Landschlacht, Switzerland, 30 January 2019

This is not India, but nonetheless there are a few sacred cows in Switzerland one would be wise to not offend.

First, one should never question Switzerland’s superiority….

In anything.

Just as the laws of physics decree that the bumblebee cannot possibly fly, so the laws of economics similarly decree that Switzerland should not be doing so sickeningly well.

It is land-locked, has a home market smaller than London, speaks four languages, has no natural resources other than hydroelectric power, a little salt and few fish, no colonies nor membership in any major trading block, Switzerland should have faded from existence centuries ago.

Instead the Swiss are the only nation to make the Germans appear inefficient, the French undiplomatic and Texans poor.

Thus their mountains are higher, their tunnels longer, their watches superior, their cheese holey, their chocolate legendary and their gold real.

Second, appearances are deceiving.

Switzerland is not really a nation but rather a collection of 26 nations (or cantons) which finance themselves, raise their own taxes and spend them as they want.

Or one could also easily argue that it is not a collection of 26 cantons but rather an assemblage of 3,000 totally independent communities each making their own decisions about welfare, gas, electricity, water, roads and public holidays.

They are successful and proud of what they have accomplished yet simultaneously refuse to believe they are doing well and are convinced that tomorrow they will lose everything they have worked for.

They are officially quadlingual polyglots.

Yet not only have I never heard of anyone who can speak all four (French, German, Italian and Rumanisch) languages, I have rarely encountered outside of Freiburg/Freibourg and Biel/Bienne anyone who is bilingual in even two of the four.

In the Bundeshaus in Bern (the national/federal parliament in the capital) one sees a minor miracle of one member speaking in one language while the other member responds in a different one with no loss of comprehension or pause in conversation.

But beyond Bern, when the Swiss have to communicate in an official language not their own, then in all likelihood the French speaker will address his German counterpart in English and vice versa.

The Swiss Army doesn’t actually use the Swiss Army knives the tourists buy.

Swiss cheese is not called Swiss but Emmentaler.

Swiss fondue is simply (cheese) fondue while a meat fondue is inexplicably called a Chinese fondue.

Two Swiss national heroes are also problematic puzzlers.

Heidi, everyone’s favourite Swiss Miss, though created by a Swiss writer, was actually a German girl who moved to Switzerland to live with her Swiss grandfather in Frau Johanna Spyri’s books.

William Tell (or Wilhelm) is a proud Swiss symbol of independence but whether he actually existed or whether he was invented by those who were not Swiss (Germans Goethe and Friedrich Schiller / Italy’s Rossini) is debatable.

The cuckoo clock is not Swiss.

It is German from the Black Forest, despite what Orson Wells would have us believe.

Trains are not as punctual as the legend suggests that folks could use their stopwatches to predict a train’s exact arrival.

The S8 connecting Schaffhausen with St. Gallen is, in my personal experience of using it on an almost daily basis, more often tardy rather than timely.

The Swiss are world class diploments who make the world believe that they want the world to love them, but they have a problem with not loving the world in return but not liking other Swiss as well.

They are famous for their neutrality yet armed to the teeth.

And much like my fellow Canadians, they are proud of their homeland yet would be hard-pressed to say what exactly that identity is of which they are proud.

They are conservative to the extreme, yet Switzerland has harboured radicals of every political ideology imaginable (including Mussolini and Lenin), has surprised with artistic movements (like Dadaism and Bauhaus) and has sheltered movie and music legends who revolutionized the world with their creativity and talent (like Freddy Mercury, Charlie Chaplin and Tina Turner).

Switzerland is dull and uninspiring.

Even though Mary Shelley was English her Frankenstein‘s Monster was as Swiss as the Matterhorn.

James Bond is the product of a Swiss mother and a Scottish father and much of Bond lore (movies and literature) has taken place within Switzerland.

A land of contradictions with an identity as firmly guarded as a bank vault.

Let us consider Swiss chocolate.

The world over, chocolate is the foodstuff most readily identifiable with Switzerland.

Chocolate is everywhere.

It is the afternoon pick-me-up, the sensual indulgence, the accoutrement to seduction.

The ancient Aztecs believed that chocolate was an aphrodisiac and Emperor Montezuma would gorge himself on chocolate in advance of his trysts as a type of non-prescription Viagra.

The solid, moldable chocolate “bar” was developed by the Bristol confectioner Joseph Fry in 1847.

But many early pioneers of chocolate-making were Swis:

- Francois-Louis Cailler, who started production of what was then largely sold as a restorative tonic at Vevey in 1819.

- He was soon followed by Philippe Suchard in Neuchâtel.

- Until 1875, all chocolate was dark and bitter, but in that year Vevey-based Daniel Peter, a candlemaker who married Cailler’s daughter, became involved in chocolate-making, invented milk chocolate, aided by his neighbour Henri Nestlé.

- Nestlé started his firm (now one of the world’s largest food multinationals) by manufacturing condensed milk, which Peter used in chocolate manufacture in preference to the too-watery ordinary milk, creating a concoction that was not only more palatable than previously available but less expensive as well.

- In 1879 Rodolphe Lindt of Bern invented “conching“, a process which creates the smooth melting chocolate familiar today.

- Jean Tobler, also of Bern, was another pioneer and today every one of the seven billion triangles of Toblerone eaten annually are still produced in that city.

