Landschlacht, Switzerland, 26 August 2018

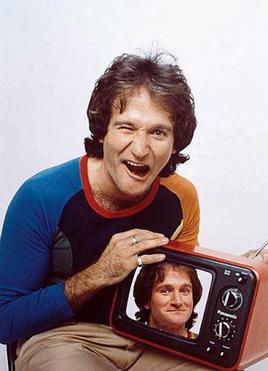

There is something about the politics of a number of nations today (the United States, North Korea, the Philippines, Venezuela) that reminds me again and again of the late Italian Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini.

Above: Il Duce Benito Mussolini (1883 – 1945)

I have written about Mussolini before – his birth and his youth, his exile in Switzerland, his rise to power, his reign as Il Duce, his fall from power, his temporary reprieve through German assistance, his capture and his death – (See Canada Slim and the Apostle of Violence) – when speaking of the Lake Como town of Dongo and the village of Giulino de Mezzegra.

Above: Dongo, where Mussolini was captured while fleeing to Switzerland

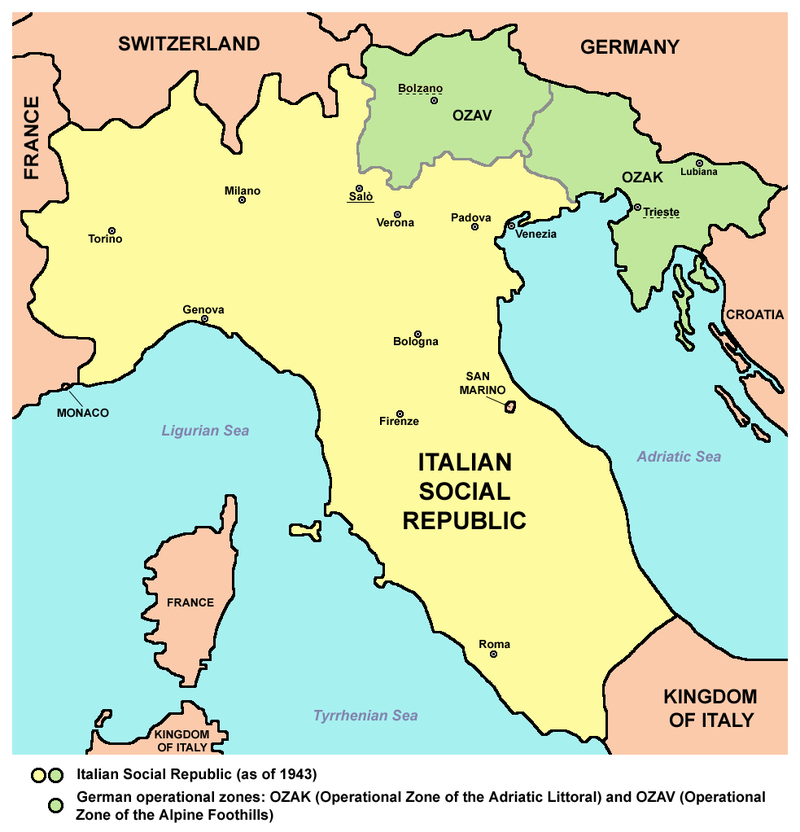

But I feel the need to speak of him again for we (the wife and I) visited the Lake Garda town of Salò which served as Mussolini’s de facto capital of the Italian Social Republic (23 September 1943 – 25 April 1945), a German puppet state of the Third Reich.

How did a man who once possessed absolute power over the whole of Italy (28 October 1922 – 25 July 1943) find himself reduced to being a mere figurehead for Nazi Germany?

And could one get a sense of that by visiting Salò over half a century later?

Salò, Lake Garda, Italy, Sunday 6 August 2017

Salò is one of the most important commercial and tourist centres of Lago Garda.

It lies in a spacious, seductive gulf on the slopes of Monte San Bartolomeo.

From the hills, resplendent in villas and olive yards, the viewer is rewarded by the grand immensity and glory of the Lake.

Above: Aerial view of Salò

According to a legend, Salò was founded by the Etruscan Queen Salonica.

