Eskişehir, Türkiye

Friday 19 April 2024

“In the morning paper I come across two small events that together seem significant.

The black singer Paul Robeson was supposed to give a recital in Peoria.

At the last minute, the concert was cancelled on the pretext that Robeson is a Communist.

The authorities insist that they didn’t refuse to give him access to the hall because he is Black, but because he is a Communist.

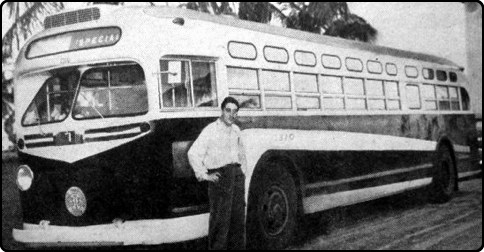

Above: American actor / athlete / bass-baritone concert singer / writer / civil rights activist Paul Robeson (1898 – 1976)

Elsewhere, an amusing episode just reached its conclusion.

Several weeks ago, a bus driver with a bus full of passengers travelling along some avenue got the bright idea to bypass all the stations and the terminal and to head out onto the highway amid his passengers’ panicked protests.

He let them out in the end, then calmly continued on his way to Florida.

When stopped and questioned, he cheerfully declared:

“That route was too monotonous.

I have always wanted to see Florida.

One fine morning, I said to myself:

‘Why not go to Florida?’

So I went.”

The driver has become a popular hero.

Although he had been fired, he went back to work yesterday amid ovations.

He was interviewed as well as photographed a hundred times.

In all the papers he is seen laughing through the windshield of the new bus he has just been given.

Perhaps such a fantasy is conceivable only in New York.

Friends have told me that nothing similar could happen, for example, in Chicago.

But even if they are incapable of doing it themselves, all Americans adore these uninhabited actions in which they see ready proof of their love of freedom.

The driver is a “character”, an original who has openly demonstrated that individualism America is so proud of.

And certainly in France he would never have been reinstated in his job.

Above: Bus driver William Cimillo (1909 – 1975)

It is true that America is much more indulgent of sudden whims and impulses that do not seriously challenge its authority.

I knew a pious and capable mother whose children were envied by all their little friends because they were allowed to climb trees, fight with one another and stick their tongues at their old teachers.

When they grew up, all the daughters docilely married the husbands chosen for them and the sons entered careers approved by their parents.

The pleasure and pride they found in their independence had made them even more submissive prey in their parents’ hands.

The bus driver would certainly laugh in the face of anyone who might doubt the freedom of American citizens.

Above: William Cimillo

Paul Robeson, however, didn’t want to do anything eccentric.

He just wanted to sing.“

(Simone de Beauvoir, diary entry of 19 April 1947)

Above: French philosopher / writer / activist Simone de Beauvoir (1908 – 1986)

William Cimillo was a New York City bus driver back in the 1940s.

He was a hard-working guy, never complained, and was even recognized for his exemplary work ethic.

Above: Empire State Building, New York City

But eventually, the daily grind was just a little too much for Cimillo, and in 1947, he left his route and drove south, heading straight for Florida in his bus.

He stopped in New Jersey for a bite to eat.

Above: State flag of New Jersey

He parked in front of the White House and took a look around DC.

He even picked up a hitchhiking sailor along the way.

He was arrested for the theft of the bus, but amid public acclaim for Cimillo the charges were dropped.

He resumed his job, unventfully driving New York City buses until his retirement sixteen years later.

Collect fares, hand out transfers, navigate traffic — like most jobs, driving a city bus is pretty routine.

That’s why William Cimillo, 37, a married father of two from the Bronx who had been driving a bus for 16 years, became fed up.

“Day in and day out it was the same old grind.

He was a slave to a watch and a schedule,” reported the Brooklyn Eagle.

Boredom led to daydreaming.

Cimillo wondered what it would be like if he “disobeyed the rules and forgot to look at his watch and did not get to that street corner at the right time,” wrote the Eagle.

One morning in March 1947, something came over him as he pulled away from the garage to start his shift on the BX15 route along Gun Hill Road.

“‘All of a sudden I was telling myself, baby, this is it.

I left that town in a hurry.

Somehow, I didn’t care where I went.

I just turned the wheel to the left, and soon I was on Highway 1, bound for Florida.’”

He was a hard-working guy, never complained, and was even recognized for his exemplary work ethic.

But eventually, the daily grind was just a little too much for Cimillo, and in 1947, he left his route and drove south, heading straight for Florida in his bus.

William Cimillo had been picking up passengers in the Bronx for 17 years.

Cimillo was a family man who worked for the NYC Surface Transportation System, and every day was the same.

“Up and down, every day,” he once told a TV interviewer, “the same people, the same stops, nickels, dimes, transfers, and — well, this morning, I thought I’d try something different.”

Tired of the same old routine, fed up with New York traffic, and probably feeling pressure to pay off some gambling debts, Cimillo decided he’d had enough.

Instead of sticking with his daily routine, he headed his bus south, going nowhere in particular.

Above: William Cimillo

For two weeks no one heard from Cimillo, not his company nor his wife and two children.

Speculation that his bus was hijacked (by someone other than Cimillo) or he had an unreported accident was in the minds of his employers and family.

After two weeks, the SFC finally got word from Cimillo in the form of a Western Union telegram requesting $50.

The request came from Hollywood, Florida.

Above: Hollywood, Florida

The STC decided to send a pair of police officers instead of the $50 and a mechanic to Florida to apprehend Cimillo and bring him back to New York City.

Cimillo never notified his family.

Instead his oldest son Richard saw his father on-screen in a matinee newsreel in the movie theater.

Three days later, he was in Hollywood, Florida, where he stopped for a night-time swim.

Cimillo was totally free and strapped for cash.

Hoping to make a few bucks, he wandered into a nearby racetrack, but when that didn’t pan out, he telegrammed his boss in New York, asking for $50.

And that’s when the cops showed up.

William Cimillo was under arrest for stealing a bus.

Two New York detectives and a mechanic were sent to fetch the runaway driver and his bright red bus, but according to Cimillo, the mechanic couldn’t really drive the darn thing.

Worried they’d end up in a ditch, the officers decided Cimillo should drive them back to New York.

And when they arrived, William Cimillo discovered he’d become a legend.

People across the country sent him fan mail, newspapers portrayed him as a working-class hero, and his bus-driving buddies raised enough cash to cover his legal expenses.

Realizing they were the bad guys here, the Surface Transportation System decided not to prosecute.

In fact, they gave Cimillo his job back, and when he showed up for work, everybody in the Bronx wanted to ride his route.

On one occasion, over 300 high school girls mobbed his bus, demanding an autograph.

And Hollywood (California) almost turned his story into a movie, starring Elizabeth Taylor as a totally fictional beauty queen who joined Cimillo on his wacky roadtrip.

For some reason, the movie was never made.

Above: English actress Elizabeth Taylor (1932 – 2011)

For the rest of his life, Cimillo was something of a superstar, but he never pulled any more wild stunts.

Instead, he kept on driving that bus for 16 more years before finally passing away in 1975.

Those three crazy days in 1947 were more than enough adventure for William Cimillo.

William Cimillo is buried in the grand Old St. Raymond Cemetery, noted for its large, elegant entry gateway.

There, William shares a granite tombstone bearing the carved names of a host of his family members, all

nestled nearby in the family plot.

He had a son, Richard Cimillo, who became a firefighter and does not hesitate to tell of his Dad’s adventure.

No matter what a particular man does or how he spends his day, he has one thing in common with all other men:

He spends it in a degrading manner.

And he himself does not gain by it.

It is not his own livelihood that matters.

He would have to struggle far less, since luxuries do not mean anything to him anyway.

It is the fact that he does it for others that makes him so tremendously proud.

He will undoubtedly have a photograph of his wife and children on his desk and will miss no opportunity to hand it around.

