

Because it came at a terrible price, freedom was and remains a precious and beautiful thing worth understanding, worth remembering, worth preserving.

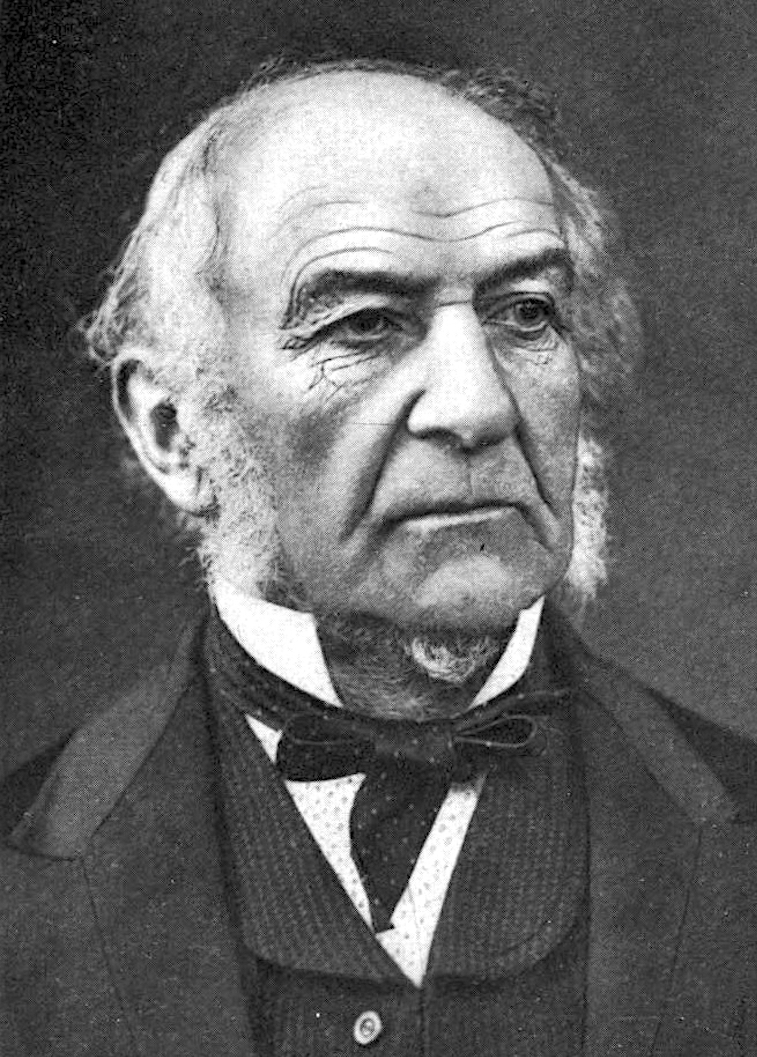

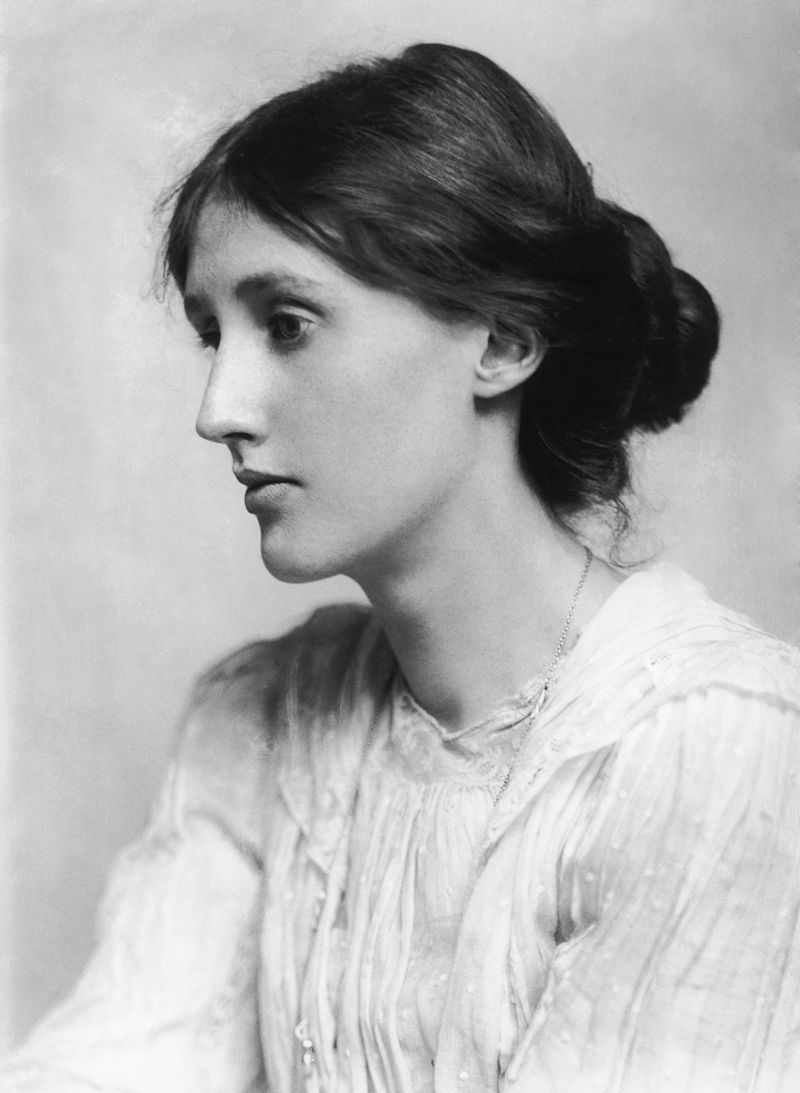

Above: William Butler Yeats (1865 – 1939)

This idea of beauty emerging out of ugliness, of something positive reborn from something horrific, of a quiet and ceaseless survival regardless of what occurs, sums up somewhat both these days of lockdown in much of Switzerland that is still ongoing, and a visit a few years ago to an oasis where one should not be in the heart of the great metropolis of London.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

The disease was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of China’s Hubei province, and has since spread globally, resulting in the ongoing 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic.

As of 29 April 2020, more than 3.11 million cases have been reported across 185 countries and territories, resulting in more than 217,000 deaths.

More than 932,000 people have recovered.

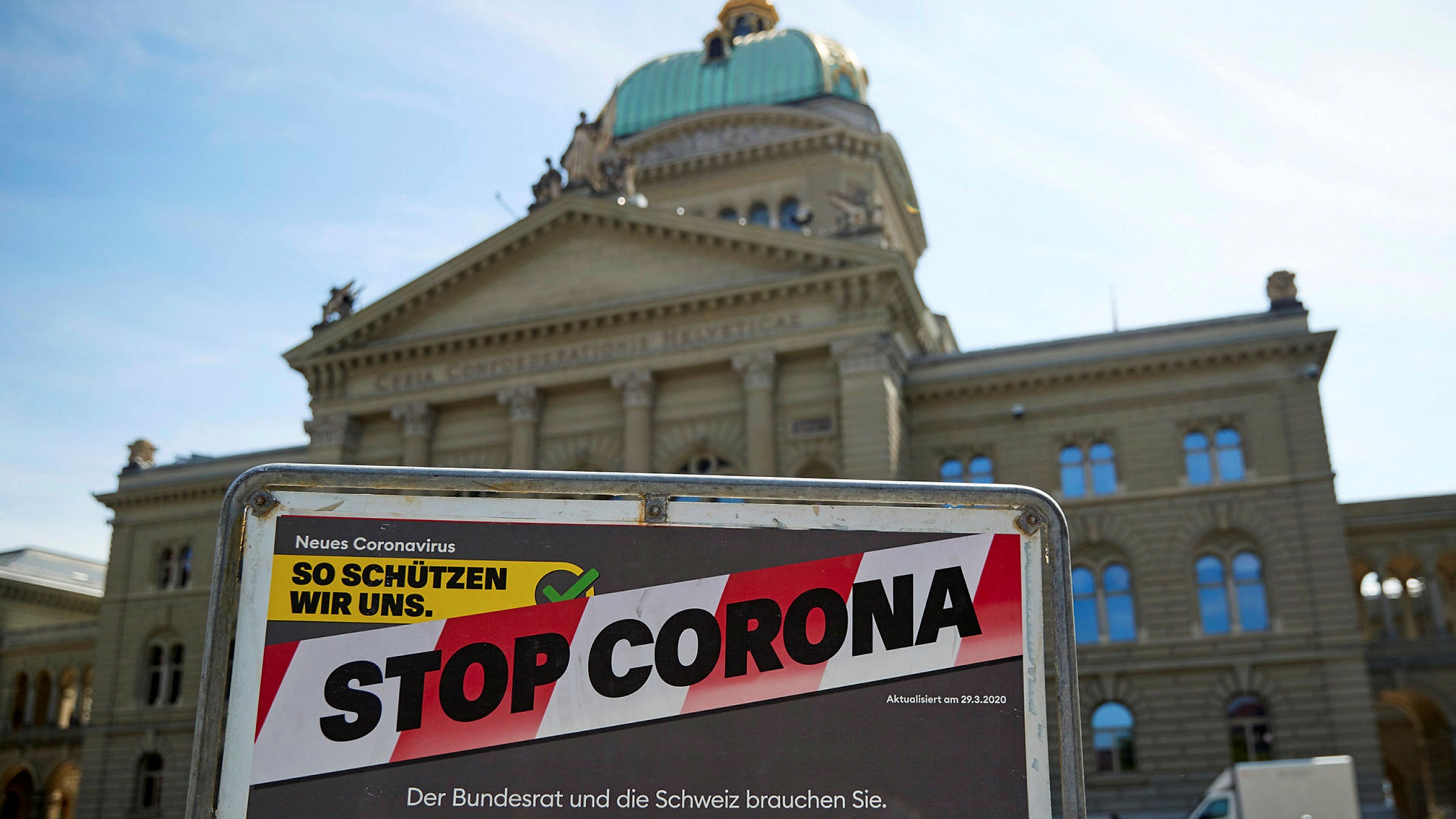

The 2019–2020 coronavirus pandemic was confirmed to have spread to Switzerland on 25 February 2020 when the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed following a COVID-19 outbreak in Italy.

A 70-year-old man in the Italian-speaking canton of Ticino which borders Italy, tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

The man had previously visited Milan.

Afterwards, multiple cases related to the Italy clusters were discovered in multiple cantons, including Basel-City, Zürich and Graubünden.

Multiple isolated cases not related to the Italy clusters were also subsequently confirmed.

On 28 February, the national government, the Federal Council, banned all events with more than 1,000 participants.

On 16 March, schools and most shops were closed nationwide, and on 20 March, all gatherings of more than five people in public spaces were banned.

Additionally, the government gradually imposed restrictions on border crossings and announced economic support measures worth 40 billion Swiss francs.

As well, the Federal Council announced further measures, and a revised ordinance.

Measures include the closure of bars, shops and other gathering places until 19 April, but leaves open certain essentials, such as grocery shops, pharmacies, (a reduced) public transport and the postal service.

The government announced a 42 billion CHF rescue package for the economy, which includes money to replace lost wages for employed and self-employed people, short-term loans to businesses, delay for payments to the government, and support for cultural and sport organizations.

On 20 March, the government announced that no lockdown would be implemented, but all events or meetings over five people were prohibited.

Economic activities would continue including construction.

Those measures were prolonged until 26 April 2020.

On 16 April 2020, Switzerland announced that the country will ease restrictions in a three-step, gradual way.

The first step will begin on 27 April, for those who work in close contact with others, but not in large numbers.

Surgeons, dentists, day care workers, hairdressers, massage and beauty salons can be opened with safety procedures applied.

DIY stores, garden centres, florists and food shops that also sell other goods can also be opened.

The second step will begin on 11 May, assuming the first step is implemented without problems, at which time other shops and schools can be opened.

The third step begin on 8 June with the easing of restrictions on gastronomy, vocational schools, universities, museums, zoos and libraries.

Since St. Patrick’s Day 2020, I have been, for the most part, housebound, with no real place to go, no borders to cross, no planes to catch, no books to buy or borrow, no workplace to work at.

(My wife has been more fortunate in that she is a medical doctor so her services are not only wanted but crucial.)

With nowhere to go, planes are grounded and highways have less traffic than they once did and trains ride the rails half empty.

We are in lockdown because it is believed that we can “flatten the curve” and reduce the numbers of people getting infected by the pandemic.

People are sick, some are dying or have died, hospitals are full and people have become paranoid about social distancing and germ transmission – the more cases in a canton, the more extreme the caution.

These are dark days and times that try a man’s temperament, but there is an upside to all of this.

The worldwide disruption caused due to the 2019–20 corona virus pandemic has resulted in numerous impacts on the environment and the climate.

The severe decline in planned travel has caused many regions to experience a drop in air pollution.

In China, lockdowns and other measures resulted in a 25% reduction in carbon emissions, which one Earth systems scientist estimated may have saved at least 77,000 lives over two months.

However, the outbreak has also disrupted environmental diplomacy efforts, including causing the postponement of the 2020 United Nations Climate Change Conference, and the economic fallout from it is predicted to slow investment in green energy technologies.

Up to 2020, increases in the amount of greenhouse gases produced since the beginning of the industrialization epoch caused average global temperatures on the Earth to rise, causing effects including the melting of glaciers and rising sea levels.

In various forms, human activity caused environmental degradation, an anthropogenic impact.

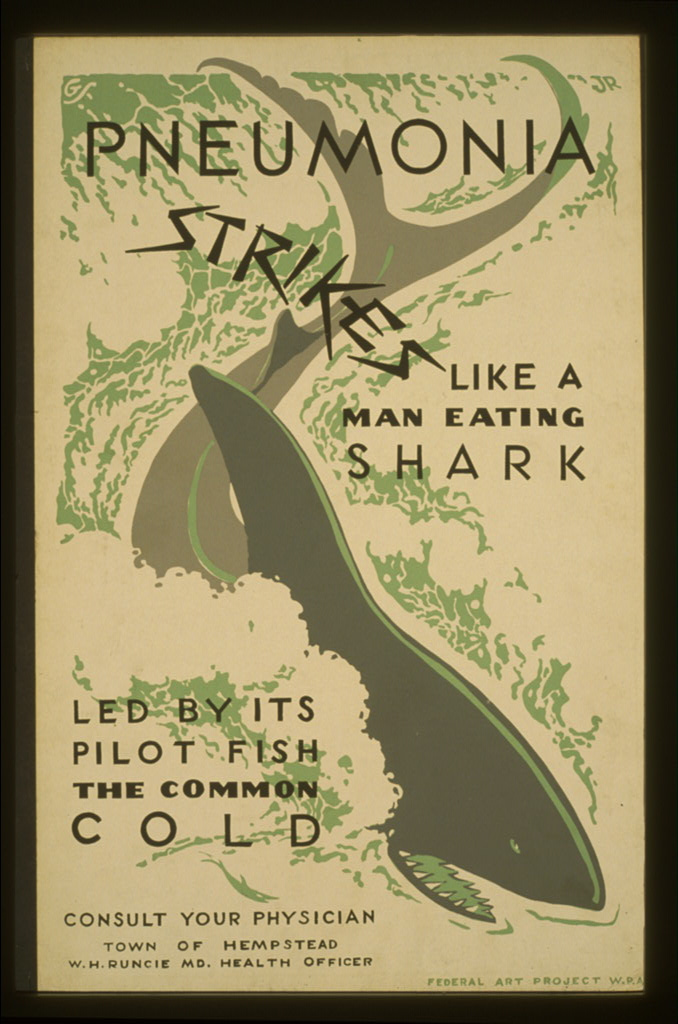

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, measures that were expected to be recommended to health authorities in the case of a pandemic included quarantines and social distancing.