Today, more chocolate is sold in Switzerland per head of population than any other country.

The seeds of the cacao tree have an intense bitter taste and must be fermented to develop the flavor.

After fermentation, the beans are dried, cleaned, and roasted.

The shell is removed to produce cacao nibs, which are then ground to cocoa mass, unadulterated chocolate in rough form.

Once the cocoa mass is liquefied by heating, it is called chocolate liquor.

The liquor also may be cooled and processed into its two components: cocoa solids and cocoa butter.

Baking chocolate, also called bitter chocolate, contains cocoa solids and cocoa butter in varying proportions, without any added sugar.

Powdered baking cocoa, which contains more fiber than it contains cocoa butter, can be processed with alkali to produce Dutch cocoa.

Much of the chocolate consumed today is in the form of sweet chocolate, a combination of cocoa solids, cocoa butter or added vegetable oils, and sugar.

Milk chocolate is sweet chocolate that additionally contains milk powder or condensed milk.

White chocolate contains cocoa butter, sugar, and milk, but no cocoa solids.

Chocolate is one of the most popular food types and flavors in the world, and many foodstuffs involving chocolate exist, particularly desserts, including cakes, pudding, mousse, chocolate brownies, and chocolate chip cookies.

Many candies are filled with or coated with sweetened chocolate, and bars of solid chocolate and candy bars coated in chocolate are eaten as snacks.

Gifts of chocolate molded into different shapes (such as eggs, hearts, coins) are traditional on certain Western holidays, including Christmas, Easter, Valentine’s Day and Hanukkah.

Chocolate is also used in cold and hot beverages, such as chocolate milk and hot chocolate, and in some alcoholic drinks, such as creme de cacao.

Chocolate is big business.

In 2005 the global market was approximately $100 billion.

Each year, the world consumes close to three million tons of chocolate and other cocoa products.

One Swiss firm alone, Lindt & Sprüngli had a revenue of CHF 4.088 billion in 2017.

It was my discovery that Lindt has their headquarters and outlet shop in Kilchberg (near Zürich) and a separate visit to Maestrani’s Chocolarium outside the town of Flawil (near St. Gallen) that made me curious about the actual production of chocolate….

Bern, Switzerland, 12 March 2013:

Lindt produces the Gold Bunny, a hollow milk chocolate rabbit in a variety of sizes available every Easter since 1952.

Each bunny wears a small coloured ribbon bow around its neck identifying the type of chocolate contained within.

The milk chocolate bunny wears a red ribbon, the dark chocolate bunny wears a dark brown ribbon, the hazelnut bunny wears a green ribbon, and the white chocolate bunny wears a white ribbon.

Other chocolates are wrapped to look like carrots, chicks, or lambs.

The lambs are packaged with four white lambs and one black lamb.

During the Christmas season, Lindt produces a variety of items, including chocolate reindeer (which somewhat resemble the classic bunny), Santa, snowmen figures of various sizes, bears, bells, advent calendars and chocolate ornaments.

Various tins and boxes are available in the Lindt stores, the most popular colour schemes being the red and blue.

Other seasonal items include Lindt chocolate novelty golf balls.

For Valentine’s Day, Lindt sells a boxed version of the Gold Bunny, which comes as a set of two kissing bunnies.

Other Valentine’s Day seasonal items include a selection of heart-shaped boxes of Lindor chocolate truffles.

They are the symbol of Easter in Switzerland, but the golden Lindt bunnies aren’t Swiss.

As revelations go, this one is up there with Heidi was German and Switzerland isn’t neutral in terms of shock value.

How can those cute little gold-wrapped bunnies not be Swiss?

They are made by Lindt & Sprüngli, one of the oldest and most famous chocolate makers in Switzerland.

Except they are made by Lindt & Sprüngli in Germany.

Diccon Bewes discovered this thanks to a friend from Helvetica LA who bought a Lindt bunny in Los Angeles only to find it was made in Germany.

Fair enough, Bewes thought, as America is an export market.

But surely the ones in Switzerland would be made here?

Wrong.

All the ones in the supermarkets in Bern are made in Germany, although you have to have good eyesight to discover that.

On the back of the bunny the ingredients are listed in German, French and Dutch but down at the bottom are the words:

Fabriqué par / Geproduceerd door: Lindt & Sprüngli GmbH (Allemagne/Deutschland) D-52072 Aachen.

Oddly this isn’t written in German given that they are sold in Germany.

Obviously they don’t want to have that anywhere for fear of scaring away canny Swiss consumers – even though most of them can understand the French anyway!

To reassure anyone who does cotton on to the fact that the bunny isn’t Swiss, there are the words:

Garantie de Qualité Chocoladefabriken Lindt & Sprüngli Kilchberg/Suisse.

In other words, Lindt in Switzerland is the distributor for the German Lindt products.

At a time when “Swissness” is being debated in the Federal Parliament, it is interesting to see that this Swiss icon is not Swiss at all.

Bewes checked the shelves and Lindt very carefully marks their chocolate bars with SWISS MADE where it applies (so the bunny does not get that stamp of approval).

There was a proposal that foodstuffs get the SWISS MADE stamp only if 80% of their ingredients are Swiss, unless they include things that cannot possibly be Swiss because they are not grown here….

Landschlacht, Switzerland, 29 January 2019

But here’s the thing.