It’s a big job gettin’ by with nine kids and a wife

Even I’ve been workin’ man, dang near all my life but I’ll keep workin’

As long as my two hands are fit to use

I’ll drink my beer in a tavern

And sing a little bit of these working man blues

But I keep my nose on the grindstone, I work hard every day

Get tired on the weekend, after I draw my pay

But I’ll go back workin’, come Monday morning I’m right back with the crew

I’ll drink a little beer that evening

Sing a little bit of these working man blues

Sometimes I think about leaving, do a little bummin’ around

Throw my bills out the window, catch me a train to another town

But I go back working, I gotta buy my kids a brand new pair of shoes

I’ll drink a little beer that evening

Cry a little bit of these working man blues, here comes workin’ man

Well, hey, hey, the working man, the working man like me

Never been on welfare, and that’s one place I will not be

Keep me working, you have long two hands are fit to use

My little beer in a tavern

Sing a little bit of these working man blues, this song for the workin’ man

No matter what a man’s job may be – bookkeeper, doctor, bus driver or managing director – every moment of his life will be spent as a cog in a huge and pitiless system – a system designed to exploit him to the utmost, to his dying day.

Above: Charlie Chaplin (1889 – 1977), Modern Times (1936)

It may be interesting to add up figures and make them tally – but surely not year in, year out?

How exciting it must be to drive a bus through a busy town!

But always the same route, at the same time, in the same town, day after day, year after year?

What a magnificent feeling of power to know that countless workers move at one’s command!

But how would you feel if one suddenly realized one was their prisoner and not their master?

“G’day, my name’s Tony

On behalf of myself and the coachline

I’d like to thank you for choosing to drive with us today

I’m a local, I hope I can impart some local knowledge

If you’ve got any questions don’t hesitate, just sing out

For those who are interested, there’s the Old Bridge, swaying away

Replaced by the New Bridge in 1972

Funny thing, the Old Bridge used to be called the New Bridge

Yeah, bit of a funny thing

Up ahead there’s the bronze of Bluey

A local sheepdog, who became a member of Regional Council

It was a bloody great day for dogs, not just here

But everywhere in the North Island

Here’s the town’s oldest street

That’s the Museum of Meat

There’s the town’s largest industry

That’s the sock factory, hence the giant sock”

The town hall

Note the mosaic wall

Well, there are 5, 600 tiles on that wall

I know, I counted them all

The local school, the local swimming pool

Which was opened by the Governor General

Back in 1952

Where I was caught with a friend aged 11, sniffing tractor fuel

We thought we were pretty cool, breaking them changing shed rules

But do you see up there?

The banner hanging in the air?

The Presbyterian Fair

Well, I never go, there’s too many Presbyterians there

But if you’re interested, the fair’s in the third weekend of August every year

But don’t bother entering the raffle

It’s always won by some kid of the Mayor

Do you hear that sound?

The town clock, heard from anywhere in town

Until 1960, it was a little place in Norway

We bought it for a hundred pounds

Rumor has it they sold it cheap because the chimes were too loud

But every time I hear that sound it makes me so proud

Look to your left, what a beautiful sight

It’s Paula, Paula Thompson, nee Paula Wright

Look at her hair, it’s still gorgeous, even now

Flowing like the Womahonga River

Which incidently, is to your right

And it’s the largest, in the area

In terms of volume

Everybody, look at Paula, look at Paula Thompson

I always thought I’d marry Paula

But some things just don’t work out that way

Well, that’s the most important thing you’ll learn on the tour today

That, and the fact there’ll be a toilet break

At the information center near the manmade lake

“Yeah, I’ll just ask you one favor

If you do see Paula in town later on

That you don’t mention the details of the tour

I’d appreciate that

Same goes for my wife, Gloria

You’ll recognize her

She looks a hell of a lot like Paula, actually

She often gets mistaken for Paula

But, um, well, she’s not Paula, that’s for sure, no”

Paula Thompson, born in ’54

To a family of four

To the family next door

Take me back next door

Paula Thompson, nee Paula Wright

That’s her old house, number 39

Number 41 was mine

If this old coach could go back in time

I’d drive to 1979

Take me back

Take me back, take me back

(Take, take, take, take me back)

Take me back, take me back

(Take, take, take, take me back)

Take me back, take me back, take me back, take me back, take me back, take me back

“Yeah, sorry about that

I always get a little bit emotional

On the corner of Rutherford and Brown Streets

But, um, that is truly the end of the tour

So mind your step, yeah, good on you“

We have long ceased to play the games of childhood.

As children, we become bored quickly and changed from one game to another.

A man is like a child who is condemned to play the same game for the rest of his life.

The reason is obvious:

As soon as he is discovered to have a gift for one thing, he is made to specialize.

Then, because he can earn more money in that field than other, he is forced to do it forever.

If he was good at arithmetic in school, if he had a “head for figures“, he will be sentenced to a lifetime of figure work as bookkeeper, mathematician or computer operator, for there lies his maximum work potential.

Therefore, he will add up figures, press buttons and add up more figures, but he will never be able to say: “I’m bored. I want to do something else!”

He will never be permitted to look for something else.

Driven, he may engage in a desperate struggle agaınst competitors, to improve his position and perhaps even become head clerk or managing director of a bank.

But isn’t the price he is paying for his improved salary rather too high?

A man who changes his way of life or rather his profession – for life and profession are synonymous to him – is considered unreliable.

If he does it more than once, he becomes a social outcast and remains alone.

I was a rebel from the day I left school

Grew my hair long and broke all the rules

I’d sit and listen to my records all day

With big ambitions of when I could play

My parents taught me what life was about

So I grew up the type they’d warn me about

They said my friends were just an unruly mob

And I should, get a haircut and get a real job

Get a haircut and get a real job

Clean your act up and don’t be a slob

Get it together like your big brother Bob

Why don’t you, get a haircut and get a real job?

I even tried that nine to five scene

I told myself that it was all a bad dream

I found a band and some good songs to play

Now I party all night, I sleep all day

I met this chick, she was my number one fan

She took me home to meet her mommy and dad

They took one look at me and said, “Oh, my God!

Get a haircut and get a real job!”

Get a haircut and get a real job

Clean your act up and don’t be a slob

Get it together like your big brother Bob

Why don’t you, get a haircut and get a real job?

I hit the big-time with my rock and roll band

The future’s brighter now than I’d ever plan

I’m ten times richer than my big brother Bob

But, he’s got a haircut, and he’s got a real job

Get a haircut and get a real job

Clean your act up and don’t be a slob

Get it together like your big brother Bob

Why don’t you, get a haircut and get a real job?

The fear of being rejected by society must be considerable.

Why else will a doctor (who as a child liked to observe tadpoles in jam jars) spend his life opening up nauseating growths, examining and pronouncing on human excretions?

Why else does he busy himself nıght and day with people of such repulsiveness that everyone else is driven away?

We praise the colo-rectal surgeon

Misunderstood and much maligned

Slaving away in the heart of darkness

Working where the sun don’t shine

Respect the colo-rectal surgeon

It’s a calling few would crave

Lift up your hands and join us

Let’s all do the finger wave

When it comes to spreading joy

There are many techniques

Some spread joy to the world

And others just spread cheeks

Some may think the cardiologist

Is their best friend

But the colo-rectal surgeon knows…

He’ll get you in the end!

Why become a colo-rectal surgeon?

It’s one of those mysterious things.

Is it because in that profession

There are always openings?

When I first met a colo-rectal surgeon

He did not quite understand;

I said, “Hey nice to meet you

But do you mind? We don’t shake hands.”

He sailed right through medical school

Because he was a whiz

Oh but he never thought of psychology

Though he read “Passages“

A doctor he wanted to be

For golf he loved to play

But this is not quite what he meant…

By eighteen holes a day!

Praise the colo-rectal surgeon

Misunderstood and much maligned

Slaving away in the heart of darkness

Working where the sun don’t shine!