Independently, also prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers argued that reduced economic activity would help decrease global warming, air and marine pollution, allowing the environment to slowly flourish.

Due to the corona virus outbreak’s impact on travel and industry, many regions experienced a drop in air pollution.

Reducing air pollution can reduce both climate change and COVID-19 risks but it is not yet clear which types of air pollution (if any) are common risks to both climate change and COVID-19.

Above: Schematic drawing, causes and effects of air pollution: (1) greenhouse effect, (2) particulate contamination, (3) increased UV radiation, (4) acid rain, (5) increased ground-level ozone concentration, (6) increased levels of nitrogen oxides.

The Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air reported that methods to contain the spread of the corona virus, such as quarantines and travel bans, resulted in a 25% reduction of carbon emission in China.

In the first month of lockdowns, China produced approximately 200 million fewer metric tons of carbon dioxide than the same period in 2019, due to the reduction in air traffic, oil refining, and coal consumption.

As aforementioned, one Earth systems scientist estimated that this reduction may have saved at least 77,000 lives.

However, Sarah Ladislaw from the Center for Strategic & International Studies argued that reductions in emissions due to economic downturns should not be seen as beneficial, stating that China’s attempts to return to previous rates of growth amidst trade wars and supply chain disruptions in the energy market will worsen its environmental impact.

Between 1 January and 11 March 2020, the European Space Agency observed a marked decline in nitrous oxide emissions from cars, power plants and factories in the Po Valley region in northern Italy, coinciding with lockdowns in the region.

The reduction in motor vehicle traffic has led to a drop in air pollution levels.

NASA and ESA have been monitoring how the nitrogen dioxide gases dropped significantly during the initial Chinese phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The economic slowdown from the virus drastically dropped pollution levels, especially in cities like Wuhan, China by 25%.

NASA uses a ozone monitoring instrument (OMI) to analyze and observe the ozone layer and pollutants such as NO2, aerosols and others.

This instrument helped NASA to process and interpret the data coming in due to the lockdowns worldwide.

According to NASA scientists, the drop in NO2 pollution began in Wuhan, China and slowly spread to the rest of the world.

The drop was also very drastic because the virus coincided with the same time of year as the lunar year celebrations in China.

For this festival, factories and businesses close for the last week of January to celebrate the lunar year festival.

The drop in NO2 in China did not achieve an air quality of the standard considered acceptable by health authorities.

Other pollutants in the air such as aerosol emissions remained.

In Venice, the water in the canals cleared and experienced greater water flow and visibility of fish.

The Venice mayor’s office clarified that the increase in water clarity was due to the settling of sediment that is disturbed by boat traffic and mentioned the decrease in air pollution along the waterways.

Demand for fish and fish prices have both decreased due to the pandemic,and fishing fleets around the world sit mostly idle.

Rainer Froese has said the fish biomass will increase due to the sharp decline in fishing and projected that in European waters, some fish such as herring could double their biomass.

As of April 2020, signs of aquatic recovery remain mostly anecdotal.

Nature is returning, but it took a pandemic to make this terrible beauty possible.

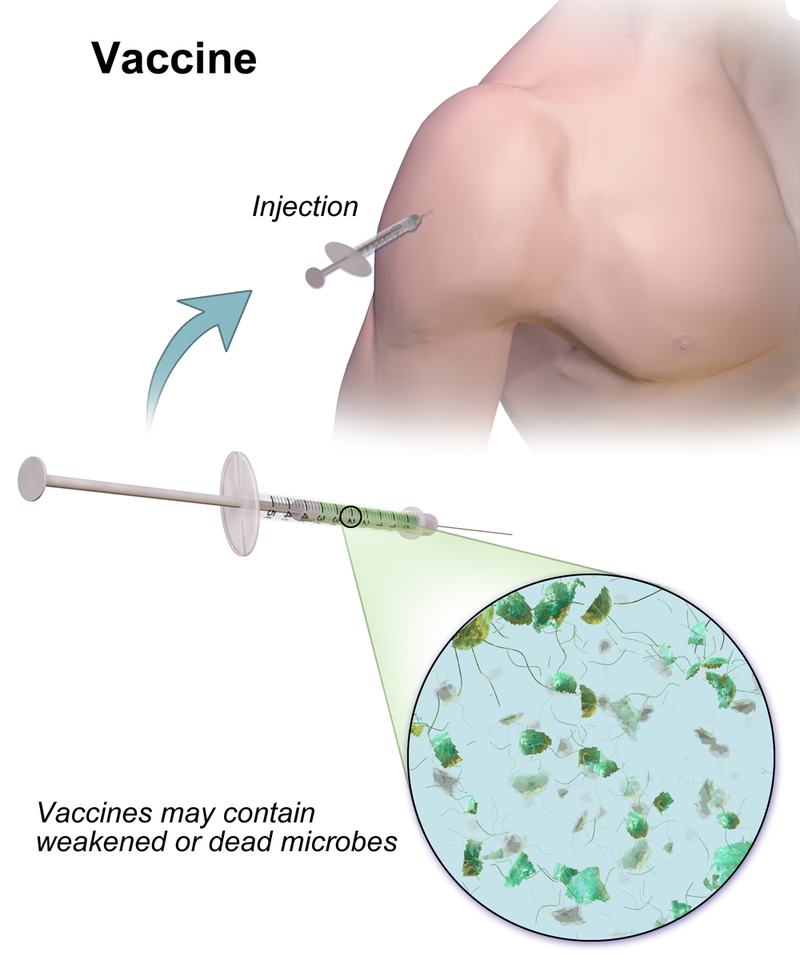

A COVID-19 vaccine is a hypothetical vaccine against corona virus disease 2019 (COVID‑19).

Although no vaccine has completed clinical trials, there are multiple attempts in progress to develop such a vaccine.

In late February 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) said it did not expect a vaccine against severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative virus, to become available in less than 18 months.

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) – which is organizing a US $2 billion worldwide fund for rapid investment and development of vaccine candidates – indicated in April that a vaccine may be available under emergency use protocols in less than 12 months or by early 2021.

|

|

|---|---|

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease.

A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe, its toxins, or one of its surface proteins.

The agent stimulates the body’s immune system to recognize the agent as a threat, destroy it, and to further recognize and destroy any of the microorganisms associated with that agent that it may encounter in the future.

Vaccines can be prophylactic (to prevent or ameliorate the effects of a future infection by a natural or “wild” pathogen), or therapeutic (e.g., vaccines against cancer, which are being investigated).

The administration of vaccines is called vaccination.

Vaccination is the most effective method of preventing infectious diseases.

Widespread immunity due to vaccination is largely responsible for the worldwide eradication of smallpox and the restriction of diseases such as polio, measles and tetanus from much of the world.

Above: Jonas Salk at the University of Pittsburgh where he developed the first polio vaccine

The effectiveness of vaccination has been widely studied and verified.

For example, vaccines that have proven effective include the influenza vaccine, the HPV vaccine and the chicken pox vaccine.

Above: A child with measles, a vaccine-preventable disease

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that licensed vaccines are currently available for twenty-five different preventable infections.

The terms vaccine and vaccination are derived from Variolae vaccinae (smallpox of the cow), the term devised by Edward Jenner to denote cowpox.

He used it in 1798 in the long title of his Inquiry into the Variolae vaccinae Known as the Cow Pox, in which he described the protective effect of cowpox against smallpox.

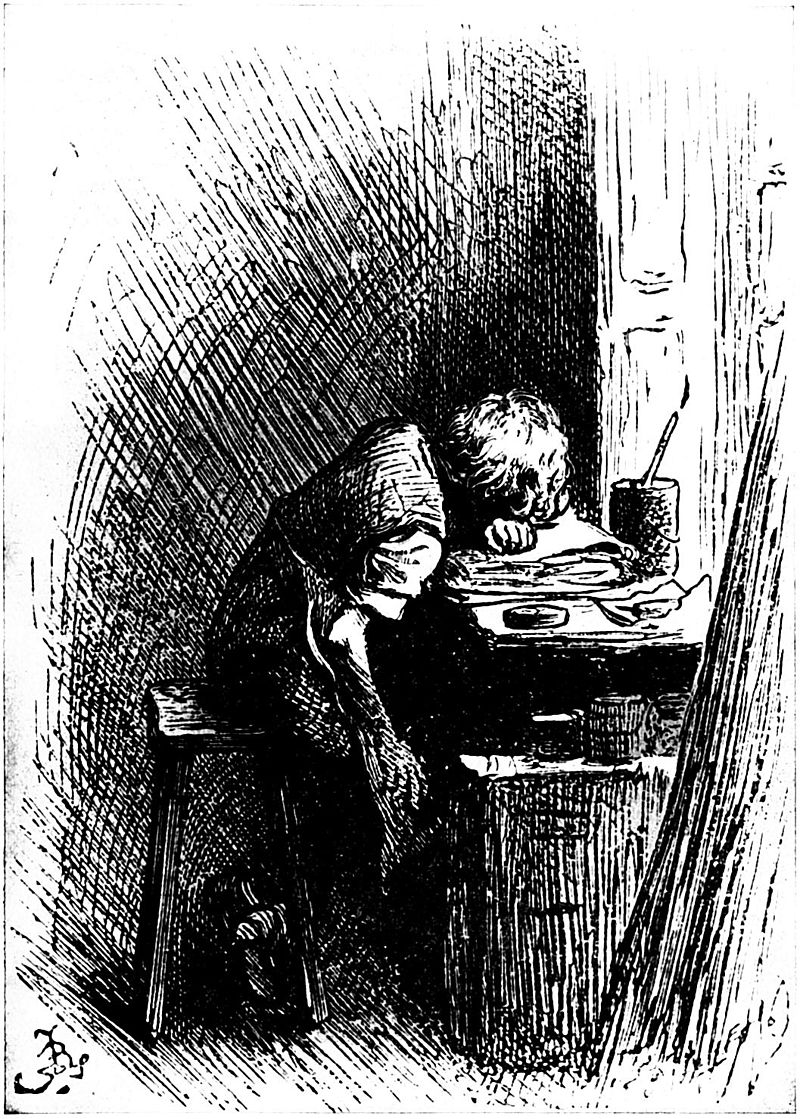

Above: Jenner’s handwritten draft of the first vaccination

In 1881, to honor Jenner, Louis Pasteur (1822 – 1895) proposed that the terms should be extended to cover the new protective inoculations then being developed.

If (and this is a big IF) I understand the concept of vaccines and vaccinations at all, it is necessary to somehow find microbes that can invade a body, inducing its immune system to fight them by releasing antibodies.

After infection, the immune system “remembers” those microbes and if it encounters them again it quickly produces antibodies to prevent the body from attack.

Vaccination induces immunity artificially by imitating an infection, but without causing illness.

An essential part of modern medicine, vaccines have been developed against many dangerous infectious diseases.

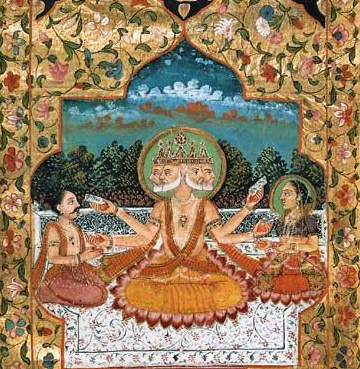

It was widely known in ancient times that the body develops natural resistance to diseases.

The earliest attempts to induce immunity artificially may date back more than 2,000 years in India, but the idea of vaccination as an established legitimate treatment did not rise to popular consciousness until Edward Jenner.

Above: Edward Jenner (1749 – 1823)

Jenner was a successful country physician-surgeon in Berkeley, Southwest England, as well as a talented naturalist.

He had undergone variolation – wherein an infection is rubbed into cuts in the skin of an uninfected person – in his youth, which had made him ill for a time.

As a country doctor, Jenner was aware of the common belief that catching cowpox somehow gave protection against smallpox.

Very few milkmaids and cattle herdsmen seemed to suffer from the latter.

In 1798, Jenner published An Enquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae: A Disease Discovered in Some of the Western Counties of England, Particularly Gloucestershire, and Known by the Name of the Cow Pox, which described his treatment of 23 patients by first vaccinating them with cowpox material and then giving them smallpox.

He noted that after the cowpox vaccine his patients did not catch smallpox.

Above: Jenner’s discovery of the link between cowpox pus and smallpox in humans helped him to create the smallpox vaccine

So, in essence, researchers are looking for a similar solution.

They need to discover the source of the original outbreak, develop a variant of the virus and hope that it builds an immunity to the particular corona virus that plagues the planet at present.

This will take a lot of time, effort and money.

The smallpox vaccine did not come from herbal remedies or old wives’ recipes of certain food or drink, but from a variation of the disease itself.

But nevertheless it was partially the role of Jenner as naturalist – a man who studies nature – I believe to be beneficial in defeating and eradicating this infamous disease in history.

Smallpox has featured in all of recorded history, killed billions and inflicted lasting suffering on billions more.

By studying nature Jenner became a legend in the field of medicine.

Above: This young girl in Bangladesh was infected with smallpox in 1973.

Freedom from smallpox was declared in Bangladesh in December, 1977 when a WHO International Commission officially certified that smallpox had been eradicated from that country.

The ability of viruses to cause devastating epidemics in human societies has led to the concern that viruses could be weaponised for biological warfare.