Not only is much of Swiss chocolate production reliant on imported sugar, but cocoa, the raw material of chocolate, itself isn’t grown in Switzerland.

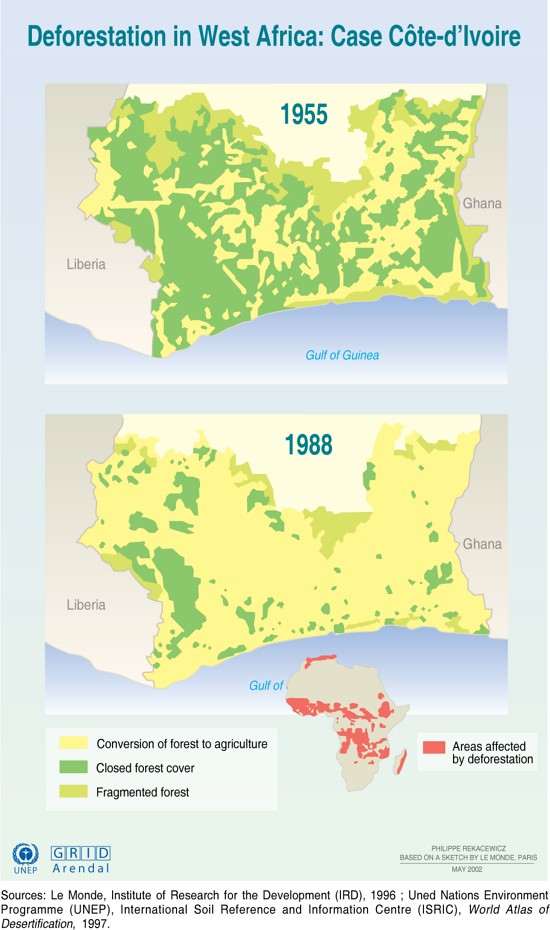

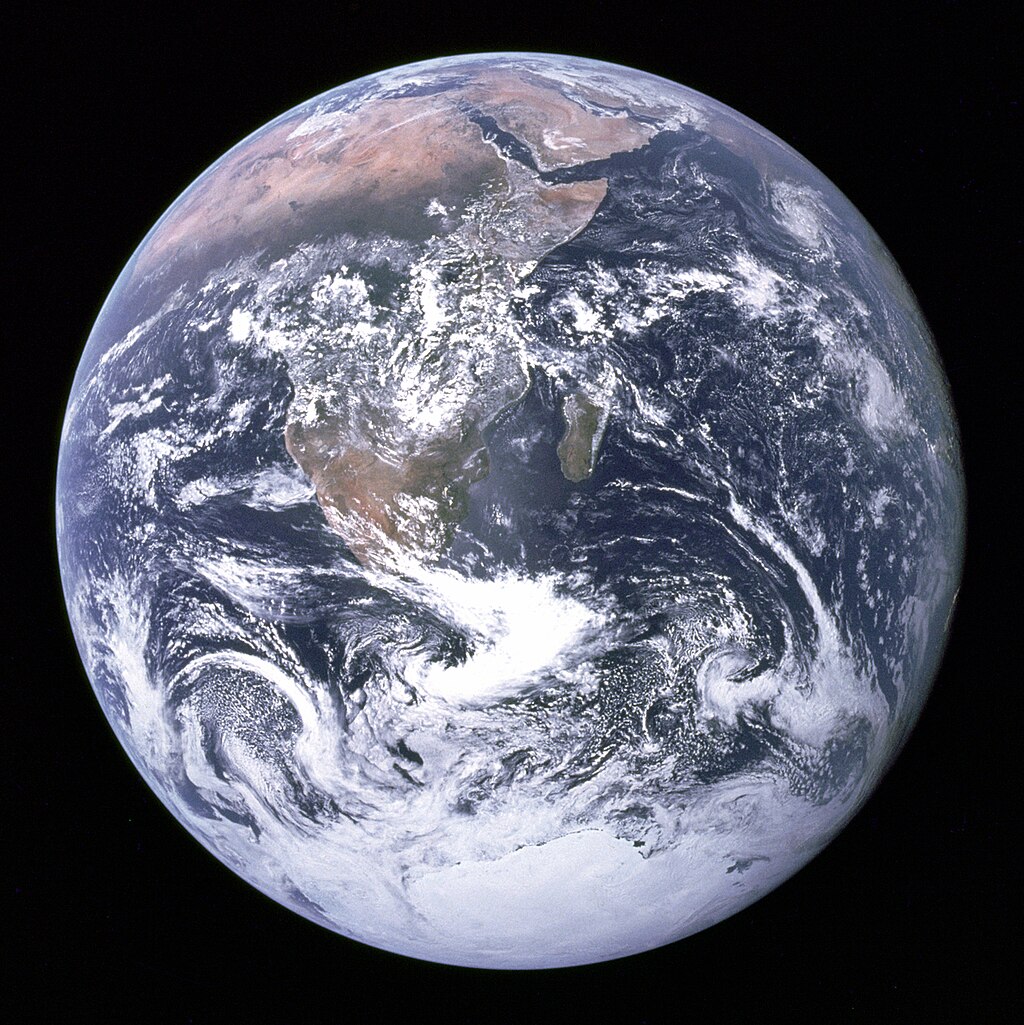

Although cocoa originated in the Americas, West African countries, particularly Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, are the leading producers of cocoa in the 21st century, accounting for some 60% of the world cocoa supply.