Does a pianist who, as a child, liked to tinkle on the piano really enjoy playing the same Chopin nocturne over and over again all his life?

Above: Polish composer / pianist Frederic Chopin (né Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin) (1810 – 1849)

It’s nine o’clock on a Saturday

The regular crowd shuffles in

There’s an old man sitting next to me

Makin’ love to his tonic and gin

He says, “Son, can you play me a memory?

I’m not really sure how it goes,

But it’s sad and it’s sweet, and I knew it complete

When I wore a younger man’s clothes.”

La, la, la, de, de, da

La, la, de, de, da, da, da

Sing us a song, you’re the piano man

Sing us a song tonight

We’re all in the mood for a melody

And you’ve got us feelin’ alright

Now, John at the bar is a friend of mine

He gets me my drinks for free

And he’s quick with a joke or to light up your smoke

But there’s someplace that he’d rather be

He says, “Bill, I believe this is killing me.”

As a smile ran away from his face

“Well, I’m sure that I could be a movie star

If I could get out of this place.”

Oh, la, la, la, de, de, da

La, la, de, de, da, da, da

Now Paul is a real estate novelist

Who never had time for a wife

And he’s talkin’ with Davy, who’s still in the Navy

And probably will be for life

And the waitress is practicing politics

As the businessmen slowly get stoned

Yes, they’re sharing a drink they call loneliness

But it’s better than drinkin’ alone

Sing us a song, you’re the piano man

Sing us a song tonight

Well, we’re all in the mood for a melody

And you’ve got us feelin’ alright

It’s a pretty good crowd for a Saturday

And the manager gives me a smile

‘Cause he knows that it’s me they’ve been comin’ to see

To forget about Life for a while

And the piano, it sounds like a carnival

And the microphone smells like a beer

And they sit at the bar and put bread in my jar

And say, “Man, what are you doin’ here?“

Oh, la, la, la, de, de, da

La, la, de, de, da, da, da

Sing us a song, you’re the piano man

Sing us a song tonight

Well, we’re all in the mood for a melody

And you’ve got us feelin’ alright

Why else does a politician who as a schoolboy discovered the techniques of manipulating people successfully continue as an adult, mouthing words and phrases as a minor government functionary?

Does he actually enjoy contorting his face and playing the fool and listening to the idiotic chatter of other politicians?

Surely he must once have dreamed of a different kind of life.

Even if he became the President of the United States, wouldn’t the price be too high?

No, one can hardly assume men do all this for pleasure and without feeling a desire for change.

They do it because they have been manipulated into doing it.

Their whole life is nothing but a series of conditioned reflexes, a series of animal acts.

A man who is no longer able to perform these acts, whose earning capacity is lessened, is considered a failure.

He stands to lose everything – wife, family, home, his whole purpose in life – all the things, in fact, which gave him security.

A man who has lost his capacity for earning money is freed from his burden.

He should be glad about this happy ending.

But freedom is the last thing he wants.

Man is always searching for someone or something to serve, for only then does he feel secure.

Comfortably numb, living a life of quiet desperation.

Hello? (Hello? Hello? Hello?)

Is there anybody in there?

Just nod if you can hear me

Is there anyone home?

Come on now

I hear you’re feeling down

Well I can ease your pain

Get you on your feet again

Relax

I’ll need some information first

Just the basic facts

Can you show me where it hurts?

There is no pain, you are receding

A distant ship smoke on the horizon

You are only coming through in waves

Your lips move, but I can’t hear what you’re saying

When I was a child I had a fever

My hands felt just like two balloons

Now I’ve got that feeling once again

I can’t explain you would not understand

This is not how I am

I have become comfortably numb

I have become comfortably numb

Okay (okay, okay, okay)

Just a little pinprick

There’ll be no more, ah

But you may feel a little sick

Can you stand up?

I do believe it’s working, good

That’ll keep you going through the show

Come on it’s time to go

There is no pain, you are receding

A distant ship, smoke on the horizon

You are only coming through in waves

Your lips move, but I can’t hear what you’re saying

When I was a child

I caught a fleeting glimpse

Out of the corner of my eye

I turned to look but it was gone

I cannot put my finger on it now

The child is grown

The dream is gone

I have become comfortably numb

“Like the waters of the sea, tears have their level!“

(José Echegaray)

Above: Spanish mathematican / dramatist José Echegaray (1832 – 1916)

Men love to work.

Late in the evening if you drive through working men’s suburbs, you will always see garage lights on.

Inside, groups of men labour over old cars, lovingly modifying, repairing and maintaining late into the night.

Others are busy building furniture in their workshops or working in metal and wood.

These are mostly men who have worked hard all day in uninteresting jobs but who, with passion and intelligence, apply themselves at night to their real interests.

Among the middle classes, the focus shifts to “renovating” – that endless fixing-up of our dwellings that seems to fill the whole of the years from 25 to 50.

In other countries, a plethora of exotic and weird hobbies – from electric trains to rose breeding, guinea pigs to Shakespeare acting – seem to draw men out from the stifling ordinariness of their daytime lives.

Well, I get up at seven, yeah

And I go to work at nine

I got no time for livin’

Yes, I’m workin’ all the time

It seems to me

I could live my life

A lot better than I think I am

I guess that’s why they call me

They call me the workin’ man

They call me the workin’ man

I guess that’s what I am

‘Cause I get home at five o’clock

And I take myself out an ice cold beer

Always seem to be wonderin’

Why there’s nothin’ goin’ down here

It seems to me

I could live my life

A lot better than I think I am

I guess that’s why they call me

The workin’ man

Well, they call me the workin’ man

I guess that’s what I am

Well, they call me the workin’ man

I guess that’s what I am

Well, I get up at seven, yeah

And I’ll go to work at nine

I got no time for livin’

Yes, I’m workin’ all the time

It seems to me

I could live my life

A lot better than I think I am

I guess that’s why they call me

They call me the workin’ man

Well, they call me the workin’ man

I guess that’s what I am

They call me the workin’ man

I guess that’s what I am

“I have always made a respectable living, but I have not been willing to give up my life to getting the kind of money with which you can buy the best things in life.

I am stuck in business and routine and tedium.

I must live as I can, but I give up only as much as I must.

For the rest, I have lived and always will live my life as it can be lived at its best with art, music, poetry, literature, science, philosophy and thought.

I shall know the keener people of this world, think the keener thoughts and taste the keener pleasures as long as I can and as much as I can.

That is the real practical use of self-eduction and self-culture.

It converts a world which is only a good world for those who can win at its ruthless game into a world good for all of us.

Your education is the only thing that nothing can take from you in this life.

You can lose your money, your wife, your children, your pride, your honour and your life, but while you live you cannot lose your culture, such as it is.“

(Cornelius Hirschberg, quoted by Ronald Gross, The Independent Scholar’s Handbook)

If old age did not bring with it the placidity of living, what reward would be enough to console us for youth and life spent in struggles and sleepless nights?

The greatest heartbreak is to contemplate how the years fly away without peace arriving.

I was a mathematician by vocation, I did not see my death as likely, since in the demographic statistics, grief shows a much more intimate figure than colic, and I never feared to these, although I always ate very well.

(José Echegaray)

Above: José Echegaray

We know that for hundreds of thousands of years, men have admired each other and have been admired by women in particular, for their activity.

Men were called on to pierce the dangerous places, carry handfuls of courage to the waterfalls, dust the tails of the wild boars.

Men have been loved for their astonishing initiative, embarking on wide oceans, starting a farm in rocky country, imagining a new business, doing it skillfully, working with beginnings, doing what has never been done, boldly going where no one has gone before.

Working hard and enjoying it comes naturally to men.

Yet it has been somewhat debased.

“What a piece of work is a man!

How noble in reason!

How infinite in faculties!

In form and moving, how express and admirable!

In action, how like an angel!

In apprehension, how like a God.”

William Shakespeare put these words in Hamlet’s mouth, but he was definitely on to something.