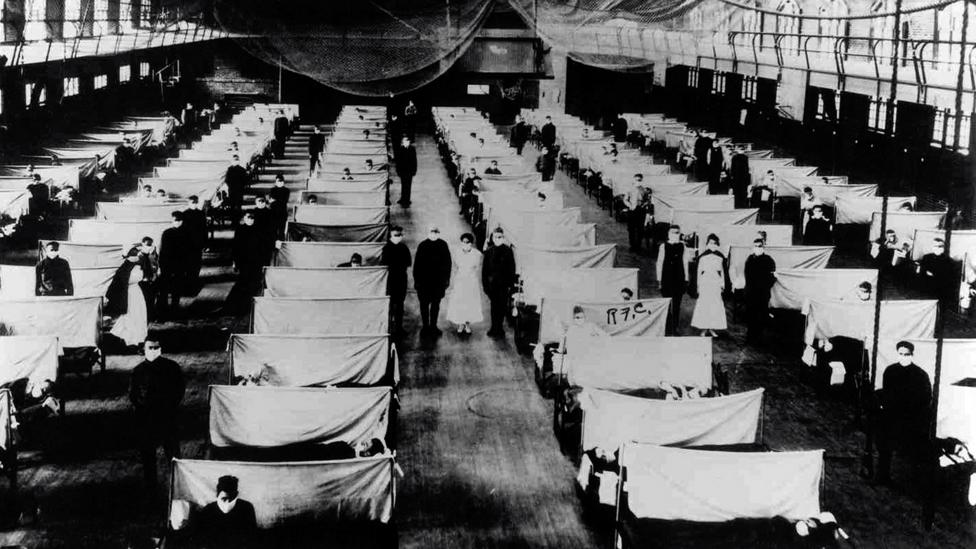

Further concern was raised by the successful recreation of the infamous 1918 influenza virus in a laboratory.

Smallpox virus devastated numerous societies throughout history before its eradication.

There are only two centres in the world authorised by the WHO to keep stocks of smallpox virus: the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR in Russia and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States.

It may be used as a weapon, as the vaccine for smallpox sometimes had severe side-effects, it is no longer used routinely in any country.

Thus, much of the modern human population has almost no established resistance to smallpox and would be vulnerable to the virus.

The corona virus is primarily spread between people during close contact, often via small droplets produced by coughing, sneezing, or talking.

The droplets usually fall to the ground or onto surfaces rather than remaining in the air over long distances.

People may also become infected by touching a contaminated surface and then touching their face.

In experimental settings, the virus may survive on surfaces for up to 72 hours.

It is most contagious during the first three days after the onset of symptoms, although spread may be possible before symptoms appear and in later stages of the disease.

In the case of the corona virus, it is suspected that the virus is zoonotic in nature – that it may have travelled from animal to man.

The question then is:

How did the animal that first infected a person itself get infected?

But where did the first animal catch the disease?

Above: Possibilities for zoonotic disease transmissions

Some scientists speculate that animals catch viruses by eating – perhaps food fouled by other animal feces.

So, an examination of the animals around Wuhan and their diet might give us a better notion of what caused the virus in them and perhaps offer a partial solution towards its prevention.

Imagine a cave of bats and one bat infected one farmer and the farmer took the disease to Wuhan.

Where did the bat catch the virus?

Was only the one bat infected?

If so,why?

Was it something it ate?

It is through the study of both plant and animal life (flora and fauna) that mankind has learned much about medicine as well as the causes and cures of disease.

The profession of apothecary – the formulation and dispensation of drugs to the sick – dates back to at least 2500 BC.

Skilled medics in their own right, apothecaries prepared medical remedies with herbs stored on their own premises.

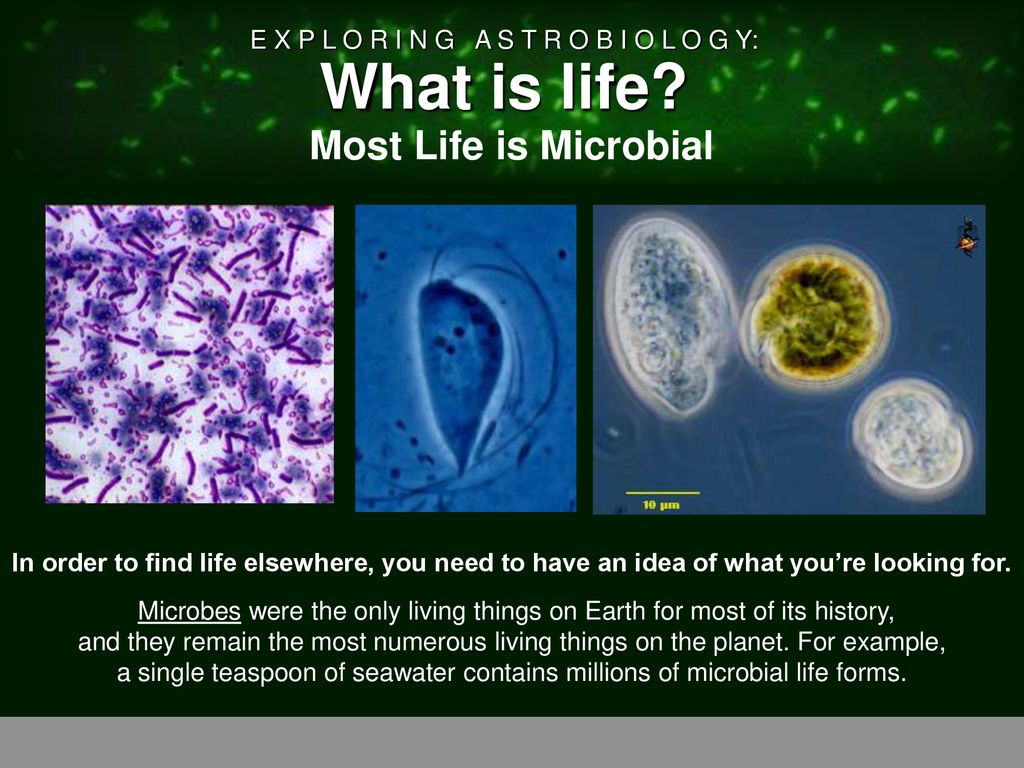

We must be careful to distinguish what a virus is.

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism.

Viruses can infect all types of life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky’s 1892 article describing a non-bacterial pathogen infecting tobacco plants, and the discovery of the tobacco mosaic virus by Martinus Beijerinck (1851 – 1931) in 1898, more than 6,000 virus species have been described in detail, of the millions of types of viruses in the environment.

Viruses are found in almost every ecosystem on Earth and are the most numerous type of biological entity.

The study of viruses is known as virology, a subspeciality of microbiology.

When infected, a host cell is forced to rapidly produce thousands of identical copies of the original virus.

When not inside an infected cell or in the process of infecting a cell, viruses exist in the form of independent particles, or virions, consisting of:

(i) the genetic material, i.e. long molecules of DNA or RNA that encode the structure of the proteins by which the virus acts

(ii) a protein coat, the capsid, which surrounds and protects the genetic material

and in some cases

(iii) an outside envelope of lipids.

The shapes of these virus particles range from simple helical and icosahedral forms to more complex structures.

Most virus species have virions too small to be seen with an optical microscope as they are one hundredth the size of most bacteria.

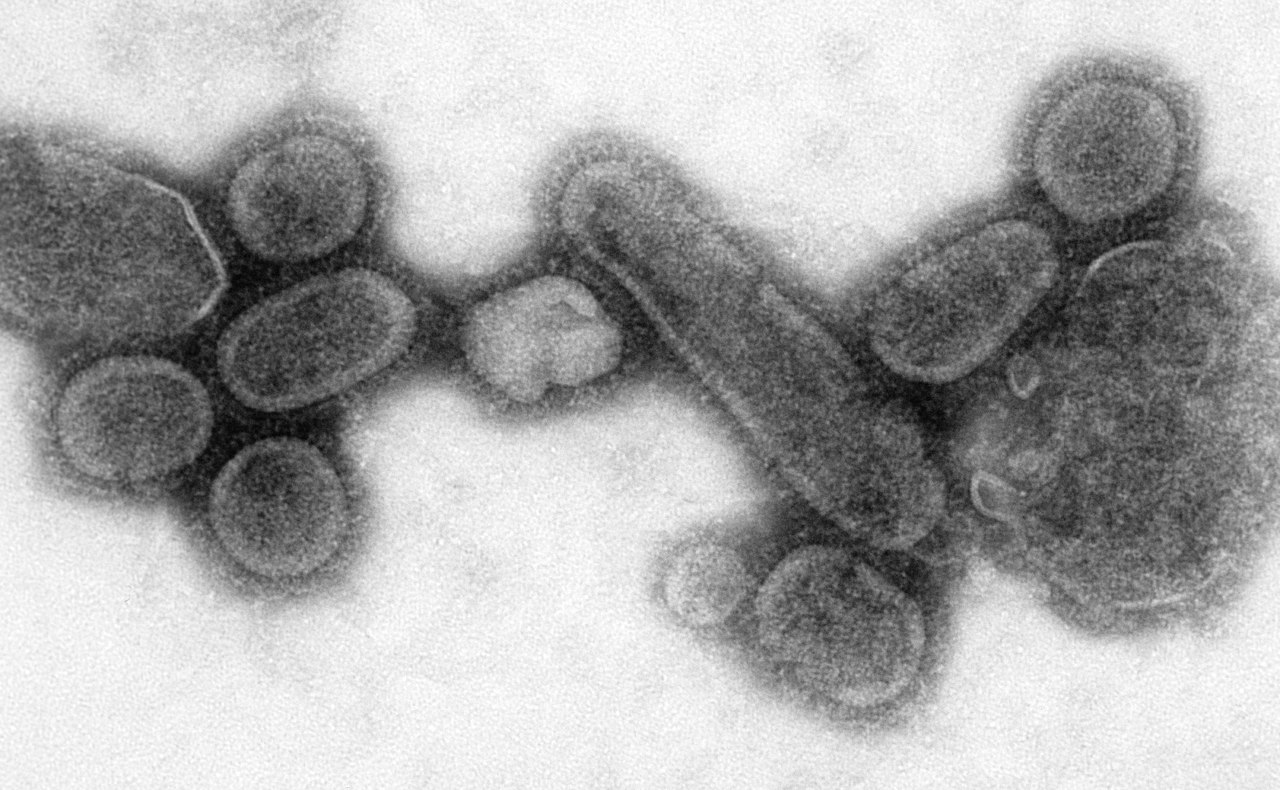

Above: Transmission electron microscope image of a recreated 1918 influenza virus

This negative stained transmission electron micrograph (TEM) showed recreated 1918 influenza virions that were collected from the supernatant of a 1918-infected Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cell culture 18 hours after infection.

In order to sequester these virions, the MDCK cells were spun down (centrifugation), and the 1918 virus present in the fluid was immediately fixed for negative staining.

Dr. Terrence Tumpey, one of the organization’s staff microbiologists and a member of the National Center for Infectious Diseases (NCID), recreated the 1918 influenza virus in order to identify the characteristics that made this organism such a deadly pathogen.

Research efforts such as this enables researchers to develop new vaccines and treatments for future pandemic influenza viruses.

The 1918 Spanish flu epidemic was caused by an influenza A (H1N1) virus, killing more than 500,000 people in the United States and up to 50 million worldwide.

The possible source was a newly emerged virus from a swine or an avian host of a mutated H1N1 virus.

Many people died within the first few days after infection and others died of complications later.

Nearly half of those who died were young, healthy adults.

Influenza A (H1N1) viruses still circulate today after being introduced again into the human population in the 1970s.

The origins of viruses in the evolutionary history of life are unclear:

Some may have evolved from plasmids—pieces of DNA that can move between cells—while others may have evolved from bacteria.

In evolution, viruses are an important means of horizontal gene transfer, which increases genetic diversity in a way analogous to sexual reproduction.

Viruses are considered by some biologists to be a life form, because they carry genetic material, reproduce, and evolve through natural selection, although they lack key characteristics (such as cell structure) that are generally considered necessary to count as life.

Because they possess some but not all such qualities, viruses have been described as “organisms at the edge of life” and as replicators.

Viruses are the most abundant biological entity in aquatic environments.

There are about ten million of them in a teaspoon of seawater.

The corona virus is described as novel, because we ain’t seen nothing like it before.

Viruses spread in many ways.

One transmission pathway is through disease-bearing organisms known as vectors:

For example, viruses are often transmitted from plant to plant by insects that feed on plant sap, such as aphids.

Viruses in animals can be carried by blood-sucking insects.

Influenza viruses (which the corona virus is) are spread by coughing and sneezing.

Norovirus and rotavirus, common causes of viral Gastroenteritis (stomach flu), are transmitted by the faecal–oral route, passed by contact and entering the body in food or water.

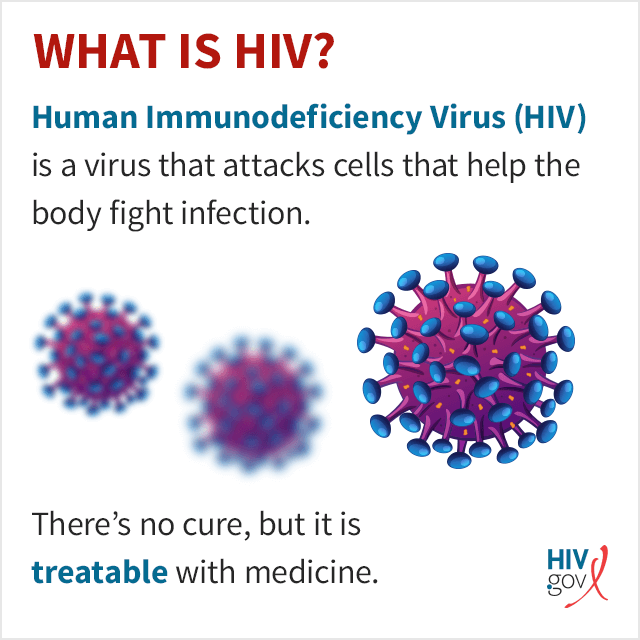

HIV is one of several viruses transmitted through sexual contact and by exposure to infected blood.

The variety of host cells that a virus can infect is called its “host range“.

This means a virus is capable of infecting a few species or many.

Viral infections in animals provoke an immune response that usually eliminates the infecting virus.

Immune responses can also be produced by vaccines, which confer an artificially acquired immunity to the specific viral infection.

Some viruses, including those that cause AIDS, HPV infection, and viral hepatitis, evade these immune responses and result in chronic infections.