There are some traces of the Roman colony Pagus Salodium: in the Lugone necropolis at via Sant’ Jago and findings of vase flasks and funeral steles in the Civic Archaeological Museum within the Communal Palace.

In 1377 Beatrice della Scala, Bernabó Visconti’s wife, chose Salò as the capital of Magnifica Patria (“the Magnificent Homeland“).

Above: Bernabo Visconti (1323 – 85) and Beatrice della Scala (1331 – 84)

Beatrice had walls propped up and a new castle built, of which sadly nothing remains.

On 13 May 1426, after a long period of war, the towns of the western bank of Lake Garda spontaneously joined the Republic of Venice wherein they would remain for the following three centuries.

Above: Winged lion column of St. Mark (symbol of Venice)

Sansovino built the Palace of the Captain Rector (now the town hall) and during the 15th and 16th centuries the Duomo (Cathedral) took form.

Among the famous men who were native to Salò we must remember:

- Gaspare Bertolotti (1540 – 1609) aka Gasparo da Salò, a famous maker of stringed instruments and inventor of the violin, whose bust is kept in the town hall.

- Above: The bust of Gasparo da Salò

- Pietro Bellotto (1625 – 1700), a painter who painted portraits for cardinals, popes and dukes and who after wandering from court to court he returned to Lake Garda to die

- Above: The Old Pilgrim, by Pietro Belloto

- Ferdinando Bertoni (1725 – 1813), composer, organist and prolific writer of church music and 70 operas

- Above: Fernando Bertoni

- Marco Enrico Bossi (1861 – 1925), composer, organist and music teacher, who established the standards of organ studies still used in Italy today and made numerous international organ recital tours

- Above: Marco Enrico Bossi

- Sante Cattaneo (1739 – 1819), painter known for his religious painting

- Angelo Zanelli (1879 – 1942), sculptor who created the large Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and the statue of Goddess Rome

- Luigi Comencini (1916 – 2007), film director known for his Commedia all’italiana (Italian-style comedy) movies:

- La bella di Roma (The Belle of Rome)

- Tutti a casa (Everybody Go Home)

- La ragazza di Bube (Bebo’s Girl)

- Incompreso (Misunderstood)

- Le avventure di Pinocchio (The Adventures of Pinocchio)

- Lo scopone scientifico (The Scientific Cardplayer)

- La donna della domenica (The Sunday Woman)

- Buon Natale…buon anno (Merry Christmas…Happy New Year)

- Un ragazzo di Calabria (A Boy from Calabria)

- La storia (History)

- Voltati Eugenio (Turn Around Eugenio)

- L’ingorgo (Traffic Jam)

- Signore e signori, buonanotte (Good Night, Ladies and Gentlemen)

- Quelle strane occasioni (Strange Occasion)

- Delitto d’amore (Somewhere Beyond Love)

- Senza Sapere niente di lei (The Unknown Woman)

- Infanzia, vocazione e prime esperienze di Giacomo Casanova, veneziano (Giacomo Casanova: Childhood and Adolescence)

- Il nostro agente Natlino Tartufato (Italian Secret Service)

- Le bambole (The Dolls)

- Il commissario (The Police Commissioner)

- A Cavallo della tigre (On the Tiger’s Back (US) / Jailbreak (GB))

- Und das am Montagmorgen (And That on Monday Morning)

- Le sorprese dell’amore (Surprise of Love)

- Mogli pericolose (Dangerous Wives)

- Mariti in città (Husbands in the City)

- La finestra sul Luna Park (The Window to Luna Park)

- Pane, amore e gelosia (Bread, Love and Jealousy)

- Pane, amore e Fantasia (Bread, Love and Dreams (GB)/ Frisky (US))

- La valigia dei sogni (Suitcase of Dreams)

- La Tratta delle bianche (Girls Marked Danger)

- Heidi

- Persiane chiuse (Behind Closed Shutters)

- L’imperatore di Capri (The Emperor of Capri)

- Proibito rubare (Hey Boy)

- Tre notti d’amore (Three Nights of Love)

- La mia Signora (My Wife)

- Il compagno Don Camillo (Don Camillo in Moscow)

- La bugiarda (Six Days a Week)

- Mio Dio come sono caduta in basso! (Till Marriage Do Us Part)

- Il gatto (The Cat)

- Above: Luigi Comencini

Comencini’s films tell wonderful stories:

- A missionary on his way to Africa has his suitcase stolen in Naples and, while trying to locate it, he comes to realize the suffering and poverty in the city needs his attention more.