Above: William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616)

Men have had the courage to fight and die for the causes they believe in.

Men have been picking up weapons and fighting tyranny and oppression for millennia.

And they continue to do so.

The fight over what is a “just war” and which class of men actually started the battle in the first place, continues to rage.

Yet, more often and more numerously it is men who must screw their courage to the sticking post and fire the bullets before any discussion is even had.

A man provides.

And he does it even when he’s not appreciated or respected or even loved.

He simply bears up and he does it.

Because he’s a man.

Men may collect the straws that break their own backs, but they do so with a lot of love and duty.

Men try their best to provide for the people they love even when the task is nigh on impossible and it breaks them or their spirit.

It makes men vulnerable to systems they may not have had a hand in.

Two years before he became the 26th president of the US, Theodore Roosevelt said:

“We do not admire the man of timid peace.

We admire the man who embodies victorious effort, the man who never wrongs his neighbour, who is prompt to help a friend, but who has those virile qualities necessary to win in the stern strife of actual life.“

Above: Theodore Roosevelt (1858 – 1919)

D.H. Lawrence described how in industrial England, the men working in the coal mines took satisfaction and found comradeship in their work and were proud of being good providers.

Then schooling was introduced and rather than working with their fathers, boys began going to school.

There they were taught by white-collared teachers that their fathers’ world – the sweaty difficult world of physical labour was demeaning and that by applying themselves the young boys could aspire to a clean, educated, “higher” world.

The fact that this “advancement” meant an adult life spent stoopedd at desks doing dreary clerical tasks was not really questioned.

One was “bettering oneself“.

There was something virtuous in being clean, in never exerting one’s body.

Above: English writer David Herbert “D. H.” Lawrence (1885 – 1930)

Powerful symbols soon divided men.

One of these was the necktie.

A tie symbolizes something very profound – a willingness to fit in or to submit.

It says:

“See, I am willing to go through the motions. I will be a good boy.”

At work a tie says: “I am willing to put up with this discomfort.” and therefore “I am willing to put up with other indignities and constraints to get and keep this job.”.

It is important to see a tie for what it is.

It is a slave collar.

Class is a funny thing.

Many men have long discovered too late that rising in the class hierarchy does not make you freer:

In fact, the reverse.

If you are a blue collar worker, the company wants your body but your soul is your own.

A white collar worker is supposed to hand over his spirit as well.

It is not just the tie – a whole uniform goes with it.

“Look out the window.

Tell me what you see….

Look at the people.

Tell me which ones are free.

Free from debt, anxiety, stress, fear, failure, indignity, betrayal?

How many wish they were born knowing what know now?

Ask yourself:

How many would do things the same way all over again?“

Above: Helen Rodin (Rosamund Pike) and Jack Reacher (Tom Cruise), Jack Reacher (2012)

There is a beautıful scene in the film, The Fringe Dwellers, where the Aboriginal men sit together making jokes about the poor white man spending his weekends mowing the lawn and washing the car.

In the US there is a slang term for the men who do the paperwork, attend to the boring details of the business world.

These men are called “suits“.

The millionaire in Pretty Woman strikes a deal and leaves the details to “the suits” to tidy up.

Suits (and the men who wear them) are characterized by their lack of colour, their lack of individuality.

Ride the commuter planes between cities any morning at 0700 or late in the evening and you will be amazed at the vast numbers of look-alike grey-faced men, moving endlessly to and fro across the country in the dreadful lifestyle of the “executive“.

They might be flying First or Business class.

They are first off the plane, into the Club Lounges, but no one in their right mind would envy them.

They are privileged eunuchs, leading a dry and joyless life.

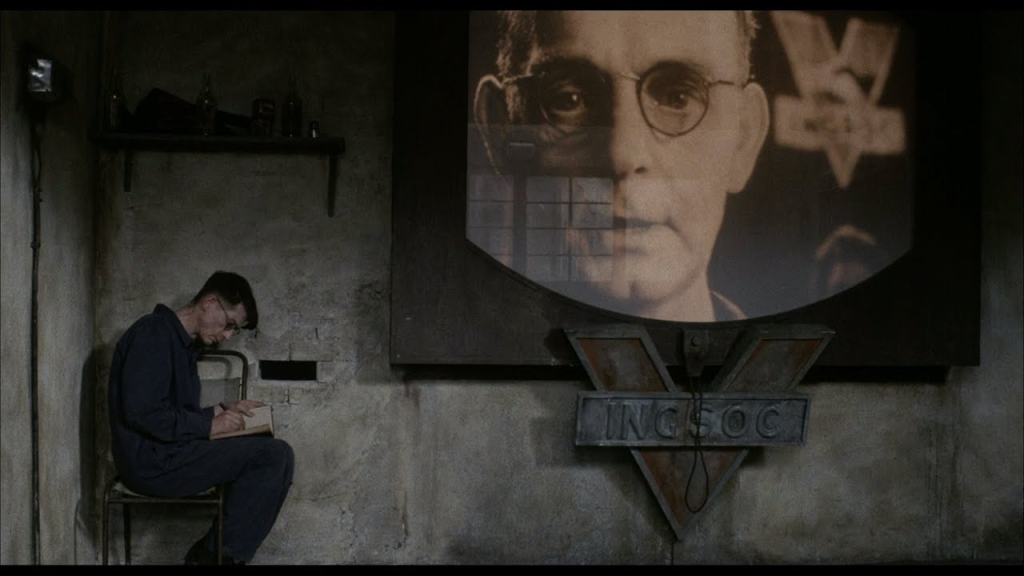

“He moved over to the window:

A smallish, frail figure, the meagreness of his body merely emphasized by the blue overalls which were the uniform of the Party.

His hair was very fair, his face naturally sanguine, his skin roughened by coarse soap and blunt razor blades and the cold of the winter that had just ended.

Outside, even through the shut window-pane, the world looked cold.

Down in the street little eddies of wind were whirling dust and torn paper into spirals, and though the sun was shining and the sky a harsh blue, there seemed to be no colour in anything, except the posters that were plastered everywhere.“

(George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four)

Above: Winston Smith (John Hurt), Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984)

It isn’t the fact of working that does harm.

Work is good – it is what men love to do.

It is the nature of the work that is the problem.

If you do a job that lacks heart, it will kill you.

The strongest predictor of life expectancy in a man is whether he likes his job.

Two elements – the lack of real purpose and the lack of personal control – are the main problems.

Our ancestors laughed as they worked and sang.

They enjoyed the rush of the hunt, the steady teamwork of digging for yams or the discovery of a honey-filled tree.

What any documentary or archival footage of preliterate people, you will see the same thing.

Life was often hard but it was rarely without laughter.

In time, though, cultures evolved away from the forest and the coast and into the village and the town.

We did the work that others commanded and it became a grind – increasingly repetitive.

It was a numbing of the human senses and a subjugation of ourselves beneath the need just to survive.

Work has become more comfortable but not more fulfilling.

It is still a separate compartment in life – something you tolerate in exchange for “real” living in the time left over from doing your job, getting to your job and recovering from your job.

Work today drives an unhealthy wedge into the very core of our life.

The time has come to heal it.

Most people today, men and women, do work they do not much like – jobs that are beneath them.

Since you have to work to purchase the good life, the aim is to find the best paying job you can tolerate.

That is what jobs are.

Why else would you do them?

With unemployment rates today, to have any job is seen as a privilege and being choosy is a sin.

We have to fight this selling-short of human potential.

The purpose of life is to find what you really love to do.

Have work that your heart is in.

Work that makes you jump out of bed in the morning, keen to get started.

I think of José Echegaray y Eizaguirre (1832 – 1916), a Spanish civil engineer, mathematician, statesman, and one of the leading Spanish dramatists of the last quarter of the 19th century.

He made important contributions to mathematics and physics.

He introduced Chasles geometry, Galois theory and elliptic functions to Spain.