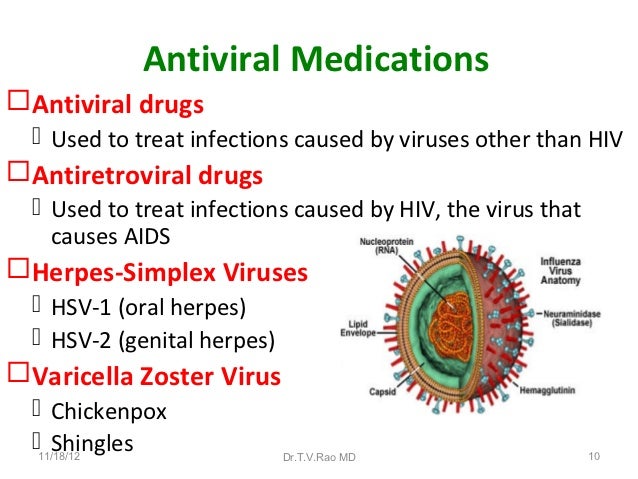

Several antiviral drugs have been developed.

Antiviral drugs are a class of medication used for treating viral infections.

Most antivirals target specific viruses, while a broad-spectrum antiviral is effective against a wide range of viruses.

Unlike most antibiotics, antiviral drugs do not destroy their target pathogen.

Instead they inhibit their development.

Antiviral drugs are one class of antimicrobials, a larger group which also includes antibiotic (also termed antibacterial), antifungal and antiparasitic drugs, or antiviral drugs based on monoclonal antibodies (aka the Jenner method).

Most antivirals are considered relatively harmless to the host, and therefore can be used to treat infections.

They should be distinguished from viricides, which are not medication, but deactivate or destroy virus particles, either inside or outside the body.

Natural viricides are produced by some plants, such as eucalyptus and Australian tea trees.

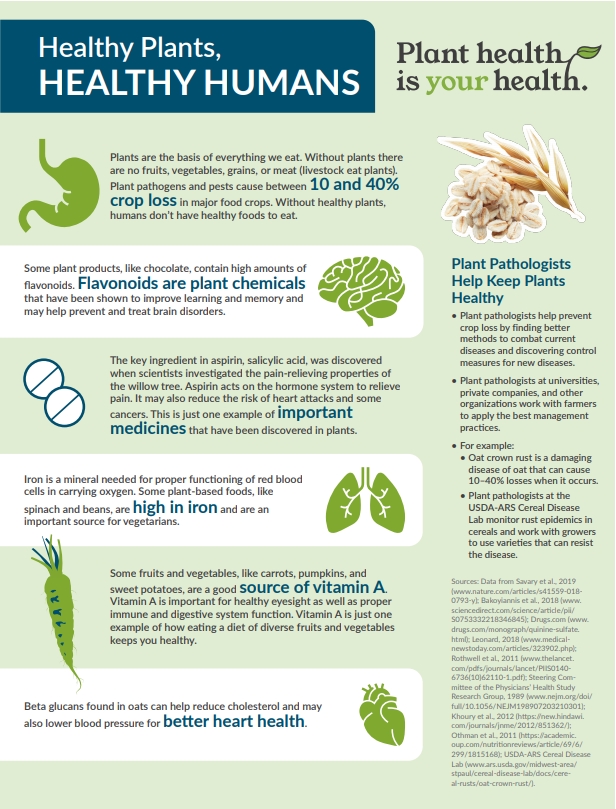

So, as important as it is to find – and find it fast – a vaccine to combat this virus using the virus against itself, I think it is also a good idea – afterwards or concurrently – if greater study of plant life is done to prevent and treat viruses of this and other types.

What if we could identify infected plants?

What if we could find plants that help fight viruses along with vaccines?

Let me frank.

I am no botanist, chemist, or any type of scientist, no farmer or even florist.

For me, generally a plant is edible or inedible, functional or decorative.

I eat fruit and vegetables.

I eat animals that eat fruit and vegetables.

I see trees and lawns and flowerpots from my window.

I see wildflowers and farmers fields and orchards during my daily walks.

When florists resume business I shall occasionally buy my wife a floral arrangement, either as a curative against some stupidity I have done or as a preventative to avoid drama during an emotional time in her life.

I do this for myself as much as for her!

It would be a lie to suggest that I give flora the full attention, respect and praise that it is due.

But for one moment on one vacation when my wife brought me to London to play tourist while she mostly attended a medical conference, I began to consider an amazing universe I had previously ignored.

London, England, Thursday 26 October 2017

The world continued to circle the sun and men do what men do wherever they may be found.

While my wife was attending her medical conference and I was exploring the city on my own…..

Meanwhile:

- Twitter banned all ads from Russian news agencies RT and Sputnik, based on US intelligence’s conclusion that both attempted to interfere with the 2016 US presidential election on behalf of the Russian government.

- An explosion in a fireworks plant, located west of the Indonesian capital Jakarta killed at least 47 and injured 35.

- Four people (three military conscripts and a train passenger) were killed and four conscripts injured after a passenger train collided with an off-road military truck in Raseborg, Finland.

- A Russian Mi-8 helicopter crashed into the sea off Svalbard with eight people reported missing.

- At least two Catalan officials defected from the ruling Junta pel Si party as Catalan President Carles Puigdemont cancelled a speech regarding snap elections and planned to draw back from declaring independence from Spain.

- Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte presented his 3rd cabinet, which took a record of 225 days of negotiations to form the government composed of VVD, D66, CDA and CU parties.

- The Trump Administration’s Department of Justice settled two lawsuits which alleged that the Obama Administration’s Internal Revenue Service targeted conservative groups.

- Nearly 3,000 files related to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 were released, while US President Donald Trump ordered others to be withheld citing national security concerns.

- Voters to Kenya went to the polls following the annulment of the results in the Kenyan general election – President Uhuru Kenyatta won with a 98% majority following an opposition boycott.

- Venezuela’s democratic opposition won the Sakharov Prize, the European Union’s top human rights award.

I search for simple pleasures for the simple man that I am.

I find myself in the London neighbourhood of Chelsea and I find it hard to imagine that until the 16th century Chelsea was nothing more than a tiny fishing village on the banks of the Thames centred around Chelsea Old Church.

It was royal advisor Thomas More (1478 – 1535) who started the upward trend by moving here in 1520, followed by members of the nobility, including King Henry VIII himself.

In the 18th century, Chelsea acquired its riverside houses along Cheyne Walk, which gradually attracted a posse of literary and intellectual types.

However, it was not until the late 19th century that the area began to earn its reputation as London’s very own Left Bank.

In the 1960s, Chelsea was at the forefront of “swinging London“, with the likes of David Bailey, Mick Jagger, George Best and the “Chelsea Set” hanging out in the boutiques and coffee bars.

Later, King’s Road became a catwalk for hippies and in the late 1970s it was the unlikely epicentre of the punk explosion.

Men wearing red trousers is about as countercultural as it gets in Chelsea nowadays, with franchise fashion rather than cutting edge couture the order of the day, though some of its residents like to think of themselves as a cut above the purely moneyed types of Kensington.

That said, King’s Road remains one of the better, more interesting shopping streets outside the West End and is well stocked with restaurants, while at its eastern end are two champions of contemporary and undiscovered art and theatre, the Saatchi Gallery and Royal Court Theatre respectively.

The area’s other aspects, oddly enough considering its reputation, is a military one, with the former Chelsea Barracks, the Royal Hospital and the National Army Museum.

And so, it is the litterati and artists, musicians and the military that grab the gaze of most London visitors.

Here in Chelsea the visitor can find:

- the Royal Court Theatre, a bastion of new theatre writing since John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger sent tremors through the Establishment in 1956.

- the Peter Jones department store, London’s finest glass curtain building

- Holy Trinity, the finest arts and crafts church in London.

- Saatchi Gallery, with changing exhibitions of contemporary art, much of it by largely unknown young artists, in 15 equally proportioned, whitewashed rooms.

- Number 30 Wellington Square, the fictional address of a comfortable ground floor flat of one “Bond, James Bond“.

- World’s End, once upon a time 1970s Let It Rock renamed SEX and then renamed again Seditionaries, with its landmark backwards running clock, continues to offer the eclectic to the eccentric.

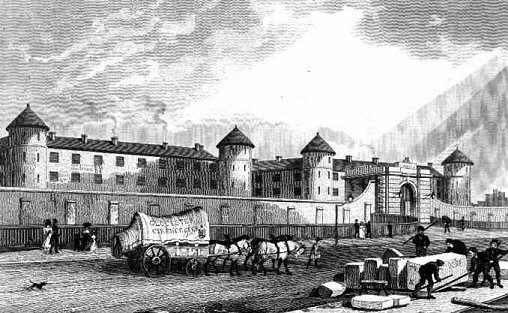

- Royal Hospital Chelsea is so odd that it fits perfectly within Chelsea, for here:

-

- Scarlet and navy blue army veterans (the Chelsea Pensioners) parade up and down King’s Road

-

-

- (And on 29 May – wearing tricorn hats and carrying a gilded statue of Charles I festooned with oak leaves – commemorate the day after the disastrous 1651 Battle of Worchester, when the future King hid in an oak tree to escape his pursuers)

-

(1 May 2020: Sadly, four Pensioners have died from the corona virus pandemic.)

-

- Here one finds a fresco in the hospital chapel of Jesus patriotically bearing the flag of St. George, the standard of England

-

- Here in the hospital’s Ranelagh Gardens (once called “London’s pleasure gardens“) is held the world’s finest horticultural event, the Chelsea Flower Show, with over 150,000 visitors over two days.

(1 May 2020: Both the Pensioners’ Parade and the Flower Show will not happen this year of the Pandemic.)

- Cheyne (pronounced “chainy“) Walk boasts the most blue plaques in a single street, for here lived:

-

- Novelist Henry James (#21)(1843 – 1916)

-

- Novelist Mary Ann Evans (better known by her penname “George Eliot“)(1819 – 1880)(#4)

-

- Poet / playwright Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900)(#1 and #34)

-

- Composer Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872 – 1958)(#13)

-

- Rolling Stone Mick Jagger (#48)

-

- Rolling Stone Keith Richards (#3)

-

- Painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834 – 1903)(#96)

-

- Engineer Marc Isambard Brunel (1769 – 1849) and his son, engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806 – 1859)(#99)

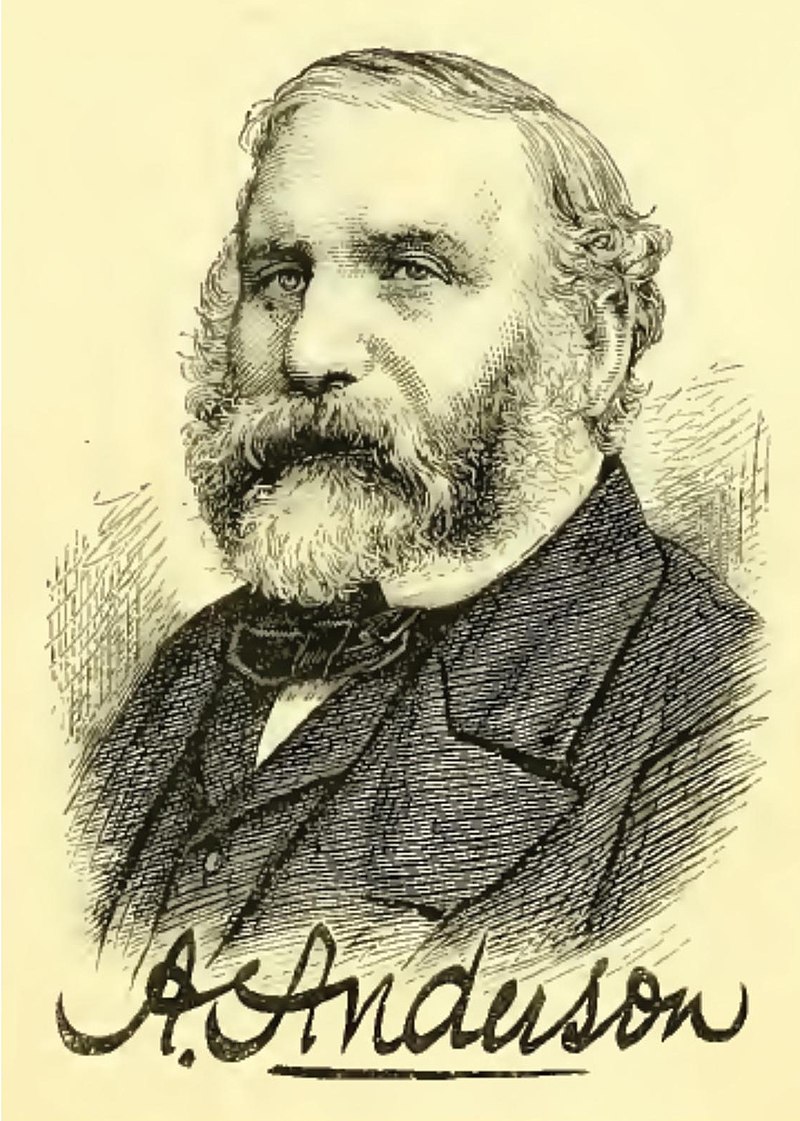

Above: Marc Isambard Brunel

Above: Isambard Kingdom Brunel

-

- Painter J.M.W. (Joseph Mallord William) Turner (1775 – 1851)(#119)

-

- Historian Thomas Carlyle (1795 – 1881)(#24)

(Caryle’s House is a museum today.)

- Chelsea Old Church, where one finds a garish gilded statue of Thomas More (“Scholar, Statesman, Saint“), Lady Cheyne’s memorial and More’s first wife’s (Jane Colt) memorial.

- Crosby Hall, once owned by More and once occupied by the future King Richard III (1452 – 1485)(and used as a setting by William Shakespeare) is now privately owned but visible from Cheyne Walk.

Above: King Richard III (1452 – 1485)

- Nearby Brompton Cemetery, close to the Chelsea Football Club, here one can find the graves of:

-

- Frederick Richards Leyland (1831 – 1892)(president of the National Telephone Company)(His final resting place resembles a bizarre copper green jewel box on stilts, smothered with swirling wrought ironwork)

-

- Suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst (1831 – 1892)

-

- Henry Cole (1808 – 1882)(the man behind the Great Exhibition and the V & A Museum / inventor of the first commercial Christmas card)

-

- Fanny Brawne (1800 – 1865)(the love of poet John Keats’ life)

-

- John Snow (1813 – 1858)(Queen Victoria’s anaesthetist)

-

- And the now empty gravesite of Long Wolf (1843 – 1923)(a Sioux Indian chief who died in London while on tour with Buffalo Bill Cody’s travelling Wild West Show)(The Chief’s body has since been returned to his descendants in America.).

- By Putney Bridge, Fulham Palace, once the largest moated site in all of England, (sadly the moat was filled in in 1921) was the residence of the Bishop of London from 704 to 1973 and features a museum containing a mummified rat, as well as a garden with a maze made of miniature box hedges.