- A beautiful gold digger, mistakes a waiter in a Neapolitan hotel, for an Arab prince.

- A woman searches for her missing sister in the morally degraded seaside of Genoa.

- A police chief wants to marry and selects a woman as his bride but she is already in love with his shy constable. Rejected, the chief turns his attention to the town midwife who returns his love but is hiding a secret….

- A junior officer is shocked when Germans storm the base where he is stationed and his fellow Italian officers simply want to go home.

- After receiving a tractor as a gift from a Soviet village, the mayor plans to twin the village with theirs. The priest tricks the Mayor into including him on the trip to Russia.

- An aging American millionairess journeys to Rome each year with her chauffeur to play cards with a destitute man and his wife. The annual scenario never changes: she donates the money so the Romans can play, then she wins the game shattering their dreams of escaping their poverty. But now the Roman couple’s daughter wants revenge….

- A girl raised by nuns marries a man only to discover on her wedding night that she married her brother….

- Thousands of motorists are stuck in a terrible traffic jam for 24 hours.

But as films go the Italian horror art film Salò: The 120 Days of Sodom, directed by Paolo Pasolini, is shockingly more frightening than the Italian Social Republic ever was.

Salò focuses on four wealthy, corrupt Italian libertines, during the time of the Social Republic, who kidnap 18 teenagers and subject them to four months of extreme violence, sadism, perversion, sex and fascism.

Salò has been banned in several countries because of all the graphic sex and violence and portrayals of rape, torture and murder.

Pasolini’s intentions were to use sex as a metaphor for the relationship between power and its subjects.

In Salò, the historically-informed mind is filled with confusion about a place so filled with contradictions:

Musicians and painters and movies that bring to brightest light the glorious potential that is man’s creative genius contrasted with a Führer’s puppet fascist frontier and a pornographic snuff film intended to somehow make a political statement revealing the darkest depths man can sink to.

But what can the visitor see today?

The Duomo di Santa Maria Annunziata has a memorable Renaissance portal by Gasparo Cairano and Antonio Mangiacavalli, 16th century paintings by Zenone Veronese, a polyptych of Paolo Veneziano and a Madonna and Saints by Romanino.

The Palazzo della Magnifica Patria is home to the Historical Museum of the Azure Ribbon, an exhibition of documents on Renaissance history, on Italy’s colonial wars, the Spanish Civil War and the resistance against fascism.

This latter part of the museum may feel ironic at first glance as Salò was the seat of government of Mussolini’s Nazi-backed puppet state, the Italian Social Republic.

Villa Castagna was the seat of the police headquarters, Villa Amedei was the head office of the Ministry of Popular Culture, Villa Simonin (today’s Hotel Laurin) was the seat of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and on via Brunati was located the Stefani Agency, Italy’s leading press agency during World War II.

Salò is a seismicity.

As the area around the lake is a seismic zone (a good place to measure earthquakes), in 1877 a meterological observatory and in 1889 a geophysical observatory (seismic station) were built, which became an important scientific research centre after the 1901 and 2004 earthquakes.

Biblical Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed by fire and brimstone.

Salò and Mussolini?

The former by earthquake one day?

The latter by gunfire.

Salò, despite its beauty, despite its importance, despite its hard work and industry, is a town branded by history, a place forever associated with a dying republic and a failed leader.

So as the mind meanders through the streets of Salò, let’s consider the man Mussolini and wonder how his personality compares with politicians of today.

What follows is a description of Il Duce as remembered by one of his contemporaries Luigi Barzini:

Above: Luigi Barzini, Jr. (1908 – 1984)

Mussolini grew up hating:

The Church, the army, the king, the police, the law, the rich, the well-educated, the well-washed, the successful, any kind of authority….

All the things he was later to defend.

He was a turbulent boy, determined to be first at everything, proud, quarrelsome, boastful, superstitious and not always very brave.