Thousands of miles away from the American and European homes, where the majority of the world’s chocolate is devoured – Europe accounts for 45% of the world’s chocolate revenue – lies the denuded landscape of West Africa’s Côte d’Ivoire, the world’s largest producer of cocoa.

As the nation’s name suggests, elephants once abundantly roamed the rain forests of the Côte d’Ivoire.

Today’s reality is much different.

Only 200 – 400 elephants remain from an original population of hundreds of thousands.

Much of the country’s national parks and conservation lands have been cleared of their forests to make way for cocoa operators to feed demand from large chocolate companies like Nestlé, Cadbury and Mars.

Washington DC, 15 September 2017

NGO Mighty Earth released the results of an in-depth global investigation into the cocoa cartel that produces the raw material for chocolate.

The chocolate companies purchase the cocoa for their chocolate production from large agribusiness companies like Olam, Cargill and Barry Callebaut, who together control half the monopoly of global cocoa trade.

Most strikingly, the investigation found that for years the world’s major chocolate companies have been buying cocoa grown through the illegal deforestation of national parks and other protected forests, in addition to driving extensive deforestation outside of protected areas.

In the world’s two largest cocoa producing countries, Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, the market created by the chocolate industry has been the primary driver behind the destruction of forests.

Much of Côte d’Ivoire’s national parks and protected areas have been entirely or almost entirely cleared of forest and replaced with cocoa growing operations.

In the developed world, chocolate is seen as an affordable luxury that gives ordinary people a taste of sensuous delight at a modest cost.

But in West Africa, chocolate is rare and unaffordable to the majority of the population.

Most Ivorian cocoa farmers have never even tried chocolate.

Much of Côte d’Ivoire was densely covered by forests when it achieved independence in 1960, making it prime habitat for forest elephants and chimpanzees.

Elephants are on the verge of total disappearance.

13 of 23 Ivorian protected areas have lost their entire primate populations.

Chimpanzees are now considered an endangered species.

Côte d’Ivoire once boasted one of the highest rates of biodiversity in Africa, with thousands of endemic species.

Pygmy hippos, flying squirrels, pangolins, leopards and crocodiles are rapidly losing their last habitats.

Today less than 12% of the country remains forested and less than 4% remains densely forested.

The cocoa industry in Côte d’Ivoire has not been content with landscapes it was able to clear legally.

In recent years, it has pushed large-scale growing operations into the country’s national parks and other protected areas.

Needless to say, clearing forest to produce cocoa within protected areas violates Ivorian law.

Above: Flag of Côte d’Ivoire

A study conducted by Ohio State University and several Ivorian academic institutions examined 23 protected areas in Côte d’Ivoire and found that seven of them had been entirely converted to cocoa.

More than 90% of the land mass of these protected areas was estimated to be covered by cocoa.

Mighty Earth investigated Goin Débé Forest, Scio Forest, Mt. Péko National Park, Mt. Sassandra Forest, Tia Forest and Marahoué National Park.

Three of the world’s largest cocoa traders – Olam, Cargill and Barry Callebaut – buy cocoa grown illegally in protected areas.

They sell this cocoa to the world’s largest chocolate companies like Mars, Hershey, Mondelez, Ferrero, Lindt and others.

Other traders engage in similar practices.

Illegal deforestation for cocoa is an open secret throughout the entire chocolate supply chain.

Between five and six million people, largely small landholders, grow cocoa around the world.

In Côte d’Ivoire, cocoa farmers, who produce 43% of the world’s cocoa, earn around US 50 cents per day, 6.6% of the value of a chocolate bar.

By comparison, 35% goes to chocolate companies and 44% goes to retailers.

Additionally, the chocolate industry is notorious for labour rights abuses including slave labour and child labour.

According to the US Department of Labor:

“21% more children are illegally laboring on cocoa farms in Ghana and the Ivory Coast than five years ago.”

An estimated 2.1 million West African children are still engaged in dangerous, physically taxing cocoa harvesting.

Rather than eliminate the problem, the industry has merely pledged to reduce child labour in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana by 70% by 2020.

The investigation implicates almost every major chocolate brand and retailer, including Lindt & Sprüngli and my employer Starbucks.

Mighty Earth shared the findings with 70 chocolate companies.

None denied sourcing cocoa from protected areas.

None disputed any of the facts presented.

Kilchberg, Switzerland, 12 August 2018

This bedroom community of Zürich has only 8,470 people, but it is a significant place for three reasons:

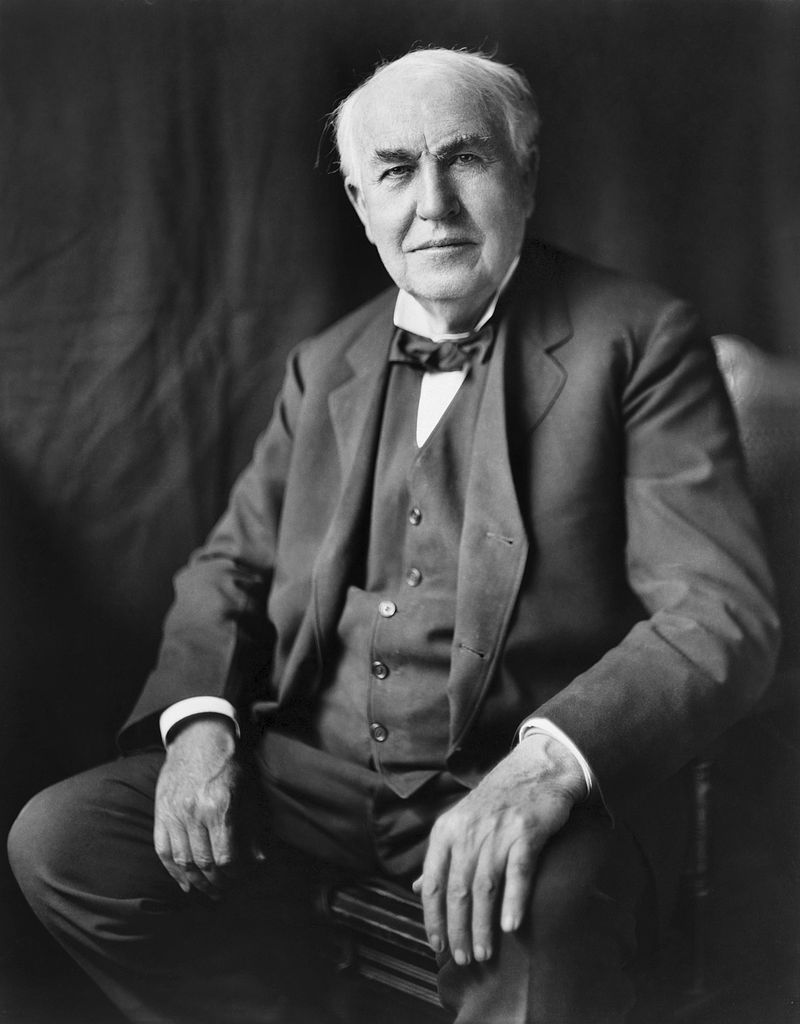

- It was the final home and resting place for Nobel Prize German author Thomas Mann as well as his wife and most of his children.

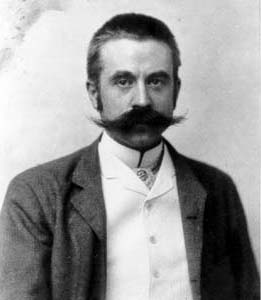

Above: Thomas Mann (1875 – 1955)

(See Canada Slim and the Family of Mann of this blog.)

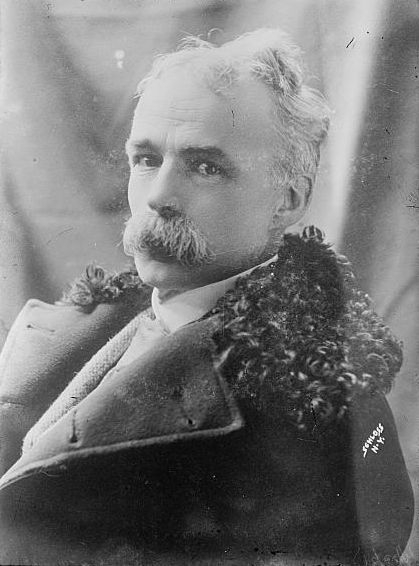

- It was also the final home and resting place of Swiss author Conrad Ferdinand Meyer, in whose honour Kilchberg has a Museum.

Above: Conrad Meyer (1825 – 1898)

(See Canada Slim and the Anachronistic Man of this blog.)

- It was the final home and resting place of Swiss chocolatier David Sprüngli-Schwartz and his son Rudolf Sprüngli-Ammann, and it remains the headquarters location of the company they founded, today’s Lindt & Sprüngli.

In 1836 David and Rudolf bought a small confectionery in the old town of Zürich, producing chocolates under the name David Sprüngli & Son.

Two years later, a small factory was added that produced chocolate in solid form.

With the retirement of Rudolf in 1892, the business was divided between his two sons.

The younger brother David received two confectionery stores that became known under the name Confiserie Sprüngli.

The elder brother Johann received the chocolate factory.

To raise the necessary finances for his expansion plans, Johann converted his private company into publicly traded Chocolat Sprüngli AG in 1899.

That same year, Johann acquired the chocolate factory of Rodolphe Lindt in Bern and the company changed its name to Aktiengesellschaft (AG) Vereingte Berner und Züricher Chocoladefabriken Lindt & Sprüngli (the United Bern and Zürich Lindt and Sprüngli Chocolate Factories Ltd.).

In 1994, Lindt & Sprüngli acquired the Austrian chocolatier Hofbauer Österreich and integrated it, along with its Küfferle brand, into the company.

In 1997 and 1998, respectively, the company acquired the Italian chocolatier Caffarel and the American chocolatier Ghirardelli, and integrated both of them into the company as wholly owned subsidiaries.

Since then, Lindt & Sprüngli has expanded the once-regional Ghirardelli to the international market.

On 17 March 2009, Lindt announced the closure of 50 of its 80 retail boutiques in the United States because of weaker demand in the wake of the late-2000s recession.

On 14 July 2014, Lindt bought Russell Stover Candies, maker of Whitman’s Chocolate, for about $1 billion, the company’s largest acquisition to date.

In November 2018, Lindt opened its first American travel retail store in JFK Airport’s Terminal 1 and its flagship Canadian shop in Yorkdale Shopping Centre, Toronto.