He is considered the greatest Spanish mathematician of the 19th century.

Julio Rey Pastor stated:

“For Spanish mathematics, the 19th century begins in 1865 with Echegaray.”

In 1911, he founded the Royal Spanish Mathematical Society.

Above: José Echegaray

He was awarded the 1904 Nobel Prize in Literature “in recognition of the numerous and brilliant compositions which, in an individual and original manner, have revived the great traditions of the Spanish drama“.

He was born in Madrid on 19 April 1832.

His father, a doctor and institute professor of Greek, was from Aragon and his mother was from Navarra.

Above: Madrid, Spain

When he was 5 years old, his family moved to Murcia, due to his father’s work.

He spent his childhood in Murcia, where he finished his elementary school education.

It was there, at the Murcia Institute, where he first gained his love for mathematics.

Above: Murcia, Spain

“Mathematics forms a sauce that goes well with all the stews of the spirit.

They harmonize with music and art in general.

As if they are all harmonies, varieties in one form or another, which resolve into a high and beautiful unity.“

(José Echegaray)

Above: The Babylonian mathematical tablet Plimpton 322 (1800 BC)

While still a child he read Goethe, Homer and Balzac, readings that alternated with those of mathematicians like Gauss, Legendre, and Lagrange.

Above: German polymath / writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 – 1832)

Above: Bust of Greek poet Homer (8th century BC)

Above: French writer Honoré de Balzac (1799 – 1850)

Above: German mathematician Johann Carl Friedrich Gauß (1777 – 1855)

Above: Caricature of French mathematician Adrien-Marie Legendre (1752 – 1833)

Above: Italian mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange (né Giuseppe Ludovico Lagrangia) (1736 – 1813)

In order to earn enough money to attend the Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingeniería de Caminos, Canales y Puertos (Engineering School of Roads, Channels and Ports), he moved at the age of 14 to Madrid.

At the age of 20, he left the Madrid school with a Civil Engineering degree, which he had obtained as first in his class.

Above: Escuela de Ingenieros de Caminos, Canales_y_Puertos (Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Spain

He moved to Almeria and Granada to begin working at his first job.

Together with Gabriel Rodríguez he founded El Economista, a magazine in which he wrote numerous articles, thus beginning a journalistic activity that he would not abandon throughout his life.

In 1854 he began teaching a class at the engineering school, working as a secretary there also.

He taught mathematics, stereotomy, hydraulics, descriptive geometry, differential and physical calculus from that year until 1868.

From 1858 to 1860 he was also a professor at the Assistants’ School of Public Works.

In his career as a scientist and teacher he published many works on physics and mathematics.

His Problemas de geometría analítica (1865) and Teorías modernas de la física, Unidad de las fuerzas materiales (1867) were held in some regard.

Above: José Echegaray

He became a member of the Society of Political Economy, helped to found the magazine La Revista and took a prominent part in propagating free trade doctrines in the press and on the platform.

He was clearly marked out for office.

When the Glorious Revolution of 1868 overthrew the monarchy, he resigned his post for a place in the revolutionary cabinet.

Echegaray also entered politics later in his life.

As a founding member of the republican Radical Democratic Party, he enjoyed a career in the government sector, being appointed Minister of Education, of Public Works and Finance Minister successively between 1867 and 1874.

He retired from politics after the Bourbon restoration in 1874.

Above: Spanish Parliament, Madrid

Theatre had always been the love of José Echegaray’s life.

Although he had written earlier plays (La Hija natural (“The Natural Daughter“) and La Última Noche, both in 1867), he truly became a dramatist in 1874.

His plays reflected his sense of duty, which had made him famous during his time in the governmental offices.

Dilemmas centered on duty and morality are the motif of his plays.

He replicated the achievements of his predecessors of the Spanish Golden Age, remaining a prolific playwright.

He premiered 67 plays, 34 of them in verse, with great success among the public of the time, although devoid of literary value for later criticism.

He himself always maintained a distant attitude towards his works.

Echegaray had great prestige in Spain at the beginning of the 20th century, a prestige that reached the fields of literature, science and politics and a well-established fame in the Europe of his time.

His works were successful in cities such as London, Paris, Berlin and Stockholm.

Above: José Echegaray

His most famous play is El gran Galeoto (“The great galley slave“), a drama written in the grand 19th century manner of melodrama.

It is about the poisonous effect that unfounded gossip has on a middle-aged man’s happiness.

Echegaray filled it with elaborate stage instructions that illuminate what we would now consider a hammy style of acting popular in the 19th century.

Paramount Pictures filmed it as a silent with the title changed to The World and His Wife.

It was the basis for a later film The Great Galeoto.

His most remarkable plays are O locura o santidad (“Saint or Madman?“)(1877), Mariana (1892), El estigma (1895), La duda (1898) and El loco Dios (“God the fool“)(1900).

Above: José Echegaray

(Mariana is a woman tormented by her past:

Her mother abandoned the family out of passion for a man named Alvarado who later made her the object of abuse until she died.

That is why Mariana has developed a neurotic impulse of revenge and humiliation towards the entire male gender.

She includes poor Daniel, whom she deep down loves.)

Among his other famous plays are La esposa del vengador (1874) (“The Avenger’s Wife“), En el puño de la espada (1875) (“In the Sword’s Handle”), En el pilar y en la cruz (1878) (“On the Stake and on the Cross“) and Conflicto entre dos deberes (1882) (“Conflict of Two Duties“).

Above: José Echegaray

El hijo de Don Juan (“Don Juan’s son“) (1892):

The young Lázaro loses his mind as a result of a strange illness transmitted to him by his father Don Juan, a man who led a totally dissolute life.

Mancha que limpia (“The stain that cleans“) (1895):

Matilde is a woman driven mad by jealousy over her beloved Fernando’s marriage to Enriquita, a perfidious woman who is unfaithful to him.

Matilde murders the woman and her husband pleads guilty to the crime in defense of her honour.

La calumnia por castigo (“Slander for punishment“) (1897) focuses on the diatribe of whether absolute rehabilitation exists in the criminal order.

Along with the Provençal poet Frédéric Mistral, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1904, after having been nominated that year by a member of the Royal Spanish Academy, making him the first Spaniard to win the prize.

Above: French writer Frédéric Mistral (1830 – 1914)

“I choose a passion, I take an idea, a problem, a character and I infuse it, like dense dynamite, deep into a character that my mind creates.

The plot, the character is surrounded by a few dolls that in the world either wallow in the filthy mud or warm themselves in the Phoebean light.

The fuse lit.

The fire is prepared, the cartridge bursts without remedy, and the main star is the one who pays for it.

Although sometimes also in this siege that I put on art and that flatters instinct, the explosion catches me in the middle!“

Above: José Echegaray

José Echegaray maintained constant activity until his death on 14 September 1916 in Madrid.

His extensive work did not stop growing in his old age:

In the final stage of his life he wrote 25 or 30 mathematical physics volumes.

At the age of 83 he commented:

“I cannot die, because if I am going to write my mathematical physics encyclopedia, I need at least 25 more years.”

Above: José Echegaray

Known as a university town, Eskişehir Technical University, Eskişehir Osmangazi University and Anadolu University are based in Eskişehir.

The vast majority of my Wall Street English classes are either students presently enrolled in one of these univerisities or are alumni of these institutions.

Of these three universities and their combined 35 faculties, all have produced 80% of Wall Street English Eskişehir’s student body:

Engineers.

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the limitations imposed by practicality, regulation, safety and cost.

The word engineer (Latin ingeniator) is derived from the Latin words ingeniare (“to contrive, devise“) and ingenium (“cleverness“).

The work of engineers forms the link between scientific discoveries and their subsequent applications to human and business needs and quality of life.

A professional engineer is competent by virtue of his/her fundamental education and training to apply the scientific method and outlook to the analysis and solution of engineering problems.