He picked quarrels for the sake of the fight.

When he won at games he wanted more than the stake.

When he lost he refused to pay.

He was expelled from two schools for having knifed two schoolmates.

Many of his companions hated him.

A few loved him dearly, fanatically, and followed him as their leader.

He is remembered for his harsh charm, his winning smile and his fierce loyalty to his friends and followers.

He was always persuaded that a great destiny was reserved for him.

Benito said to his mother when he was still a boy:

“One day I will make the earth tremble.”

He did.

Mussolini became a school teacher in 1901.

The following year he fled to Switzerland to avoid conscription.

At that time, the duty of a serious revolutionary.

Above: Police record of Benito Mussolini following arrest (19 June 1903)

He returned to Italy in 1904, as an heir had been born to the king and a general amnesty had been granted.

He became a village school teacher, served in the army (He turned out to be a good soldier, after all.), earned a new diploma as teacher of French in high schools, and did odd jobs as a journalist, socialist agitator and organizer.

Above: Young Benito Mussolini

He began to improve his oratory, slowly developing a technique which was to make him one of the best and most moving speakers in Italy.

He paid little attention to the logic and truth of what he said as long as it was energetic and stirring.

His gestures had rhythm and vigour.

He used short, staccato sentences, with no clear connexion between them, often with long and dramatic pauses, sometimes changing voice and expression in a crescendo of violence and ending in a tornado of abuse.

When the audience was carried away by his oratory he would sometimes stop and put to them a rheotrical question.

They roared their answer.

This established a sort of heated dialogue, through which the spectators became involved in decisions they had no time to meditate on.

By means of violent writing and incendiary eloquence, Mussolini rose in the socialist organization until, by 1912, he was made editor of the party newspaper, Avanti!.

Above: Benito Mussolini as editor of Avanti!

He was a very successful editor.

The paper’s circulation rose from 50,000 copies to 200,000 under his leadership.

The role of journalist was one of the few in his life he did not have to act.

He really was one, perhaps the best popular journalist of his day in Italy, addressing himself not to the sober cultured minority, but to the practically illiterate masses, easily swept by primitive emotions.

Those very qualities which made him an excellent rabble-rousing editor made him a disastrous statesman:

- His intuitive and superficial intelligence

- His capacity to oversimplify and dramatize

- A day-by-day interest only in the most striking events

- A strictly partisan point of view

- The disregard for truth, accuracy, objectivity and consistency when they interfered with his aims

- The talent for doing his job undisturbed by scruples, doubts or criticisms

- Above all, an instinctive ability to ride the emotional wave of the day, whatever it was, to know what people wanted to be told and by what low collective passions they would more easily be swept away.

He made strange grimaces when he talked, used violent and unprintable words, had an impatient temper….

Yet Mussolini managed to attract faithful friends and fanatical followers.

Some of whom clung to him until the end.

There was something about him that startled and fascinated almost everybody, including some of his enemies.

Most people who knew him well, who spoke frequently with him, who worked for him, were the victims of his inexplicable charm.

They fell in love with him, unreasoningly and blindly, ready to forgive him everything: his rudeness, his errors, his lies, his pretentiousness, his obstinacy and his ignorance.

One of the men who had worked for him since 1914, Manlio Morgagni, committed suicide in July 1943, after writing these words on a piece of paper:

“Il Duce has resigned.

My life is finished.

Viva Mussolini!”

Mussolini attracted many women.

He treated them roughly, as he had the peasant girls of Forli (where he grew up), taking them without preliminary explanation on the hard floor of his study or standing them against a wall.

Few sensed his timidity, his insecurity, his desire for admiration and affection.

Mussolini was obstinate, deaf to criticism, self-willed and suspicious, as well as erratic and indecisive most of the time, prone to adopt the most recent opinion he heard.

He was irresolute and afraid.

In the summer of 1914, Mussolini denounced warmongers.

He headed one of his violent articles:

“Who drives us to war betrays us“.

But then the journalist in him wavered when he felt he would lose followers by supporting the cautious government policy.

On 18 October 1914, without taking orders from or consulting the party leaders, Mussolini published an editorial urging war.

He was immediately dismissed from his job and expelled from the party in a stormy session.