I will say no more of these things, for I know no more of these things having not seen them myself.

What I have seen and thus the subject of this post was a botanical bounty near the banks of the Thames, the Chelsea Physic Garden.

Horticulturalists and herbalists will delight in this enchanting walled garden containing around 5,000 plant species from all over the world.

It is a rather small garden and a little too close to the Chelsea Embankment to be a peaceful oasis, but it is enjoyable nonetheless even for those uninterested in botany.

Plants are everywhere.

They live in almost every surface on Earth, from the highest mountains to the lowest valleys, from the coldest and driest environments to some of the hottest and wettest places on our planet.

Nobody knows for certain how many species of plants there actually are.

So far, scientists have counted about 425,000, but more are being discovered every day.

There are clear patterns as to where on Earth plants thrive best and the conditions they need.

Understanding these patterns is crucial to preserving all forms of life on Earth, including us.

Because without plants there would be no humans.

Plants create and regulate the air we breathe.

They provide us with food, medicines, textiles to make our clothes and materials to build our homes.

So how did the Earth reach the diversity and variety of plant life we see today?

What did the first plants look like?

What are the biggest, smallest, weirdiest and smelliest plants on the planet?

Wander through the Chelsea Physic Garden and all will be revealed!

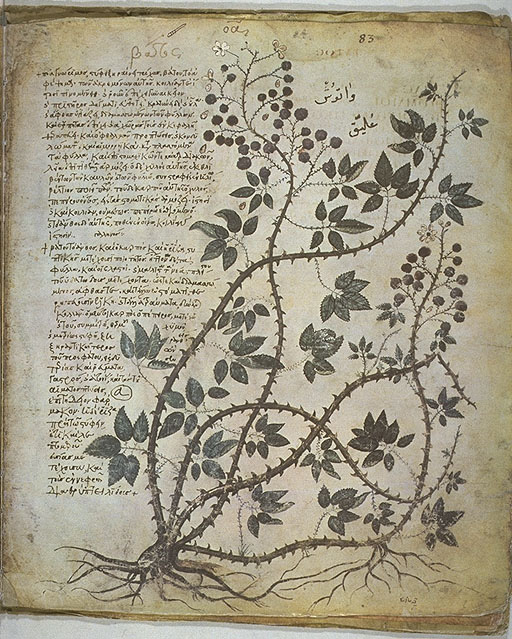

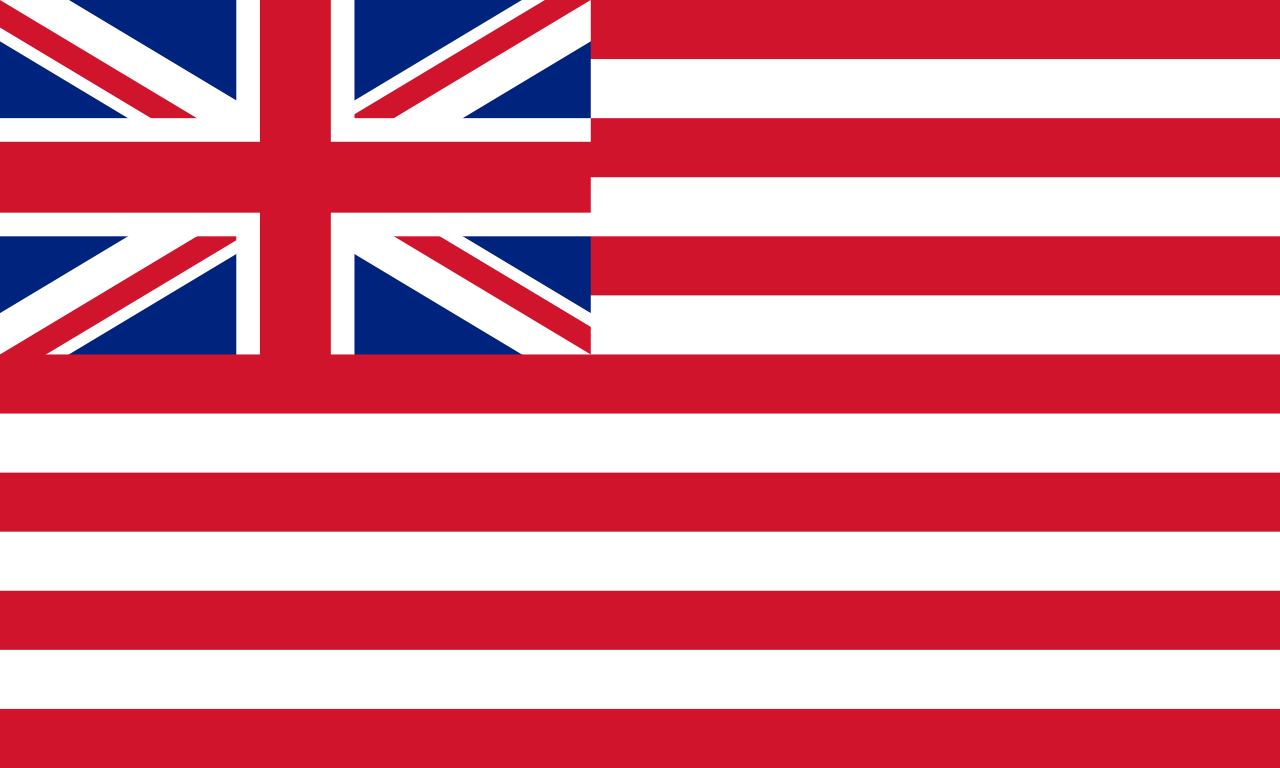

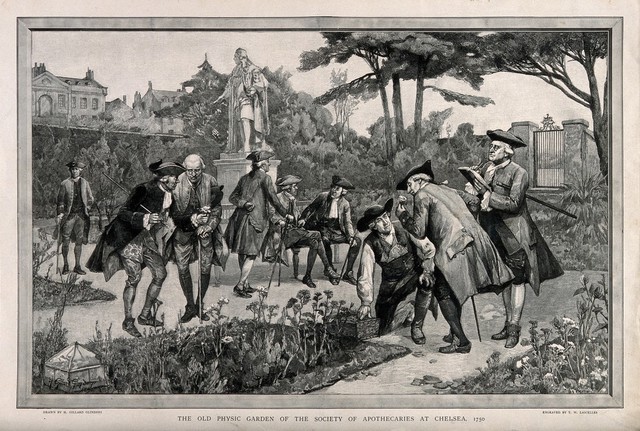

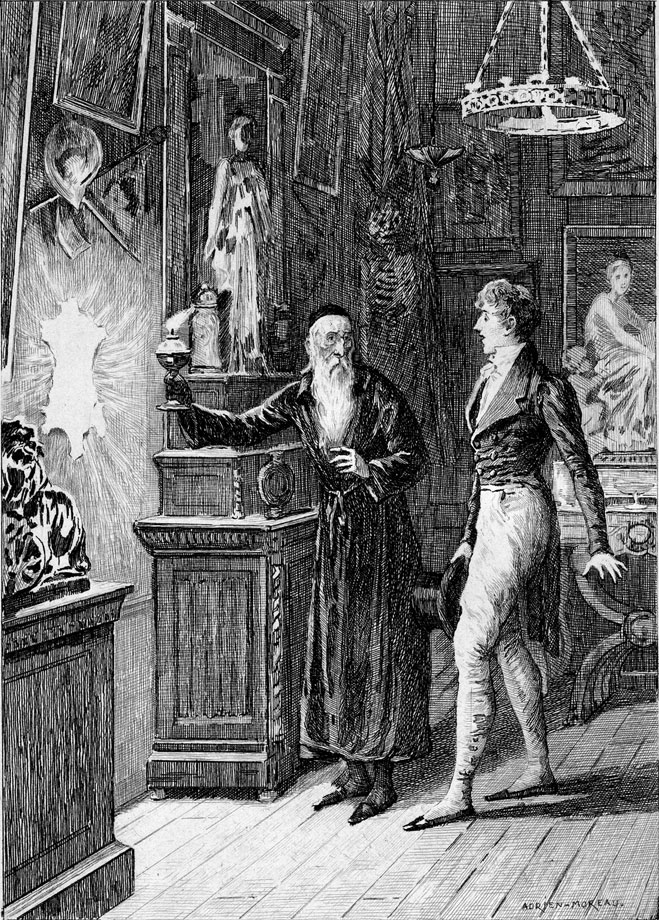

The Garden’s collection was founded in 1673 by the Society of Apothecaries to study the medicinal properties of plants and was jealously guarded until 1983 it became a registered charity and was opened to the general public for the first time.

It is the oldest botanical garden in the country after Oxford’s and Edinburgh’s.

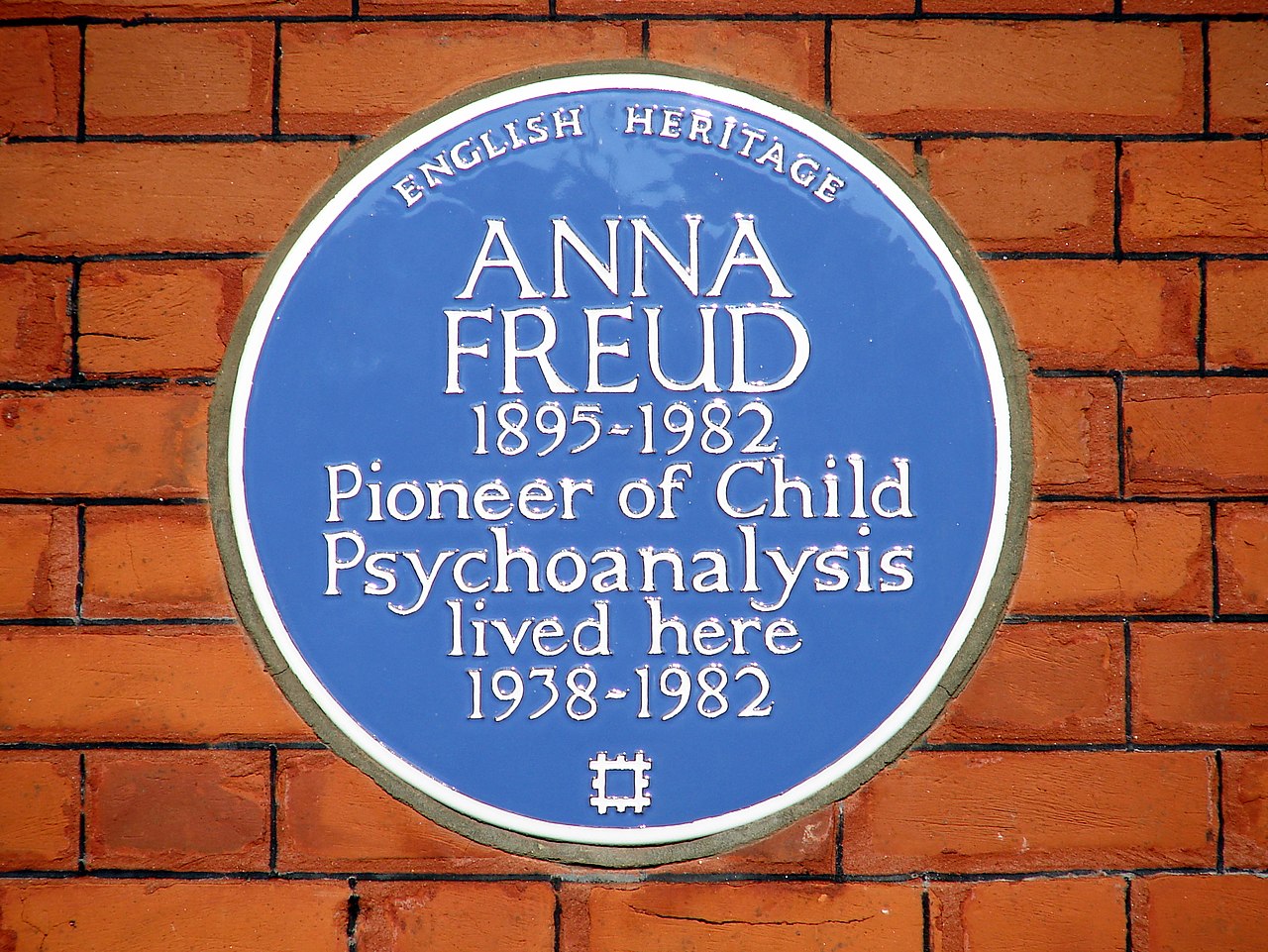

The Garden is a member of the London Museums of Health and Medicine and is listed in the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England by English Heritage.

The first cedars grown in England were planted here in 1683.

Cotton seed was sent from here to the American colonies in 1732.

England’s first rock garden was constructed here in 1773.

Britain’s oldest and largest olive tree is here, protected by the Garden’s heat-trapping high brick walls, along with what is probably the world’s northernmost grapefruit growing outdoors.

This extraordinary place has had a wide-reaching impact around the world, becoming at its peak, during the 1700s, the most important centre for plant exchange on the planet.

The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries initially founded the Garden on a leased site of Sir John Danvers’ well-established garden in Chelsea, London.

This house, called Danvers House, adjoined the Mansion that had once been the house of Sir Thomas More.

Danvers House was pulled down in 1696 to make room for Danvers Street.

The site was chosen for its proximity to the river, which at the time was the most important transport route in London and allowed the Apothecaries to moor their barge and carry out botanising expeditions to surrounding areas.

The site also offered a south-facing aspect and well-managed soil, having been within an area of market gardens.

The Apothecaries appointed John Watts as their first Curator in 1680 and charged him with growing and maintaining the recognized medicinal herbs of the day.

During Watts’ stewardship the first greenhouse appeared in the Garden, which was heated with an external stove and glazed on one side.

As the first greenhouse of this kind in England, it allowed the Garden to grow hitherto unknown rare tropical and tender species.

That same year a young apprentice from Ireland named Hans Sloane began his studies at the Garden.

Little did the Apothecaries know that Sloane would one day become responsible for ensuring the Garden’s survival to this day.

Above: Hans Sloane (1660 – 1753)

After qualifying in 1687 Sloane travelled to Jamaica to serve as private physician to the second Duke of Albemarle.

Two years later, Sloane returned to London armed with a special recipe and bottles of a compound, sourced from plants, which would go on to make him a fortune.

The recipe was for milk chocolate – a drink he had seen Jamaican mothers give to children with colic – and the compound, sourced from the tropical tree Cinchona pubescens, quinine – a medicine capable of preventing and curing malaria.

Sloane quickly established himself back in London, making considerable sums from his chocolate recipe (cocoa with milk) and sales of quinine.

Mary Somerset, Duchess of Beaufort (1630 – 1715) (also known by her other married name of Mary Seymour, Lady Beauchamp and her maiden name Mary Capell) was an English noblewoman, gardener and botanist.