He/she is able to assume personal responsibility for the development and application of engineering science and knowledge, notably in research, design, construction, manufacturing, superintending, managing, and in the education of the engineer.

His/her work is predominantly intellectual and varied and not of a routine mental or physical character.

It requires the exercise of original thought and judgment and the ability to supervise the technical and administrative work of others.

His/her education will have been such as to make him/her capable of closely and continuously following progress in his/her branch of engineering science by consulting newly published works on a worldwide basis, assimilating such information, and applying it independently.

He/she is thus placed in a position to make contributions to the development of engineering science or its applications.

His/her education and training will have been such that he/she will have acquired a broad and general appreciation of the engineering sciences as well as thorough insight into the special features of his/her own branch.

In due time he/she will be able to give authoritative technical advice and assume responsibility for the direction of important tasks in his/her branch.

“Medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life.

But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.“

(Dead Poets Society)

I am not anti-engineering.

As much I respect engineers and all that they do, as students I have found them to be more in love with and more comfortable with machines than they are with people.

The engineers I have mingled with have, with rare exception, been resistant to reading, to writing, to homework or conversation beyond what is unavoidably necessary.

Certainly, the history of literature has seen engineers quite capable of producing poetry, prose and plays, but they seem to me to be the exception rather than the rule.

This is what compels my curiosity regarding Echegaray, for he possessed a certain quality that I believe is crucial for everyone:

Passion for all that a person does.

I am reminded of the Wim Wenders film Perfect Days.

Hirayama (Kōji Yakusho) works as a public toilet cleaner in Tokyo’s upscale Shibuya ward, across town from his modest home in an ungentrified neighborhood east of the Sumida River.

He repeats his structured, ritualized life every day, starting at dawn.

He dedicates his free time to his passion for music, which he listens to in his van to and from work, and to his books, which he reads every night before going to sleep.

He reads stories by William Faulkner and Patricia Highsmith and the essays of Aya Kōda.

Above: American writer William Faulkner (1897 – 1962)

Above: American writer Patricia Highsmith (née Mary Patricia Plangman) (1921 – 1995)

Above: Japanese writer Aya Kōda (1904 – 1990)

Hirayama chooses the music he listens to, Wenders said:

“Maybe he’s clinging to the past.

But he’s clinging a little bit also to his youth and he loves that music.

He chooses in the morning exactly what he’s going to listen to that day.

And it’s not random.“

Above: German filmmaker / playwright Wim Wenders

His dreams are shown in flickery impressionistic sequences at the end of every day.

Hirayama is also very fond of trees and spends time gardening and photographing them.

He has a sandwich every day in the shade under trees in the grounds of a shrine and takes photos of their branches and leaves.

His pride in his work is apparent by its thoroughness and precision.

Hirayama’s young assistant, Takashi (Tokio Emoto), is often late, loud and not as thorough.

One day, a young woman named Aya (Aoi Yamada) stops by the public toilet Takashi is cleaning, so he hurries to finish.

Takashi tries to leave with Aya, but his motorbike will not start, so he convinces Hirayama to let him use his van.

When Aya says Takashi can stay with her as she works at a girls bar, he complains loudly that he is broke.

Above: Signage for hostess bars in Kabukichō, Tokyo, Japan

Unbeknownst to Hirayama, Takashi slips Hirayama’s Patti Smith tape into Aya’s purse.

Takashi talks Hirayama into going into a shop to get some of his cassettes appraised.

When Takashi discovers how valuable they are, he urges Hirayama to sell, but Hirayama refuses, giving him some cash so he can take out Aya.

When Hirayama runs out of gas on the way home, he is forced to sell a cassette for gas money.

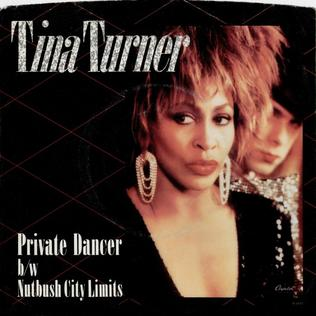

Above: American artist Patti Smith

Hirayama commences a tic-tac-toe game with a stranger after finding a piece of paper left hidden in a stall.

The game continues over the course of the film.

He exchanges furtive glances with a strange woman eating lunch one bench over.

Aya catches up with Hirayama to return the Patti Smith cassette.

She asks to play it in his van one last time and then gives him a thank-you kiss on the cheek, leaving him visibly startled.

On his free day, Hirayama does his laundry, takes the film with his tree photos to be developed, cleans his flat, buys a new book, and dines out at a restaurant where the female proprietor shares gossip with him.

Niko (Arisa Nakano), Hirayama’s niece, shows up unannounced, having run away from his wealthy estranged sister Keiko’s home.

He lets Niko accompany him to work during the next two days.

The two photograph the trees in the park and ride bikes together.

Eventually, Keiko (Yumi Asō) comes to pick up Niko in a chauffeured car.

Keiko tells him that their father’s dementia has worsened and asks whether Hirayama will visit him in the nursing home where he lives.

She says that he doesn’t recognize anything anymore and will not behave the way he did before.

Hirayama sorrowfully refuses but hugs his sister good-bye.

Before she leaves, she asks him whether he really cleans toilets for a living, and he says yes.

As they drive away, Hirayama begins to cry inconsolably.

The next day, Takashi quits without giving notice, leaving Hirayama to cover his shift.

Later, as Hirayama goes to his usual restaurant, he opens the door and sees the proprietor embracing a man (Min Tanaka).

Hirayama hurries off, buying cigarettes and three canned highballs to consume at a nearby riverbank.

The man Hirayama saw at the restaurant approaches and asks him for a cigarette.

The man tells him the restaurant proprietor is his ex-wife whom he had not seen in seven years and that she opened her restaurant the year after divorcing him.

He says he visited her to make peace before he dies from cancer, telling Hirayama to look after her.

Hirayma lightens the mood by offering him a drink and inviting him to play shadow tag, and they eventually part ways.

The following morning, Hirayama begins another workweek.

As he drives his van and listens to Nina Simone sing “Feeling Good“, a range of powerful emotions washes over his face.

Above: American musician / activist Nina Simone (née Eunice Kathleen Waymon) (1933 – 2003)

Realistically, for many men, the trick is finding the heart in the work you already do.

It is possible to be an honest real estate salesman, lawyer, politician, doctor, and so on.

Think about your job.

How would you go about removing the facade that is traditionally built up in your line of work so that you can be more of the real you?

An architect gives up on the entire concept of deadlines, realizing that the word itself is sinister.

He tells his clients in advance that he uses “alive-lines” – realistic but flexible schedules that can be negotiated as they proceed – and the result will be a better building.

A bank manager places before all other priorities the considerate development of his staff’s careers.

A shop assistant, a young man 20-something, is so gentle and tender in his handling of a confused old lady that it brings tears to those that observe the scene.

These people are different from the norm.

They transform the banal into magic.

They have the confidence that comes from some inner sense of what matters.

We have recessions because there is no growth in the economy.

Yet we live in a finite world that cannot sustain growth anyhow.

So an economic boom is disastrous as well.

When mainstream men abandon their urge to compete and simply enjoy being and doing what is useful as opposed to profitable, then we will have the kind of stable economy the world needs.

Instead of more factories and office towers, we will build a spiritual, intellectual and social infrastructure that will make us healthy, secure and self-sufficient – qualities that even measured in Turkish liras, US dollars or EU euros will be impressive.

Love, fun and idealism have as much place at work as in any other aspect of life.

I am reminded of the Hermann Hesse classic Siddhartha:

The story takes place in ancient India and Nepal.

Siddhartha decides to leave his home in the hope of gaining spiritual illumination by becoming an ascetic wandering beggar of the Śamaṇa.

Joined by his best friend Govinda, Siddhartha fasts, becomes homeless, renounces all personal possessions, and intensely meditates, eventually seeking and personally speaking with Gautama, the famous Buddha, or Enlightened One.