Above: Lindt Yorkdale

Lindt & Sprüngli has twelve factories: Kilchberg, Switzerland; Aachen, Germany; Oloron-Sainte-Marie, France; Induno Olona, Italy; Gloggnitz, Austria; and Stratham, New Hampshire, in the United States.

The factory in Gloggnitz, Austria, manufactures products under the Hofbauer & Küfferle brand in addition to the Lindt brand.

Caffarel’s factory is located in Luserna San Giovanni, Italy, and Ghirardelli’s factory is located in San Leandro, California, in the United States.

Furthermore, there are four more factories of Russell Stover in the United States.

Lindt has opened over 410 chocolate cafés and shops all over the world.

The cafés’ menu offers mostly focuses on chocolate and desserts.

They also sell handmade chocolates, macaroons, cakes, and ice cream.

Above: “The Little Wash House“, Lindt Café, Zürich

Originally, Lindor was introduced as a bar in 1949 and later in 1967 in form of a ball.

Lindor is a type of chocolate produced by Lindt, which is now characterized by a hard chocolate shell and a smooth chocolate filling.

It comes in both a ball and a bar variety, as well as in a variety of flavours.

Each flavour has its own wrapper colour.

Most of the US Lindor truffles are manufactured in Stratham, New Hampshire.

Lindt sells at least 29 varieties of chocolate bars.

Lindt’s “Petits Desserts” range embodies famous European desserts in a small cube of chocolate.

Flavours include: Tarte au Chocolat, Crème Brulée, Tiramisu, Creme Caramel, Tarte Citron, Meringue, and Noir Orange.

Lindt makes a “Creation” range of chocolate-filled cubes: Milk Mousse, Dark Milk Mousse, White Milk Mousse, Chocolate Mousse, Orange Mousse, Pistachio and Cherry/Chili.

Bâtons Kirsch are Lindt Kirsch liqueur-filled, chocolate-enclosed tubes dusted in cocoa powder.

In Australia, Lindt manufactures ice cream in various flavours:

- 70% Dark Chocolate

- White Chocolate Framboise

- Sable Cookies and Cream

- Chocolate Chip Hazelnut

- White Chocolate and Vanilla Bean

The curious visitor and chocolate lover can have a guided tour of the Lindt production facilities by contacting Zürich Tourism in the Zürich Main Station.

Tours take place from May to September, Monday to Saturday and last 40 minutes for individuals or groups up to 16 people.

(http://www.lindt-experience.ch)

The factory outlet shop outside the factory is open from Monday to Friday 1000 – 1900, and Saturday 1000 – 1700.

The shop is seductive, the chocolate sinful.

In 2009, Swiss tennis star Roger Federer was named as Lindt’s “global brand ambassador” and began appearing in a series of commercials endorsing Lindor.

Roger Federer has huge popularity in the world of sport, to the point that he has been called a living legend in his own time.

Given his achievements, many players and analysts have considered Federer to be the greatest tennis player of all time.

No other male tennis player has won 20 major singles titles in the Open Era and he has been in 30 major finals, including 10 in a row.

He has held the world No. 1 spot in the ATP rankings for longer than any other male player.

He was also ranked No. 1 at the age of 36.

Federer has won a record eight Wimbledon titles and a joint-record six Australian Open titles.

He also won five consecutive US Open titles, which is the best in the Open Era.

He has been voted by his peers to receive the tour Sportsmanship Award a record thirteen times and voted by tennis fans to receive the ATP Fans’ Favorite award for fifteen consecutive years.

Federer has been named the Swiss Sports Personality of the Year a record seven times.

He has been named the ATP Player of the Year and ITF World Champion five times and he has won the Laureus World Sportsman of the Year award a record five times, including four consecutive awards from 2005 to 2008.

He is also the only individual to have won the BBC Overseas Sports Personality of the Year award four times.

Federer helped to lead a revival in tennis known by many as the Golden Age.

This led to increased interest in the sport, which in turn led to higher revenues for many venues across tennis.

During this period rising revenues led to exploding prize money.

When Federer first won the Australian Open in 2004 he earned $985,000, compared to when he won in 2018 and the prize had increased to AUD 4 million.

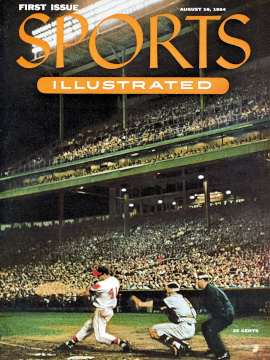

Upon winning the 2009 French Open and completing the career Grand Slam, Federer became the first individual male tennis player to grace the cover of Sports Illustrated since Andre Agassi in 1999.

He was also the first non-American player to appear on the cover of the magazine since Stefan Edberg in 1992.

Federer again made the cover of Sports Illustrated following his record breaking 8th Wimbledon title and second Grand Slam of 2017, becoming the first male tennis player to be featured on the cover since himself in 2009.

Federer is one of the highest-earning athletes in the world.

He is listed at No. 1 on the Forbes “World’s Highest Paid Athletes” list.

He is endorsed by Japanese clothing company Uniqlo and Swiss companies Nationale Suisse, Credit Suisse, Rolex, Lindt, Sunrise, and Jura Elektroapparate.

In 2010, his endorsement by Mercedes-Benz China was extended into a global partnership deal.