On 28 June 1648, Mary married her first husband Henry Seymour, Lord Beauchamp, and they had one son and one daughter.

Her husband was a Royalist, imprisoned during the English Civil War.

Her second husband, whom she married on 17 August 1657 was Henry Somerset (1629 – 1700), who became 1st Duke of Beaufort, by whom she had six children.

During the Popish Plot, she was required in her husband’s absence to call out the militia, to deal with a false alarm of a French invasion at the Isle of Purbeck, and did so “in a state of deadly fear“.

(The Popish Plot was a conspiracy invented by Titus Oates that between 1678 and 1681 gripped the Kingdoms of England and Scotland in anti-Catholic hysteria.

Above. Titus Oates (1649 – 1705)

Oates alleged that there was an extensive Catholic conspiracy to assassinate King Charles II, accusations that led to the executions of at least 22 men and precipitated the Exclusion Bill (which sought to exclude the King’s brother and heir presumptive, James, Duke of York, from the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland because he was Roman Catholic) Crisis.

Eventually Oates’s intricate web of accusations fell apart, leading to his arrest and conviction for perjury.)

Above: King Charles II (1630 – 1685)

The supposed invasion, like much that happened (or failed to happen) during the Plot, was simply the result of public hysteria.

Despite this moment of panic, in general she maintained a detached and rational attitude to the Plot, expressing her amazement that the informer William Bedloe (1650 – 1680), whom she knew to be “a villain whose word would not have been taken at sixpence“, should now have “power to ruin any man“.

She attended the trial of the Catholic barrister Richard Langhorne, presumably in case Bedloe, a bitter enemy of her husband, made any charges against him, and took notes of the evidence.

Above: Richard Langhorne (1624 – 1679)

When Bedloe protested at her presence, the Lord Chief Justice, William Scroggs, pointed out that the trial was open to the public, and asked irritably what a woman’s notes amounted to anyway:

“No more than her tongue, truly“.

Above: William Scroggs (1623 – 1683)

Mary was a notoriously exacting employer “striking terror in the hearts of her servants“:

Every day she would do a tour of the house and grounds (Beaufort House), and any servant not found hard at work was instantly dismissed.

Even neighbouring landowners held her in awe, and were anxious not to cross her.

Above: Beaufort House, Chelsea, today

The Duchess of Beaufort was one of Britain’s earliest distinguished lady gardeners.

She began seriously to collect plants in the 1690s and her interest in gardening intensified in her widowhood.

She had the assistance of such well-known gardeners and botanists as George London (1640 – 1714) and Leonard Plukenet (1641 – 1706).

Seeds came to her from the West Indies, South Africa, India, Sri Lanka, China and Japan.

In 1702, she engaged the services of William Sherard (1659 – 1728) as tutor for her grandson, “he loving my diversion so well“.

Sherard helped introduce more than 1,500 plants, most of them greenhouse subjects, to her collection, at Badminton House or at Beaufort House, Chelsea.

Sir Robert Southwell, Sir Hans Sloane and Jacob Bobart are all known to have sought her assistance in growing and identifying plants from unidentified seeds, some of which had come to them through the Royal Society of London.

In 1712, Dr. Hans Sloane, as wealthy physician, purchased the entire Manor of Chelsea.

Mary’s London house was next to that of Sir Hans Sloane, making her a neighbour of the Chelsea Physic Garden.

Her herbarium, in twelve volumes, ‘gathered and dried by order of Mary Duchess of Beaufort‘, she bequeathed to Sir Hans Sloane, by whose bequest it came to the Natural History Museum.

Her two-volume set of drawings of her most choice exotics remains in the library at Badminton.

Among her introductions to British gardening, most of which were greenhouse plants, are Pelargonium zonale one of the parents of the zonal pelargoniums of gardens, ageratum and the Blue Passion Flower (Passiflora caerulea).

She is also notable for being one of the earliest women known to have her own collection of the Philosophical Transactions, the journal of the Royal Society of London.

In 1722, Sloane leased four acres (1.6 hectares) of land to the Apothecaries for five pounds a year in perpetuity – a bargain even back then.

The deed of covenant is on display, stating the Garden’s purpose, that “apprentices and others may the better distinguish good and useful plants from those that bear resemblance to them and yet are hurtful“.

He also required the Apothecaries to provide 50 pressed plant specimens a year to the Royal Society until 2,000 had been received.

This process continued for many years under the direction of Head Gardeners or Curators and quickly exceeded the numbers required by Sloane.

A statue of Sloane stands at the centre of the garden.

Notable among the annual consignments were those sent in 1724, which contained 50 species from the Geraniaceae family (geraniums) – the first record of the Garden’s long association with these plants.

James Sherard (1666 – 1738) was an English apothecary, botanist and amateur musician.

On 7 February 1682, apothecary Charles Watts, who served as curator of Chelsea Physic Garden, took him in as an apprentice.

After honing his craft with Watts, Sherard moved to Mark Lane, London, where he started his own very successful business.

In time, Sherard came into contact with Wriothesley Russell, 2nd Duke of Bedford through his brother, who had once served as a tutor in Russell’s family.

Sherard dedicated his first set of trio sonatas to Russell.

One surviving copy of the work was owned by an apothecary named William Salter.

He wrote commentary in the margins, including a note that Sherard was friends with George Frideric Handel (1685 – 1759).

Sherard published a second set of trio sonatas in 1711.

Sherard’s extensive collection of manuscripts of vocal and instrumental music is preserved in the Bodleian Library (Oxford) and includes unique copies of German church music among other items.

In 1711, around the time Sherard finished composing his second set of sonatas, the Duke died, and Sherard’s interest in music seems to have died with him.

He also fell ill with gout, which prevented him from playing the violin.

Instead, he turned to botany.

He wrote in August 1716 that “of late the love of botany has so far prevailed as to divert my mind from things I formerly thought more material“.

Upon retiring from his business in Mark Lane in the 1720s, he had already acquired an ample fortune.

He purchased two manors in Leicestershire and a property at Eltham in Kent, near London, where he largely resided.

Sherard soon found himself maintaining a growing collection of rare plants at Eltham.

Above: Eltham Palace

Despite his ill health, he made several trips to continental Europe in search of seeds for his garden, which soon became recognized as one of the finest in England.

In 1721, in order to help with a projected revision of Caspar Bauhin’s Pinax of 1623, William Sherard brought the German botanist Johann Jacob Dillenius (1684 – 1747) to England.

In 1732, James published Dillenius’ illustrated catalog of the collection at Eltham.

According to Blanche Henrey, it was “the most important book to be published in England during the 18th century on plants growing in a private garden” and a major work for the pre-Linnaean taxonomy of South African plants, notably the succulents of the Cape Province.

Dillenius’ herbarium specimens from Eltham are preserved in the herbarium of the Oxford Botanical Garden.

Above: Johann Jacob Dillenius

Samuel Doody (1656–1706) was an early English botanist.

The eldest of the second family of his father, John Doody, an apothecary in Staffordshire who later moved to London where he had a shop in The Strand, Samuel was born in Staffordshire.

He went into his father’s business, to which he succeeded in 1696.

He undertook the care of the Apothecaries’ Garden at Chelsea in 1693, at a salary of £100, which he continued until his death.

His sole contribution as an author seems to be a paper in the Philosophical Transactions (1697), on a case of dropsy (fluid retention / swelling) in the breast.

Doody had given some attention to botany before 1687, the date of a commonplace book, but his help is first acknowledged by John Ray in 1688 in the second volume of the Historia Plantarum.

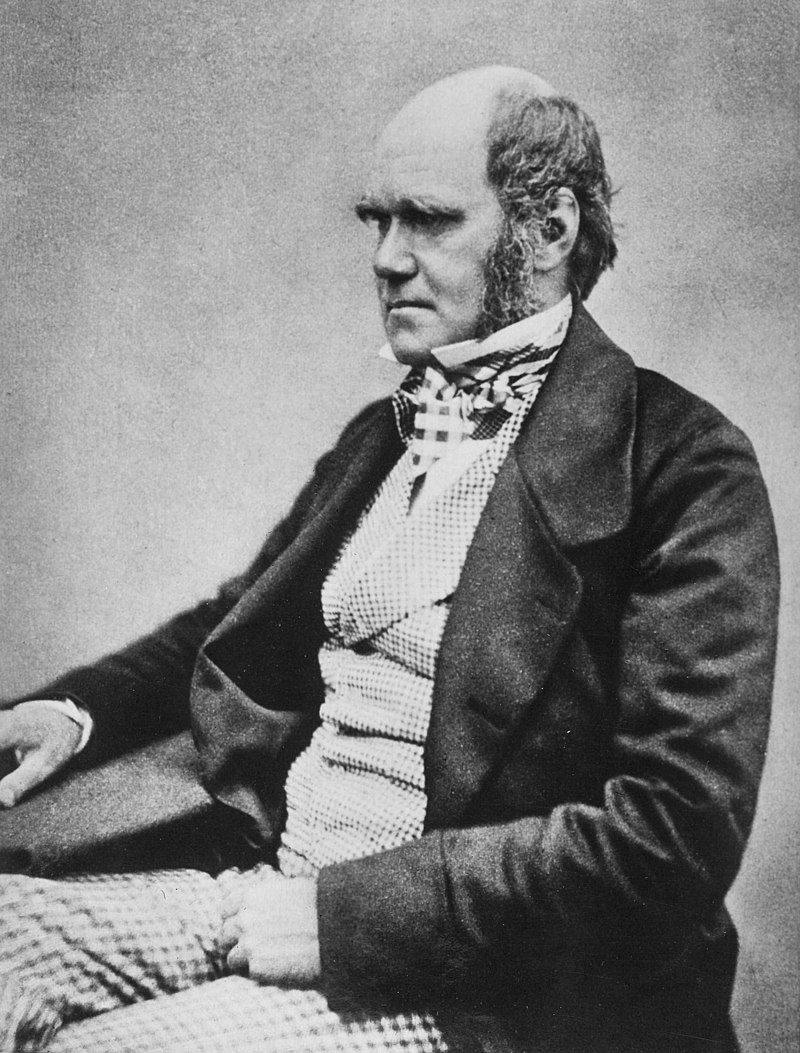

(John Ray (1627 – 1705) was an English naturalist widely regarded as one of the earliest of the English parson-naturalists.

He published important works on botany, zoology and natural theology.

His classification of plants in his Historia Plantarum, was an important step towards modern taxonomy.

Ray rejected the system of dichotomous division by which species were classified according to a pre-conceived, either/or type system, and instead classified plants according to similarities and differences that emerged from observation.

He was among the first to attempt a biological definition for the concept of species.)

Above: John Ray

Doody was intimate with the botanists of his time: Ray, Leonard Plukenet, James Petiver (1665 – 1718) and Hans Sloane.

Doody devoted himself to cryptogams – (A cryptogam – scientific name Cryptogamae – is a plant (in the wide sense of the word) that reproduces by spores, without flowers or seeds. “Cryptogamae” (Greek: “hidden” + “to marry”) means “hidden reproduction“, referring to the fact that no seed is produced, thus cryptogams represent the non-seed bearing plants.) – at that time very little studied, and became an authority on them.

The results of his herborisations round London were recorded in his copy of Ray’s ‘Synopsis,’ now in the British Museum.

Above: A cryptogam fern (Polystichum setiferum)

Mark Catesby (1683 – 1749) was an English naturalist.

Between 1729 and 1747 Catesby published his Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, the first published account of the flora and fauna of North America.

It included 220 plates of birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, insects, mammals and plants.

An acquaintance with the naturalist John Ray led to Catesby becoming interested in natural history.

The death of his father left Catesby enough to live on, so in 1712, he accompanied his sister Elizabeth to Williamsburg, Virginia.

She was the wife of Dr. William Cocke, who had been a member of the Council and Secretary of State for the Colony of Virginia.

According to their father’s will, Elizabeth had married Dr. Cocke against her father’s wishes.

Catesby visited the West Indies in 1714, and returned to Virginia, then home to England in 1719.

Catesby had collected seeds and botanical specimens in Virginia and Jamaica.

He sent the pressed specimens to Dr Samuel Dale of Braintree in Essex, and gave seeds to a Hoxton nurseryman Thomas Fairchild as well as to Dale and to the Bishop of London, Dr Henry Compton.

Plants from Virginia, raised from Catesby’s seeds, made his name known to gardeners and scientists in England, and in 1722 he was recommended by William Sherard to undertake a plant-collecting expedition to Carolina on behalf of certain members of the Royal Society.

From May 1722, Catesby was based in Charleston, South Carolina, and travelled to other parts of that colony, collecting plants and animals.

He sent preserved specimens to Hans Sloane and to William Sherard, and seeds to various contacts including Sherard and Peter Collinson.

(Peter Collinson (1694 – 1768) was a Fellow of the Royal Society, an avid gardener and the middleman for an international exchange of scientific ideas in mid-18th century London.

He is best known for his horticultural friendship with John Bartram and his correspondence with Benjamin Franklin about electricity.)

Consequently, Catesby was responsible for introducing such plants as Catalpa bignonioides and the eponymous Catesbaea spinosa (lilythorn) to cultivation in Europe.

Catesby returned to England in 1726.

Catesby spent the next twenty years preparing and publishing his Natural History.

Publication was financed by subscriptions from his “Encouragers” as well as an interest-free loan from one of the fellows of the Royal Society, the Quaker Peter Collinson.

Catesby learnt how to etch the copper plates himself.

The first eight plates had no backgrounds, but from then on Catesby included plants with his animals.

Catesby’s original preparatory drawings for Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands are in the Royal Library, Windsor Castle, and selections have been exhibited in the US, Japan and various places in England.

On 5 March 1747, Catesby read a paper entitled “Of birds of passage” to the Royal Society in London and he is now recognised as one of the first people to describe bird migration.

Philip Miller was appointed Head Gardener at Sloane’s suggestion in 1722 and served the Garden for nearly 50 years.

During his long tenure Miller firmly established the Garden as the world’s leading centre for botanical plant exchange.

This seed-exchange programme was established following a visit in 1682 from Dutch botanist Paul Hermann (1646 – 1695) of the Hortus Botanicus Leiden and still continues.

The seed exchange program’s most notable act may have been the introduction of cotton into the colony of Georgia and more recently, the worldwide spread of the Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus).

Johann Amman (or Johannes Amman or Иоганн Амман) (1707 in Schaffhausen – 1741 in St Petersburg), was a Swiss-Russian botanist, a member of the Royal Society and professor of botany at the Russian Academy of Sciences at St Petersburg.