Afterward, both Siddhartha and Govinda acknowledge the elegance of the Buddha’s teachings.

Although Govinda hastily joins the Buddha’s order, Siddhartha does not follow, claiming that the Buddha’s philosophy, though supremely wise, does not account for the necessarily distinct experiences of each person.

He argues that the individual seeks an absolutely unique, personal meaning that cannot be presented to him by a teacher.

He thus resolves to carry on his quest alone.

Siddhartha crosses a river and the generous ferryman, whom Siddhartha is unable to pay, merrily predicts that Siddhartha will return to the river later to compensate him in some way.

Venturing onward toward city life, Siddhartha discovers Kamala, the most beautiful woman he has yet seen.

Kamala, a courtesan, notes Siddhartha’s handsome appearance and fast wit, telling him that he must become wealthy to win her affections so that she may teach him the art of love.

Although Siddhartha despised materialistic pursuits as a Śamaṇa, he agrees now to Kamala’s suggestions.

She directs him to the employ of Kamaswami, a local businessman, and insists that he have Kamaswami treat him as an equal rather than an underling.

Siddhartha easily succeeds, providing a voice of patience and tranquility, which Siddhartha learned from his days as an ascetic, against Kamaswami’s fits of passion.

Thus Siddhartha becomes a rich man and Kamala’s lover, though in his middle years he realizes that the luxurious lifestyle he has chosen is merely a game that lacks spiritual fulfillment.

Leaving the fast-paced bustle of the city, Siddhartha returns to the river fed up with life and disillusioned, contemplating suicide before falling into a meditative sleep, and is saved only by an internal experience of the holy word, Om.

The very next morning, Siddhartha briefly reconnects with Govinda, who is passing through the area as a wandering Buddhist.

Siddhartha decides to live the rest of his life in the presence of the spiritually inspirational river.

Siddhartha thus reunites with the ferryman, named Vasudeva, with whom he begins a humbler way of life.

Although Vasudeva is a simple man, he understands and relates that the river has many voices and significant messages to divulge to any who might listen.

Some years later, Kamala, now a Buddhist convert, is travelling to see the Buddha at his deathbed, accompanied by her reluctant young son, when she is bitten by a venomous snake near Siddhartha’s river.

Siddhartha recognizes her and realizes that the boy is his own son.

After Kamala’s death, Siddhartha attempts to console and raise the furiously resistant boy, until one day the child flees altogether.

Although Siddhartha is desperate to find his runaway son, Vasudeva urges him to let the boy find his own path, much like Siddhartha did himself in his youth.

Listening to the river with Vasudeva, Siddhartha realizes that time is an illusion and that all of his feelings and experiences, even those of suffering, are part of a great and ultimately jubilant fellowship of all things connected in the cyclical unity of nature.

After Siddhartha’s moment of illumination, Vasudeva claims that his work is done and he must depart into the woods, leaving Siddhartha peacefully fulfilled and alone once more.

Towards the end of his life, Govinda hears about an enlightened ferryman and travels to Siddhartha, not initially recognizing him as his old childhood friend.

Govinda asks the now-elderly Siddhartha to relate his wisdom and Siddhartha replies that for every true statement there is an opposite one that is also true, that language and the confines of time lead people to adhere to one fixed belief that does not account for the fullness of the truth.

Because nature works in a self-sustaining cycle, every entity carries in it the potential for its opposite and so the world must always be considered complete.

Siddhartha simply urges people to identify and love the world in its completeness.

Siddhartha then requests that Govinda kiss his forehead and, when he does, Govinda experiences the visions of timelessness that Siddhartha himself saw with Vasudeva by the river.

Govinda bows to his wise friend and Siddhartha smiles radiantly, having found enlightenment.

Thus he experiences a whole circle of life.

He realizes his father’s importance and love when he himself becomes a father and his own son leaves him to explore the outside world.

Money pays the bills, but life should be more than just paying bills.

Echegaray, Hirayama and Siddhartha all had passion for what they did.

They did their share to contribute to the world in their own unique ways.

They were able to support themselves and in their individual ways improved the lives of others, enhancing their lives and futures.

They found the heart in the work they did.

Man has a thirst for knowledge.

He wants to know what the world around him looks like and how it functions.

Man thinks.

He draws conclusions from the data he collects.

Man is creative.

He makes something new out of the information acquired.

Man is sensitive.

As a result of his exceptionally wide, multidimensional emotional scale, he not only registers the commonplace in fine gradations but he creates and discovers new emotional values and makes them accessible to others through sensible descriptions or recreates them as an artist.

Man’s curiosity is universal.

There is almost nothing that does not interest him.

Men not only observe the world around them, it is in their nature to make comparisons and to apply the knowledge they have gained elsewhere with the ultimate aim to transform this newfound knowledge into something else, something new.

With his many gifts men would appear to be ideally suited, both mentally and physically, to lead a life both fulfilled and free.

If a young man gets married, starts a family and spends the rest of his life working at a soul-destroying job, he is held up as an example of virtue and responsibility.

Another type of man, living only for himself, working only for himself, doing first one thing and then another simply because he enjoys it and because he has to keep only himself, sleeping where and when he wants, and facing woman when he meets her, on equal terms and not as a servant somehow expected to serve woman simply by virtue of her sex, is rejected by society.

The free unshackled man has no place in society.

How depressing it is to see men betraying all that they were born to.

New worlds could be discovered, instead we focus on the preservation of the status quo.

Instead we forsake all our tremendous potential and permit our minds and bodies to be distracted by the need to appease the eternally-dissatisfied opposite gender.

I find myself thinking of the movie My Fair Lady.

In London, Professor Henry Higgins, a scholar of phonetics, believes that one’s accent determines a person’s prospects in society (“Why Can’t the English?“).

At the Covent Garden fruit-and-vegetable market one evening, he listens to Eliza Doolittle, a young flower seller with a strong Cockney accent, and makes notes.

This causes others to suspect he is a “tec” (detective).

When Eliza protests that she has done nothing wrong, she asks Colonel Hugh Pickering, himself a phonetics expert, to confirm this.

Pickering and Higgins are delighted to become acquainted.

In fact, Pickering had come from India just to meet Higgins.

Higgins boasts he could teach even someone like Eliza to speak so well he could pass her off as a duchess at an embassy ball.

Eliza wants to work in a flower shop, but her accent makes that impossible (“Wouldn’t It Be Loverly“).

The following morning, Eliza shows up at Higgins’s home, seeking lessons.

Pickering is intrigued and offers to cover all the attendant expenses if Higgins succeeds.

Higgins agrees and describes how women ruin lives (“I’m an Ordinary Man“).

Eliza’s father, Alfred P. Doolittle, a dustman, learns of his daughter’s new residence (“With a Little Bit of Luck“).

He shows up at Higgins’s house three days later, ostensibly to protect his daughter’s virtue, but in reality to extract some money from Higgins, and is bought off with £5.

Higgins is impressed by the man’s honesty, his natural gift for language, and especially his brazen lack of morals.

Higgins recommends Alfred to a wealthy American who is interested in morality.

Eliza endures Higgins’s demanding teaching methods and harsh treatment (“Just You Wait“), while the servants feel both annoyed with the noise as well as pity for Higgins (“Servants’ Chorus“).

She makes no progress, but just as she, Higgins, and Pickering are about to give up, Eliza finally “gets it” (“The Rain in Spain“).

She instantly begins to speak with an impeccable upper-class accent, and is overjoyed at her breakthrough (“I Could Have Danced All Night“).

As a trial run, Higgins takes her to Ascot Racecourse (“Ascot Gavotte“), where she makes a good impression initially, only to shock everyone by a sudden lapse into vulgar Cockney while cheering on a horse.

Higgins is amused.

There, she meets Freddy Eynsford-Hill, a young upper-class man who becomes infatuated with her (“On the Street Where You Live“).

Higgins then takes Eliza to an embassy ball, where she dances with a foreign prince.