He walked out crying dramatically:

“You hate me because you cannot help loving me!”

With foreign and Italian money, Mussolini started his own newspaper, Popolo d’Italia (People of Italy), which came out on 14 November 1914.

He immediately managed to gather more followers than he had had when editing Avanti! and more readers.

Italy entered World War I on 24 May 1915.

Mussolini went to war when he was called and served well as a corporal until he was wounded.

Above: Soldier Mussolini, 1917

After the war, when the frail structure of Italian political unity was endangered by civil strife, economic difficulties and the collapse of government, Mussolini used his paper to give vent to all his passions, to rally all the hot-headed veterans who found it difficult to return to dull civilian life, the very young men who felt that they had been cheated by not having been in the war, and all those who wanted a revolution, any kind of revolution.

On 23 March 1919, in Milan, he founded I Fasc (the League), a vague but determined organization which adopted a fiery and contradictory programme, so contradictory that it attracted dissatisfied and restless men from the right and left, anarchists and conservatives, businessmen and artists.

The confusion of the Fasci di combattimento (ex-servicemen league) reflected the disorderly but brilliant mind of Mussolini, his lack of principles and his constant inconsistency.

What Mussolini’s rheotric created, other men developed and their successes he would claim as his personal own.

Disgruntled anarchists across Italy violently seized regions and called them Fascist.

The March on Rome that would convince the King to make Mussolini Prime Minister wasn’t joined by the Fascist leader.

He arrived by train in Rome, borrowed a black shirt from one of the marchers and presented himself to the King as leader of the defiant assembly.

Even the black shirts themselves had been inspired by another man, Gabriele d’Annunzio, poet and self-proclaimed world’s greatest lover, who on 12 September 1919 led a band of 1,000 men to Fiume and conquered it for an Italy that had felt, despite being on the winning Allied side, that it had been cheated of territory and martial glory.

Above: Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863 – 1938)

And in one of history’s ironies, Hitler would borrow from Mussolini’s ideology his own brand of fascism and soon the student would far surpass and finally control the teacher.

Mussolini was dictator of Italy for two decades (1922 – 1943).

He was 39 when he seized power and 60 when he was forced to relinquish it.

Above: Mussolini, at start of his dictatorship

He had shaped Italy according to his wishes, organized according to his theories, staffed by men educated and selected by him.

His powers were limitless.

Where his legal prerogatives ended, his undisputed authority and immense personal prestige began.

He ran the only official political party, so invasive and widespread that it interfered with the daily habits of millions of people 24/7 from the cradle to the tomb.

He decided the contents of all written material.

He had no opposition.

Mussolini was sole legislator, judge, censor, policeman, ambassador, general, the head of government, president of the Grand Council, President of the Council of Ministers, Minister of the Interior, of Foreign Affairs, of the Army, the Navy and the Air Force, of Corporations.

What he didn’t run he controlled indirectly.

He was defeated by one man alone.

Himself.

He would become impotent in front of his enemies and of the arrogant ally he had encouraged and cultivated.

His grasp of world politics was over-rated.

He chose the wrong commanders, wrong strategies and wrong weapons.

He underestimated the will of the Italian people to suffer and die for a war they did not understand.

He believed his own propaganda.

He thought he had all the answers to all the riddles of the modern world.

He lacked raw materials, fuel and food to wage a long world war.

He lacked merchant ships to supply the far-flung theatres of war he had chosen to fight in.

His tanks were small, weak, slow, tin affairs, easily pierced by machine gun fire.

He had chosen them because they were cheaper and could buy them in bulk.

He said they were faster than the heavier models and more “attuned to the quick reflexes of the Italian soldier“.

He had no aircraft carriers.

His planes were good but too few to count and were not replaced fast enough.

His navy was efficient but not big or advanced enough to challenge the combined fleets he attacked.

They lacked radar which they never suspected existed.

What was missing in Italy wasn’t the courage or the will to fight but rather any kind of serious planning and organization behind the fighting men.

What had Mussolini really done with his time as dictator?

He promoted public works, built harbours, railways, roads, schools, autostrade, monuments, aqueducts, hospitals, irrigation and drainage networks, public buildings, bridges, etc.