He is best known for his Stirpium Rariorum in Imperio Rutheno Sponte Provenientium Icones et Descriptiones published in 1739 with descriptions of some 285 plants from Eastern Europe and Ruthenia (now Ukraine).

The plates are unsigned, though an engraving on the dedicatory leaf of the work is signed “Philipp Georg Mattarnovy“, a Swiss-Italian engraver, Filippo Giorgio Mattarnovi (1716-1742), who worked at the St. Petersburg Academy.

Amman was a student of Herman Boerhaave at Leyden from where he graduated as a physician in 1729.

(Herman Boerhaave (1668 – 1738) was a Dutch botanist, chemist, Christian humanist, and physician of European fame.

He is regarded as the founder of clinical teaching and of the modern academic hospital and is sometimes referred to as “the father of physiology“.

Boerhaave introduced the quantitative approach into medicine and is best known for demonstrating the relation of symptoms to lesions.

He was the first to isolate the chemical urea from urine.

He was the first physician to put thermometer measurements to clinical practice.

His motto was Simplex sigillum veri:

‘Simplicity is the sign of the truth’.

He is often hailed as the “Dutch Hippocrates“.)

Amman came from Schaffhausen in Switzerland in 1729 to help Hans Sloane curate his natural history collection.

Sloane was founder of the Chelsea Physic Garden and originator of the British Museum.

Amman went on to St Petersburg at the invitation of Johann Georg Gmelin (1709-1755) and became a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, regularly sending interesting plants, such as Gypsophila paniculata (baby’s breath), back to Sloane.

Above: Gypsophila paniculata (baby’s breath)

Carl Linnaeus maintained a lively correspondence with Amman between 1736 and 1740.

(Carl Linnaeus or Carl von Linné (1707 – 1778) was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming organisms.

He is known as the “father of modern taxonomy“.

He received most of his higher education at Uppsala University and began giving lectures in botany there in 1730.

He lived abroad between 1735 and 1738, where he studied and also published the first edition of his Systema Naturae in the Netherlands.

He then returned to Sweden where he became professor of medicine and botany at Uppsala.

In the 1740s, he was sent on several journeys through Sweden to find and classify plants and animals.

In the 1750s and 1760s, he continued to collect and classify animals, plants, and minerals, while publishing several volumes.

He was one of the most acclaimed scientists in Europe at the time of his death.

Philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau sent him the message:

“Tell him I know no greater man on Earth.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote:

“With the exception of Shakespeare and Spinoza, I know no one among the no longer living who has influenced me more strongly.”

Swedish author August Strindberg wrote:

“Linnaeus was in reality a poet who happened to become a naturalist.”

Linnaeus has been called Princeps botanicorum (Prince of Botanists) and “The Pliny of the North“.

He is also considered as one of the founders of modern ecology.

In botany and zoology, the abbreviation L. is used to indicate Linnaeus as the authority for a species’ name.

Linnaeus’s remains comprise the type specimen for the species Homo sapiens following the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, since the sole specimen that he is known to have examined was himself.)

William Houstoun (occasionally spelt Houston) (1695 – 1733) was a Scottish surgeon and botanist who collected plants in the West Indies, Mexico and South America.

Houstoun was born in Houston, Renfrewshire.

He began a degree course in medicine at St Andrew’s University, but interrupted his studies to visit the West Indies, returning in 1727.

On 6 October 1727, he entered the University of Leyden to continue his studies under Boerhaave, graduating M.D. in 1729.

It was during his time at Leyden that Houstoun became interested in the medicinal properties of plants.

After returning to England that year, he soon sailed for the Caribbean and the Americas employed as a ship’s surgeon for the South Sea Company.

He collected plants in Jamaica, Cuba, Venezuela and Veracruz, despatching seeds and plants to Philip Miller, head gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden in London.

Notable among these plants was Dorstenia contrayerva, a reputed cure for snakebite, and Buddleja americana, the latter named by Linnaeus, at Houstoun’s request, for the English cleric and botanist Adam Buddle, although Buddle could have known nothing of the plant as he had died in 1715.

Above: Dorstenia contrajerva (Theodor Dorsten’s anti-snakebite plant)

Above: Buddleja americana (American Butterfly bush)

Houstoun published accounts of his studies in Catalogus plantarum horti regii Parisiensis.

When Houstoun returned to London in 1731, he was introduced to Sir Hans Sloane by Miller.

Sloane commissioned him to undertake a three-year expedition, financed by the trustees for the Province of Georgia ‘for improving botany and agriculture in Georgia‘, and to help stock the Trustee’s Garden planned for Savannah.

Houstoun initially sailed to the Madeira Islands to gather grape plantings before continuing his voyage across the Atlantic.

However he never completed his mission as he ‘died from the heat‘ on 14 August 1733 soon after arriving in Jamaica.

He was buried at Kingston.

Above: Modern Kingston, Jamaica

Isaac Rand, a member and a fellow of the Royal Society published a condensed catalogue of the Garden in 1730, Index plantarum officinalium, quas ad materiae medicae scientiam promovendam, in horto Chelseiano.

Isaac Rand (1674–1743) was an English botanist and apothecary, who was a lecturer and director at the Chelsea Physic Garden.

Isaac was the son of James Rand, who in 1674 agreed, with thirteen other members of the Society of Apothecaries, to build a wall round the Chelsea Botanical Garden.

Isaac Rand was already an apothecary practising in the Haymarket, London, in 1700.

In Leonard Plukenet’s Mantissa, published in that year, Rand is mentioned as the discoverer, in Tothill Fields, Westminster, of the plant now known as Rumex palustris, and was described as “stirpium indagator diligentissimus … pharmacopœus Londinensis, et magnæ spei botanicus.’

Above: Rumex palustrus (Marsh dock)

He seems to have paid particular attention to inconspicuous plants, especially in the neighbourhood of London.

Thus Samuel Doody records in a manuscript note:

“Mr. Rand first showed me this beautiful dock Rumex maritimus, growing plentifully in a moist place near Burlington House.”

Adam Buddle, in his manuscript Flora, which was completed before 1708, attributes to him the finding of Mentha pubescens “about some ponds near Marybone” and of the plant styled by James Petiver “Rand’s Oak Blite” (Chenopodium glaucum).

Above: Mentha pubescens (hairy mint)

Above: Chenopodium glaucum (oak-leaved goosefoot)

In 1707 Rand, and nineteen other members, including Petiver and Joseph Miller, took a lease of the Chelsea Garden, to assist the Society of Apothecaries, and were constituted trustees.

For some time prior to the death of Petiver in 1718, Rand seems either to have assisted him or to have succeeded him in the office of demonstrator of plants to the Society.

In 1724, Rand was appointed to the newly created office of præfectus horti, or director of the Garden.

Among other duties, Rand had to give at least two demonstrations in the garden in each of the six summer months, and to transmit to the Royal Society the fifty specimens per annum required by the terms of Sir Hans Sloane’s donation of the Garden.

Lists of the plants he sent for several years are in the Sloane Manuscripts.

Philip Miller was gardener throughout Rand’s tenure of the office of præfectus and it was in 1736 that Carl Linnæus visited the Garden.

Dillenius’s edition of John Ray’s Synopsis Methodica Stirpium Britannicarum (1724) contains several records by Rand, whose assistance is acknowledged in the preface.

Rand is specially mentioned by the illustrator Elizabeth Blackwell as having assisted her with specimens for her Curious Herbal (1737–39), which was executed at Chelsea.

Rand is one of those who prefix to the work a certificate of accuracy and a copy in the British Museum Library has manuscript notes by him.

Rand prompted botanical artists like Blackwell and Georg Dionysius Ehret, to make illustrations of the living herbaceous plants produced by the Garden.

(Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708 – 1770) was born in Germany to Ferdinand Christian Ehret, a gardener and competent draughtsman, and Anna Maria Ehret.

Beginning his working life as a gardener’s apprentice near Heidelberg, he became one of the most influential European botanical artists of all time.

His first illustrations were in collaboration with Carl Linnaeus and George Clifford in 1735-1736.

Clifford, a wealthy Dutch banker and governor of the Dutch East India Company was a keen botanist with a large herbarium.

He had the income to attract the talents of botanists such as Linnaeus and artists like Ehret.

Together at the Clifford estate, Hartecamp, which is located south of Haarlem in Heemstede near Bennebroek, they produced Hortus Cliffortianus in 1738, a masterpiece of early botanical literature.)

Rand was friends with Mark Catesby, receiving seeds he collected in the Americas and a subscriber to his seminal Natural History of the region.

Rand produced two catalogues of the Garden and coöperated with the Leiden Physic Garden via Herman Boerhaave.

In 1730, perhaps somewhat piqued by Philip Miller’s issue of his Catalogus in that year, Rand printed the aforementioned Index plantarum officinalium in horto Chelseiano.

In a letter to Samuel Brewer, dated ‘Haymarket, 11 July 1730‘, Rand says that the Apothecaries’ Company had ordered the Index to be printed.

In 1739 Rand published ‘Horti medici Chelseiani Index Compendiarius,’ an alphabetical Latin list occupying 214 pages.

Rand’s widow presented his botanical books and an extensive collection of dried specimens to the company, and bequeathed 50s a year to the præfectus horti for annually replacing twenty decayed specimens in the latter by new ones.

This herbarium was preserved at Chelsea, with those of Ray and Dale, until 1863, when all three were presented to the British Museum.

Linnæus retained the name Randia, applied by William Houston in Rand’s honour to a genus of tropical Rubiaceæ.

Above: Randia (Indigo berry)

Jacob van Huysum (1688 – 1740) was an 18th-century botanical painter from the northern Netherlands.

Both his father Justus van Huysum (1659–1716) and his brother Jan van Huysum (1682–1749) were celebrated flower painters.

His manner of painting was very like that of his brother.

His approach to botanical illustration, while preserving botanical accuracy, captured a more artistic aspect of his subject.

This contrasts with the meticulously exact mode of Georg Dionysius Ehret, his contemporary colleague.

He produced most of the 50 illustrations for John Martyn’s Historia Plantarum Rariorum (London: 1728-38), and all the drawings for Catalogus Plantarum, an index of trees, shrubs, plants and flowers (London: 1730).

Historia Plantarum Rariorum depicted plants from the Chelsea Physic Garden and the Cambridge Botanic Garden.

These plants had come from the Cape of Good Hope, North America, the West Indies and Mexico.

Each plate was dedicated to a patron and showed an engraved coat-of-arms or monogram.

The work was published in five parts of ten plates each between 1728 and 1737, and was sold by subscription.

The venture was not a financial success and publication ceased in 1737.

Above: Solidago virga-aurea (European goldenrod)

Meanwhile, so extensive was Miller’s impact on gardening that between 1731 and 1768 he doubled the number of plants cultivated in Britain.

In 1731 Miller published his Gardeners Dictionary, the most complete work on gardening of its time.

James Lee (1715 – 1795) was a Scottish gardener who had apprenticed at the Chelsea Physic Garden.

James Lee was a correspondent with Carl Linnaeus, through Lee’s connection with the Chelsea Physic Garden.

He compiled an introduction to the Linnaean system, An Introduction to Botany, published in 1760, which passed through five editions.

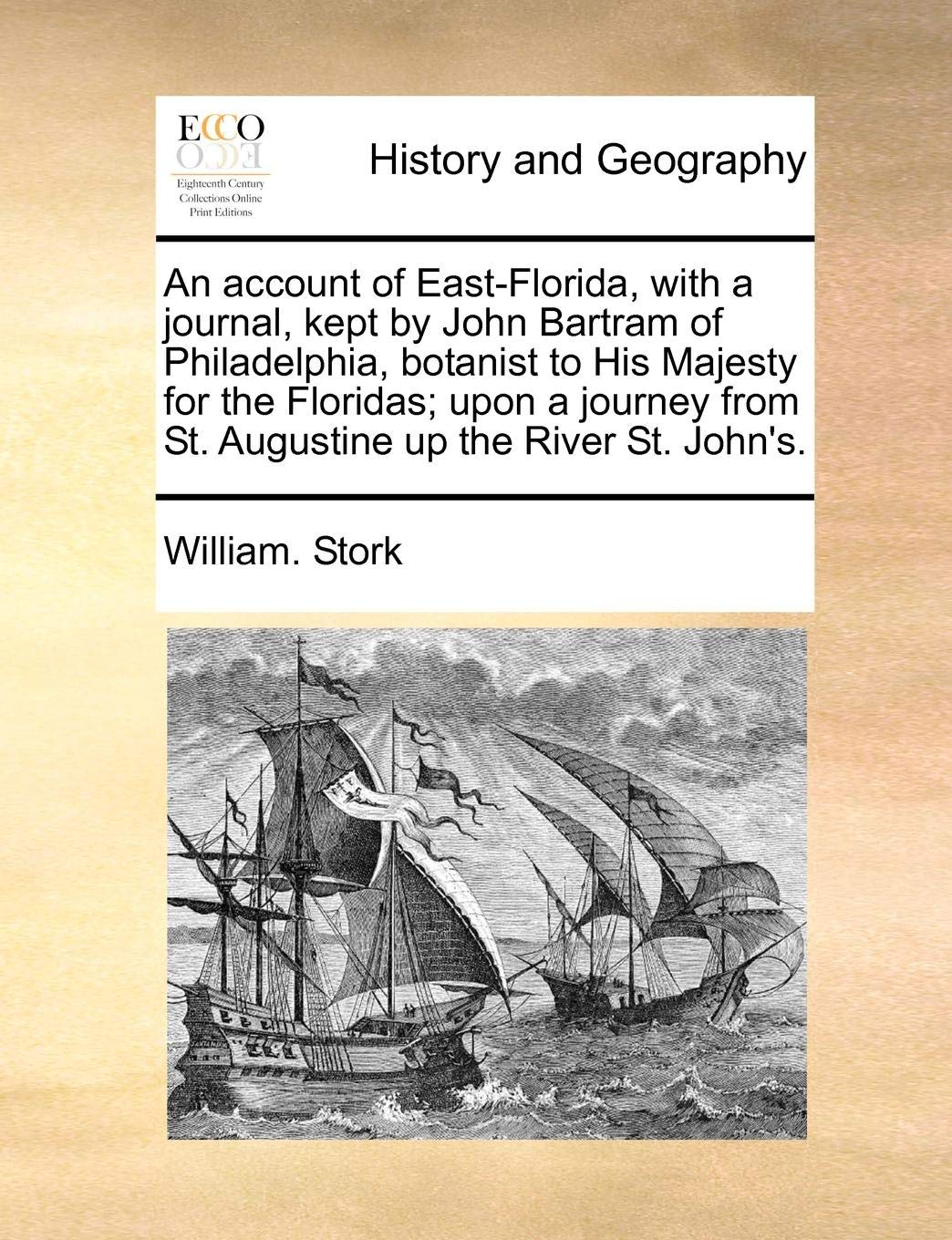

John Bartram (1699 – 1777) was an early American botanist, horticulturist and explorer.