Zoltan Karpathy, a Hungarian trained by Higgins, watches and listens, and declares she is a Hungarian princess.

Afterward, Eliza’s hard work is ignored, with all the praise going to Higgins (“You Did It“).

This and his callous treatment of her, especially his indifference to her future, causes her to walk out on him, but not before she throws his slippers at him, leaving him mystified by her ingratitude (“Just You Wait [Reprise]“).

Outside, Freddy is waiting (“On the Street Where You Live [Reprise]“) and greets Eliza, who is irritated by him as all he does is talk (“Show Me“).

She tries to return to her old life, but finds that she no longer fits in.

She meets her father, who has been left a large fortune by the wealthy American to whom Higgins had recommended him, and is resigned to marrying Eliza’s stepmother.

Alfred feels that Higgins has ruined him, lamenting that he is now bound by “middle-class morality” (“Get Me to the Church On Time“).

Eliza eventually visits Higgins’s mother, who is outraged at her son’s behavior.

The next day, Higgins finds Eliza gone and searches for her (“A Hymn to Him“), eventually finding her at his mother’s house.

He attempts to talk her into coming back to him.

He becomes angered when she announces that she is going to marry Freddy and become Karpathy’s assistant (“Without You“).

He goes home, predicting that she will come crawling back.

However, he comes to the realization that she has become important to him (“I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face“).

He turns on his gramophone and listens to her voice.

When she shows up, Higgins nonchalantly asks:

“Eliza, where the devil are my slippers?“

Higgins, forgive the bluntness, but if I’m to be in this business, I shall be a responsible for the girl.

Are you a man of good character where women are concerned?

Have you ever met a man of good character where women are concerned? Well, I haven’t.

I find the moment that a woman makes friends with me, she becomes jealous, exacting, suspicious and a damn nuisance.

And I find that the moment I make friends with a woman, I become selfish and tyrannical.

So here I am, a confirmed old bachelor and likely to remain so.

Well after all, Pickering:

I’m an ordinary man

Who desires nothing more

Than just an ordinary chance to live exactly as he likes

And do precisely what he wants.

An average man am I, of no eccentric whim

Who likes to live his life, free of strife

Doing whatever he thinks is best, for him.

Well, just an ordinary man

But, let a woman in your life

And your serenity is through.

She’ll redecorate your home, from the cellar to the dome

Then go on to the enthralling fun of overhauling you.

Let a woman in your life

And you’re up against a wall.

Make a plan and you will find

She has something else in mind

And so rather than do either

You do something else that neither likes at all.

You want to talk of Keats or Milton.

She only wants to talk of love.

You go to see a play or ballet

And spend it searching for her glove.

Let a woman in your life

And you invite eternal strife.

Let them buy their wedding bands

For those anxious little hands.

I’d be equally as willing for a dentist to be drilling

Than to ever let a woman in my life.

I’m a very gentle man,

Even tempered and good natured

Whom you never hear complain,

Who has the milk of human kindness

By the quart in every vein.

A patient man am I, down to my fingertips,

The sort who never could, ever would

Let an insulting remark escape his lips.

A very gentle man

But, let a woman in your life

And patience hasn’t got a chance.

She will beg you for advice, your reply will be concise

And she’ll will listen very nicely

Then go out and do precisely what she wants.

You are a man of grace and polish

Who never spoke above a hush.

Now all at once you’re using language

That would make a sailor blush.

Let a woman in your life

And you’re plunging in a knife.

Let the others of my sex

Tie the knot around their necks.

I prefer a new edition of the Spanish Inquisition

Than to ever let a woman in my life.

I’m a quiet living man

Who prefers to spend the evenings

In the silence of his room,

Who likes an atmosphere as restful

As an undiscovered tomb.

A pensive man am I, of philosophic joys

Who likes to meditate, contemplate

Free from humanity’s mad inhuman noise.

A quiet-living man

But, let a woman in your life

And your sabbatical is through.

In a line that never ends come an army of her friends

Come to jabber and to chatter

And to tell her what the matter is with you.

She’ll have a booming boisterous family

Who will descend on you en mass.

She’ll have a large Wagnerian mother

With a voice that shatters glass.

Let a woman in your life

Let a woman in your life

I shall never let a woman in my life.

I am not suggesting that we all become MGTOW (men going their own way).

I will only remark that a woman is like a road in the rain where caution is advised when encountering dangerous curves.

I tell my younger charges to build themselves up first, physically, psychologically and financially, before yearning after women.

I have no doubt with the confidence a man carries when he is physically, psychologically and financially strong he need not chase women, they will find him.

Guys (and gals), find work deserving of your time and passion.

Do what you love.

Love what you do.

Whether you are a flower girl or a ferryman, a mathematician or a bus driver, a teacher or a toilet cleaner, be professional.

Put your passion into being the best you can be, where you are, right now.

Refuse to accept those who will not love you for who you are and reject you for what you do.

Where you are does not necessarily mean that is where you must remain.

It is not the job that gives dignity to the man.

It is the man that gives dignity to the job.

Somehow, the world has become topsy-turvy.

The focus has been a woman can simply be – though they dare not be without their masks of femininity -and a man must become.

So often I hear of the impossible standards a woman insists a man must meet to be worthy of her and men reeling from rejection never realizing that it is men who are the true prize and that a woman needs to show him that they are worthy, not because they are women but in spite of this.

Let us be together not because we need one another, but because we simply want to be with one another.

Let us have an attitude of take-it-or-leave-it.

Rather than searching for happiness in a relationship, we should instead focus on making ourselves happy first.

Happiness is never found in the arms of another.

It is cultivated within ourselves and then shared with others.

Neither gender was meant to serve the other.

The Lord God said:

“It is not good for the man to be alone.

I will make a helper suitable for him.”

(Holy Bible, Genesis 2:18)

We are meant to help one another.

Talk a walk

We can hardly breathe the air

Look around

It’s a hard life everywhere

People talk but they never really care

On the street there’s a feeling of despair

Everyday, there’s a brand new baby born

Everyday, there’s a sun to keep you warm

When it’s alright

Yeah, it’s alright

I’m alive

And I don’t care much for words of doom

If it’s love you need

Well, I got the room

It’s a simple thing changed in me

When I found you

I’m alive

I’m alive

Every night on the streets of Hollywood

Pretty girls come to give you something good

Love for sale

It’s a lonely town at night

Therapy for a heart misunderstood

Look around, there’s a flower on every street

Look around and it’s growing at your feet

Everyday you can hear me say

That I’m alive

I want to take all that life has got to give

All I need is someone to share it with

I got love and love is all I really need to live

I’m alive

I’m alive

Everyday, there’s a brand new baby born

Everyday, there’s enough to keep you warm

It’s ok

And I’m glad to say

I’m alive

And I don’t care much for words of doom

If it’s love you got, well, I’ve got the room

It’s a simple thing that came to me when I found you

I’m alive

I’m alive

And I don’t care much for words of doom

If it’s love you need, well, I got the room

It’s a simple thing that came to me and I thank God

I’m alive

I can take all that life has got to give

If I’ve got someone to share it with

(“I’m Alive“, Neil Diamond)

Sources

Steve Biddulph, Manhood

Bowser and Blue, “The Colo-rectal Surgeon Song”

Lee Child, One Shot

Neil Diamond, “I’m Alive“

Flight of the Conchords, “Bus Driver“

Ronald Gross, The Independent Scholar’s Handbook

Merle Haggard, “Workin’ Man Blues“

Hermann Hesse, Siddhartha

Billy Joel, “Piano Man“

Anthea McTerrnan, “In Praise of Men“, Irish Times, 29 September 2016

My Fair Lady, “I’m an Ordinary Man“

George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four

Pink Floyd, “Comfortably Numb“

Rush, “Workin’ Man“

Tom Schulman, Dead Poets Society

George Thorogood, “Get a Haircut“

Esther Vilar, The Manipulated Man