His other sponsors include Gillette, Wilson, Barilla, and Moët & Chandon.

Previously, he was an ambassador for Nike, NetJets, Emmi AG and Maurice Lacroix.

In 2003, he established the Roger Federer Foundation to help disadvantaged children and to promote their access to education and sports.

Since May 2004, citing his close ties with South Africa, including that this was where his mother had been raised, he began supporting the South Africa-Swiss charity IMBEWU, which helps children better connect to sports as well as social and health awareness.

Later, in 2005, Federer visited South Africa to meet the children that had benefited from his support.

Also in 2005, he auctioned his racquet from his US Open championship to aid victims of Hurricane Katrina.

At the 2005 Pacific Life Open in Indian Wells, Federer arranged an exhibition involving several top players from the ATP and WTA tour called Rally for Relief.

The proceeds went to the victims of the tsunami caused by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake.

In December 2006, he visited Tamil Nadu, one of the areas in India most affected by the tsunami.

He was appointed a Goodwill Ambassador by UNICEF in April 2006 and has appeared in UNICEF public messages to raise public awareness of AIDS.

In response to the 2010 Haiti earthquake, Federer arranged a collaboration with fellow top tennis players for a special charity event during the 2010 Australian Open called ‘Hit for Haiti‘, in which proceeds went to Haiti earthquake victims.

He participated in a follow-up charity exhibition during the 2010 Indian Wells Masters, which raised $1 million.

The Nadal vs. Federer “Match for Africa” in 2010 in Zürich and Madrid raised more than $4 million for the Roger Federer Foundation and Fundación Rafa Nadal.

In January 2011, Federer took part in an exhibition, Rally for Relief, to raise money for the victims of the Queensland floods.

In 2014, the “Match for Africa 2” between Federer and Stan Wawrinka, again in Zurich, raised £850,000 for education projects in Southern Africa.

On 24 November 2017, Federer received an honorary doctorate awarded to him by his home university, the University of Basel.

He received the title in recognition for his role in increasing the international reputation of Basel and Switzerland and also his engagement for children in Africa through his charitable foundation.

But is he aware of the damage that Lindt’s demand for cocoa is doing to West Africa in regards to the destruction of both human lives and the environment?

Or, if he is aware, is he like many things Swiss – deceptive in appearance?

Flawil, Switzerland, 16 January 2018

As you pull into St. Gallen train station, you can’t miss the huge Chocolat Maestrani sign suspended above the tracks.

The local firm in nearby Flawil and the chocolate factory is within easy reach west of St. Gallen.

The name Maestrani has stood for exquisite chocolate creations since 1852.

At Maestrani’s Chocolarium – the Chocolate Factory of Happiness – the history of chocolate is brought alive in a fascinating Experience World for young and old alike.

Whether independently or on a guided tour, guests can explore the interactive zone and discover where chocolate comes from and how it is produced.

They also have the chance to view chocolate being produced live.

What’s more, sampling is actively encouraged!

At the end of the tour, for a small surcharge, a show confiseur will mold a fresh bar of chocolate, which guests can decorate as they wish.

Besides a movie theater, a cafe and chocolate molding courses, during which guests can make their own chocolate creations, sweet-toothed visitors can purchase their favorite chocolate products from the factory shop.

“He who sees the world through the eyes of a chocolate lover will find true beauty and happiness.” Aquilino Maestrani, founder and chocolate pioneer, (1814-1880)

The Chocolarium at Toggenburgerstrasse 41, Flawil, is open Monday to Friday 0900 – 1800, Saturday 0900 – 1700, Sunday 1000 – 1700, the last tour is one hour before closing.

The tour includes a gallery above the factory floor to watch the production lines.

To get there, take a train to Flawil from St. Gallen (12 minutes) then switch to a bus for the five-minute ride to “Flawil Maestrani” bus stop.

Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa, 30 January 2019

It is a stunner, shingled with starfish-studded sands, palm tree forests and roads so orange they resemble strips of bronzing powder.

This is a true tropical paradise.

Above: Azuretti Beach, Grand Bassam, Côte d’Ivoire

In the south, the Parc National de Tai hides secrets, species and nut-cracking chimps under the tree boughs.

Above: Parc National de Tai, Côte d’Ivoire

The peaks and valleys of Man offer a highland climate, fresh air and fantastic hiking opportunities through tropical forests.

Above: Dent de Man, Côte d’Ivoire

The beach resorts of Assinie and Grand Bassam are made for weekend retreats from Abidjan, capital in all but name, where lagoons wind their way between skyscrapers and cathedral spires pierce the heavens.

Above: Images of Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

Assinie and Dagbego have surf beaches.