But to get the exact measure of his achievements one must, first of all, subtract from the total all that would have been accomplished by any government in his place.

Subtract again how many projects that were just plain mistakes, decided for political and spectacular reasons rather than the hope of practical results.

Calculate how much money disappeared into the hands of dishonest contractors.

As a result, the sum total of Mussolini’s achievements is far out of proportion to the noise surrounding them, their fame and their moral cost.

What is the explanation for the inaction and ineffectiveness of Mussolini and why did he fail?

Mussolini was not stupid.

He was shrewd, quick to learn, wary, astute.

He could grasp a complex circumstance in a few minutes, face resolute opponents with success and usually take what intuitive decision any situation required.

The explanation of his failure is that he was not a failure.

He lost the war, his country, his mistress, his place in history and his life, but he succeeded in what he had always wanted to do.

It was not to make Italy safe and prsoperous.

It was not to organize Italy for a modern war and victory.

Mussolini had dedicated his life just to putting up a good show, a stirring show.

He played versatile and multi-faceted roles: the heroic soldier, the cold Machiavellian thinker, the Lenin-like leader of a revolutionary minority, the steely-minded dictator, the humanitarian despot, the Casanova lover, the Nietzschean superman, the Napoleonic genius and the socialist renovator of society.

He was none of these things.

In the end, like an old actor, he no longer remembered what he really was, felt, believed or wanted.

As a showman his success was incredible.

Mussolini was more popular in Italy than anybody had ever been and possibly ever will be.

His pictures were cut out of newspapers and magazines and pasted on the walls of poor peasant cottages.

Schoolgirls fell in love with him as with a film star.

His most memorable words were written large on village houses for all to read.

One of his followers exclaimed, after listening to Mussolini announce in May 1936 that Ethiopia had been conquered and that Rome had again become the capital of an empire:

“He is like a god.”

Another responded:

“Like a god?

No, no, he is a god.”

We laugh now when we see him in old newsreels.

His showmanship is like some wines which do not last or travel well, but which are excellent when consumed the year they are made in their native surroundings.

His technique was flamboyant, juvenile, ridiculous and highly effective.

Mussolini deceived the people.

He enjoyed a monopoly and was able to multiply his deceit by making good use of the newest communication techniques.

His slanted views and fabrications filled newspapers, posters, the radio, film screens, books, magazines and public discourse.

The majority of his captive audience believed most of what he wanted them to believe.

He loved a good show, enjoyed a good military parade, was comforted by a naval review and strengthened by a vast ocean of supporters in a city square.

He believed his own slogans.

He was amazed by the statistics he invented, thrilled by the boasts he made, stirred to tears by his own oratory.

He confused appearances for reality.

Truth was what it looked like and what most people liked to believe.

His show was always new and startling.

Only by keeping his public interested, thrilled, puzzled, frightened and entertained, could he make them forget the sacrifice of their liberty and their miserable poverty, unite them behind him, dishearten and divide his opposition, assure internal order and international prestige.

Mussolini was corrupted by his own spectacle and the people who surrounded him.

Great leaders, drunk with their own great importance and vast intelligence, think themselves infallible, surrounded by sychophants, all stumble and commit fatal mistakes.

Mussolini thought World War II was almost over when he entered Italy into it in June 1940.

He counted on the aid of Hitler in an emergency.

He trusted his own intuition and his luck.

But any reasonably prudent dictator should also have been prepared for unforeseen circumstances.

Mussolini was not.

He never knew what every military attaché in every foreign embassy in Rome knew.

Italy was ridiculously and tragically unprepared.

What blinded him?

He never even suspected that practically nothing was behind his show.

He never knew how really weak, disarmed and demoralized his country was.

He was badly informed, but he wanted to be badly informed.

The master of make-believe could not detect make-believe when practised by others on him.

His resistance to deception, which was never very strong, gradually dwindled and eventually disappeared altogether.

He needed bigger and bigger doses of flattery and deception each year.

In the end, the most sickening and improbable lies, as long as they adulated his idea of himself and confirmed his prejudices, seemed to him the plain and unadorned expression of objective truth.

In the end, Mussolini lived within his own private imaginary world of his own making.