Carl Linnaeus said he was the “greatest natural botanist in the world.”

Bartram was born into a Quaker farm family in colonial Pennsylvania.

He considered himself a plain farmer, with no formal education beyond the local school.

He had a lifelong interest in medicine and medicinal plants, and read widely.

His botanical career started with a small area of his farm devoted to growing plants he found interesting.

Later he made contact with European botanists and gardeners interested in North American plants and developed his hobby into a thriving business.

Bartram came to travel extensively in the eastern American colonies collecting plants.

In 1743 he visited the shores of Lake Ontario in the north and wrote Observations on the Inhabitants, Climate, Soil, Rivers, Productions, Animals, and other Matters Worthy of Notice, made by Mr. John Bartram in his Travels from Pennsylvania to Onondaga, Oswego, and the Lake Ontario, in Canada.

During the winter of 1765 – 1766 he visited East Florida in the south and an account of this trip was published with his journal.

He also visited the Ohio River in the west.

Many of his acquisitions were transported to collectors in Europe.

In return, they supplied him with books and apparatus.

Bartram, sometimes called the “father of American botany“, was one of the first practicing Linnaean botanists in North America.

His plant specimens were forwarded to Linnaeus, Dillenius and Gronovius, and he assisted Linnaeus’ student Pehr Kalm during his extended collecting trip to North America from 1748 to 1750.

(Laurens Theodoor Gronovius (1730 – 1777), also known as Laurentius Theodorus Gronovius or Laurens Theodoor Gronow, was a Dutch naturalist born in Leiden.

Throughout his lifetime Gronovius amassed an extensive collection of zoological and botanical specimens.

He is especially remembered for his work in the field of ichthyology, where he played a significant role in the classification of fishes.

In 1754 he published the treatise Museum ichthyologicum, in which he described over 200 species of fish.

He is also credited with developing a technique for preservation of fish skins.

Today, a number of these preserved specimens are kept in the Natural History Museum in London.)

Bartram was aided in his collecting efforts by colonists.

In Bartram’s Diary of a Journey through the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida, a trip taken from 1 July 1765 to 10 April 1766, Bartram wrote of specimens he had collected.

In the colony of British East Florida he was helped by Dr. David Yeats, secretary of the colony.

His 8-acre (32,000 m2) botanic garden, Bartram’s Garden in Kingsessing on the west bank of the Schuylkill, about 3 miles (5 km) from the center of Philadelphia is frequently cited as the first true botanic collection in North America.

He was one of the co-founders, with Benjamin Franklin, of the American Philosophical Society in 1743.

Bartram was particularly instrumental in sending seeds from the New World to European gardeners:

Many North American trees and flowers were first introduced into cultivation in Europe by this route.

Beginning in 1733, Bartram’s work was assisted by his association with the English merchant Peter Collinson.

Collinson, himself a lover of plants, was a fellow Quaker and a member of the Royal Society, with a familiar relationship with its president, Sir Hans Sloane.

Collinson shared Bartram’s new plants with friends and fellow gardeners.

Early Bartram collections went to Lord Petre, Philip Miller at the Chelsea Physic Garden, Mark Catesby, the Duke of Richmond, and the Duke of Norfolk.

In the 1730s, Robert James Petre, 8th Baron Petre of Thorndon Hall, Essex, was the foremost collector of North American trees and shrubs in Europe.

Earl Petre’s untimely death in 1743 led to his American tree collection being auctioned off to Woburn, Goodwood and other large English country estates.

Thereafter Collinson became Bartram’s chief London agent.

Bartram’s Boxes, as they then became known, were regularly sent to Peter Collinson every fall for distribution in England to a wide list of clients, including the Duke of Argyll, James Gordon, James Lee and John Busch, progenitor of the exotic Loddiges nursery in London.

The boxes generally contained 100 or more varieties of seeds, and sometimes included dried plant specimens and natural history curiosities as well.

Live plants were more difficult and expensive to send and were reserved for Collinson and a few special correspondents.

In 1765 after lobbying by Collinson and Benjamin Franklin in London, King George III rewarded Bartram a pension of £50 per year as King’s Botanist for North America, a post he held until his death.

With this position, Bartram’s seeds and plants also went to the royal collection at Kew Gardens.

Bartram also contributed seeds to the Oxford and Edinburgh botanic gardens.

Above: King George III (1738 – 1820)

Most of Bartram’s many plant discoveries were named by botanists in Europe.

He is best known today for:

- the discovery and introduction of a wide range of North American flowering trees and shrubs, including kalmia, rhododendron and magnolia species

- introducing the Dionaea muscipulia or Venus flytrap to cultivation

- the discovery of the Franklin Tree (Franklinia alatamaha) in southeastern Georgia in 1765, later named by his son William Bartram.

Bartram’s name is remembered in the genera of mosses, Bartramia, and in plants such as the North American serviceberry, Amelanchier bartramiana, and the subtropical tree Commersonia bartramia (Christmas Kurrajong) growing from the Bellinger River in coastal eastern Australia to Cape York, Vanuatu and Malaysia.

Above: Amelanchier bartramiana (Bartram’s mountain juneberry)

Above: Commersonia bartramia (Bartram’s Christmas kurrajong)

Elizabeth Blackwell (1707 –1758)(née Blachrie) was a Scottish botanical illustrator and author who was best known as both the artist and engraver for the plates of “A Curious Herbal“, published between 1737 and 1739.

The book illustrated many odd-looking and unknown plants from the New World, and was designed as a reference work on medicinal plants for the use of physicians and apothecaries.

Elizabeth Blachrie was the daughter of a successful Scottish merchant in Aberdeen and was trained as an artist.

She secretly married her cousin, Alexander Blackwell (1709 – 1747), a Scottish doctor and economist and settled in Aberdeen where he maintained a medical practice.

Although his education was sound, his qualifications were questioned, leading to the young couple’s hasty move to London, fearing charges that Alexander was practicing illegally.

In London, Alexander became associated with a publishing firm, and having gained some experience, established his own printing house, despite not belonging to a guild nor having served the required apprenticeship as a printer.

He was charged with flouting the strict trade rules, and heavily fined, forcing him to close his shop.

By now Elizabeth was destitute.

Because of Alexander’s lavish spending and the fines that had been imposed, the couple were heavily in debt – Alexander found himself in debtor’s prison.

With her husband in gaol, a household to run, a child to care for, and with no income, the situation was desperate.

She learned that a herbal was needed to depict and describe exotic plants from the New World.

She decided that she could illustrate it, and that Alexander, given his medical background, could write the descriptions of the plants.

As she completed the drawings, Elizabeth would take them to her husband’s cell where he supplied the correct names in Latin, Greek, Italian, Spanish, Dutch and German.

Unlike her husband, Elizabeth was untrained in botany.

To compensate for this, she was aided by Isaac Rand, then curator of the Chelsea Physick Garden, where many of these new plants were under cultivation.

At Rand’s suggestion, she relocated near the Garden so she could draw the plants from life.

In addition to the drawings, Elizabeth engraved the copper printing plates for the 500 images and text, and hand-coloured the printed illustrations.

The first printing of A Curious Herbal met with moderate success, both because of the meticulous quality of the illustrations and the great need for an updated herbal.

Physicians and apothecaries acclaimed the work and it received a commendation from the Royal College of Physicians.

A second edition was printed 20 years later in a revised and enlarged format in Nuremberg by Dr. Christoph Jacob Trew, a botanist and physician, between 1757 and 1773.

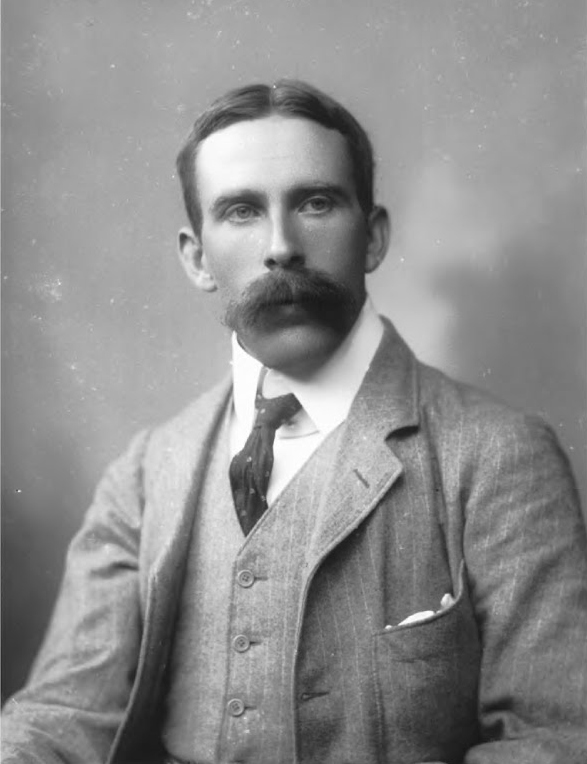

Above: Christoph Jacob Trew (1695 – 1769)

Revenue from the book led to Alexander’s release from prison.

However, within a short while debts again accumulated, forcing the couple to sell some of the publication rights to the book.

Alexander also became involved in several unsuccessful business ventures, and eventually left the family to start a new life in Sweden.

Alexander Blackwell arrived in Sweden in 1742 and carried on with agricultural experiments he had started when in Aberdeen.

These included the breeding of horses and sheep and dairy management.

His achievements were recognised and he was appointed court physician to Frederick I of Sweden.

Above: Frederick I (1676 – 1751)

Blackwell attempted to strengthen the diplomatic ties between Great Britain, Denmark and Sweden.

As Great Britain had no ambassador in Sweden, he contacted a Minister in Denmark.

On circumstantial evidence he was accused of conspiracy against the Crown Prince.

He was tried and sentenced to be decapitated.

He remained in good spirits to the last – at the block, having laid his head wrong, he remarked that since it was his first beheading, he lacked experience and needed instruction.

On 9 August 1747 he was executed as his wife was leaving London to join him.

Little is known of Elizabeth Blackwell’s later years.

She was buried on 27 October 1758 and her grave is at All Saints Church in Chelsea.

Blackwell’s “A Curious Herbal“ has featured on the British Library website as a “classic of botanical illustration.”

William Hudson (1730 – 1793) was a British botanist and apothecary based in London.

Hudson was apprenticed to a London apothecary.

Hudson obtained the prize for botany given by the Apothecaries’ Company, a copy of John Ray’s Synopsis.

But he also paid attention to mollusca and insects.

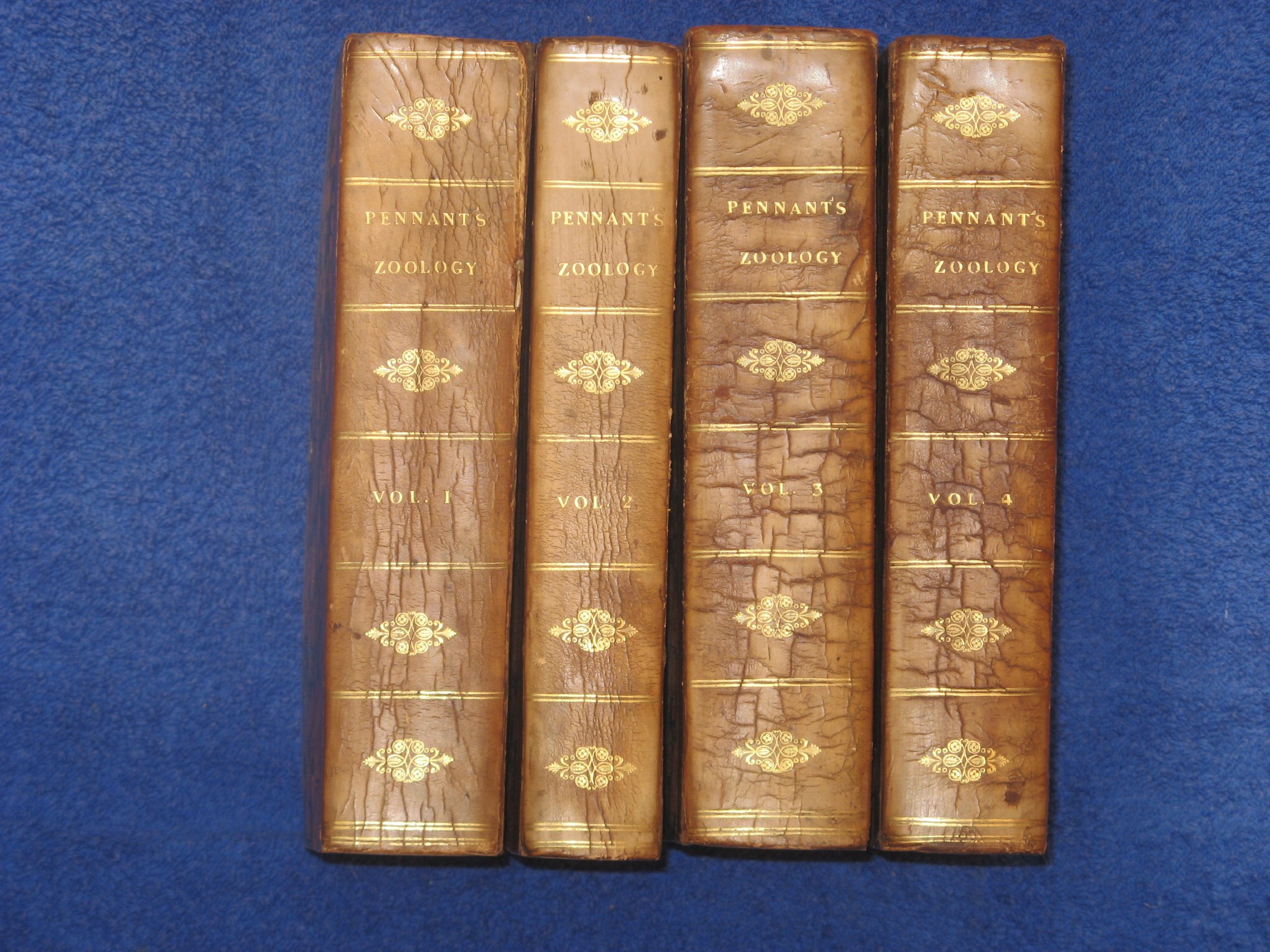

In Thomas Pennant’s British Zoology, Hudson is mentioned as the discoverer of Trochus terrestris.

(Thomas Pennant (1726 – 1798) was a Welsh naturalist, traveller, writer and antiquarian.