He was shown only the things and the people that would please and comfort him.

Everything else was efficiently hidden.

The technique was so smooth that it even deceived Hitler.

Hitler’s favourable opinion of Mussolini, of Italian military preparations and the people’s devotion to the régime and to the Axis, made him commit several miscalculations which cost Germany the war.

Hitler had taken a big risk when he attacked Russia and tried to fight the war on two fronts, but he had a reasonable chance of winning despite heavy odds.

Hitler believed that he lost the Russian campaign because he had started four weeks too late.

He was four weeks too late because he wasted time to rescue the Italians bogged down in Albania in Mussolini’s ill-prepared attack on Greece.

Mussolini fell from power on 25 July 1943.

The allied armies had invaded Sicily only a few days before, all overseas possessions were lost, the Italian army had been destroyed in Russia, in the Balkans and in Africa, Italy was battered and paralysed by massive air bombardments, Germans were retreating.

All the big Fascist chiefs took part in a fateful meeting of the Grand Council and demanded that the command of all armed forces be turned over to the King.

Mussolini pleaded with them, cajoled them, threatened them and finally accepted his demotion.

The following day King Victor Emmanuel received Mussolini in his private villa and ordered his arrest.

There was no Fascist revolt when the news spread.

No faithful followers rose in arms.

Nobody kept the Fascist oath:

“I swear to defend the revolution with my blood.”

Nothing happened.

The show was over.

That’s all.

The people rejoiced simultaneously, for Mussolini had cost them much.

Mussolini was transported here and there in search of a place the Germans could not reach, to some islands at first, then to a ski resort hotel in the mountains of Abruzzi.

The Germans found him anyway, in spite of the fact that there was no road to the hotel and only a cable railway connected it with the lowlands.

They used gliders.

Mussolini arrived at Hitler’s headquarters, thanked his liberator, donned his old uniform and was named president of the puppet régime, the Italian Social Republic.

Mussolini’s capital was in Salò, comfortably on the direct road to the Brenner Pass, in case of sudden retreat to Switzerland.

As puppet president, Mussolini’s life was dismal.

He knew everything was lost.

He was a failure.

He had plunged Italy into the wrong war, at the wrong time, with practically no weapons.

The few moral and materialistic resources which existed, including the heroic courage of thousands of soldiers, were squandered by an amateur strategist who wanted to show his ally that he too was a mastermind.

Mussolini paid no attention to current affairs, read many books, wrote an enormous quantity of insignificance.

He was interested in only one thing:

How history would see him.

He knew the end had come.

Mussolini decided to trust his art as an actor: to disguise himself and flee.

He made up his mind to go directly to Switzerland, without wasting time in futile and bloody heroics, carrying all his money and documents to defend himself if he were tried as a war criminal.

On the road to Switzerland, he was found and arrested.

On 25 April 1945, Mussolini was executed and his body hung on display above a Milan petrol station.

Above: Mussolini (second from left)

Even in disgrace and death Mussolini had put on a public show.

In our journeys through Lombardy and around and amongst the northern Italian lakes, we neither sought out nor were overly interested in the life of this man over half a century deceased, but somehow Mussolini’s legacy quietly lingers here.

We would drive through Brenner Pass and later find ourselves spontaneously detour our Lake Como travels to the ornate gate of the pompous villa in the tiny village where he was executed, fascinated by the morbidity of everything.

Now on our homeward journey along the shores of Lake Garda we once again encounter the dark spectre of the man-monster that was Mussolini.

Salò once the home of musical genius and artistic endeavour seems now reduced to the embarrassing legacy of failed Fascist capital and unsavoury snuff film locale.

The August sun and horrid humid air seems somewhat chilled by the ghosts of the past.

Only the ignorant feel bliss here.

I wonder where and when the next dark Salò will be:

Somewhere in America?

Deep within North Korea?

On an island of the Philippines?

A village in Venezuela?

And as the world burns someone plays the violin….

Above: Coat of arms of the Italian Social Republic (or the Republic of Salò)

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / The Rough Guide to Italy / Lonely Planet Italy / Luigi Barzini, The Italians / R.J.B. Bosworth, Mussolini