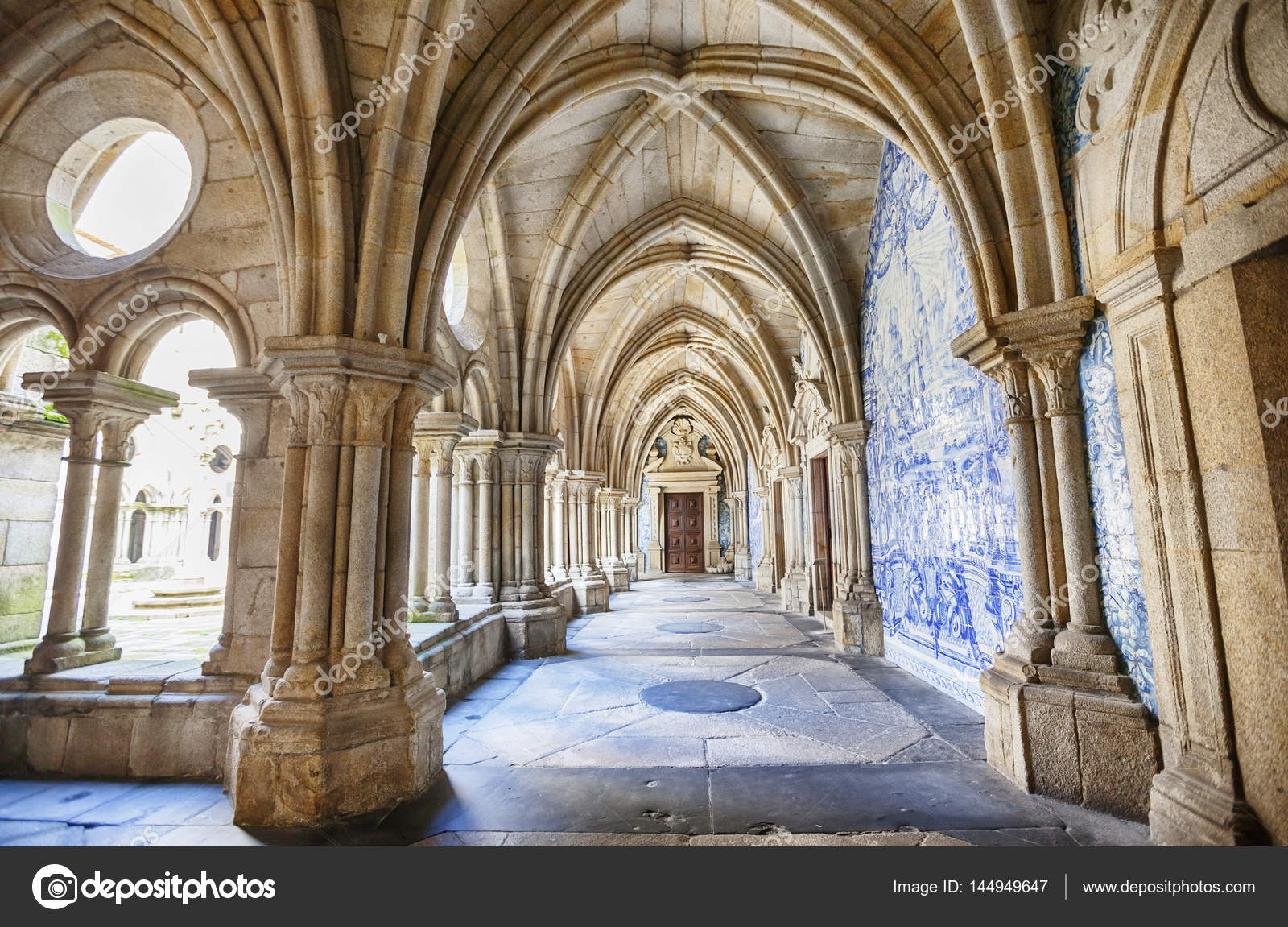

In Yamoussoukro, the capital’s basilica floats on the landscape like a mirage.

Above: Basilica of Our Lady of Peace, Yamoussoukro, Côte d’Ivoire

Sacred crocodiles guard the Presidential Palace.

Tourists gather as they are fed in the afternoon.

Above: Lac aux Crocodiles, Presidential Palace, Yamoussoukro

This is a culture rich with festivals and some of the most stunning artwork in Africa.

This is what the tourist sees.

The process of deforestation starts with settlers who invade parks and other forested areas.

They progressively cut down or burn existing trees.

Trunks are denuded of their crowns and are left as ghostly reminders of the great forests that once reigned.

With the forests gone, the settlers plant cocoa trees, which take years before they are ready to harvest.

Each cocoa tree bears two harvests of cocoa pods per year.

Farmers hack off the ripe cocoa pods from the trees with machetes.

They split open the pods to remove the cocoa beans, which are sorted and placed into piles.

The beans are left in the sun to ferment and dry and turn brown.

It is at this point that a first level of middlemen called “pisteurs” buy the cocoa beans from the settlers, transport it to villages and towns across the cocoa-growing region and sell them onto another set of middlemen, known as cooperatives.

The cooperatives then either directly or through a third set of middlemen bring the cocoa to the coastal ports of San Pedro and Abidjan, where it is sold to cocoa traders Olam, Cargill and Barry Callebaut, who ship the cocoa companies in Europe and North America.

Illegal towns and villages called “campements” have sprung up inside Côte d’Ivoire’s national parks and protected forests.

Some campements boast tens of thousands of residents, along with public schools, official health centres, mosques, churches, stores and cell phone towers in plain sight of government authorities.

There is an excessive use of fertilizers and pesticides that is killing the country’s biodiversity.

Deforestation and exposure to the fullness of the sun makes the environment suspectible to disease.

Over two million children are victims of the worst forms of child labour.

This is a land of child workers, slaves and low wages.

Low pay foments food insecurity and low school enrollment and attendance rates.

Inadequate prices paid for the coffee means farmers live under the poverty line.

Chemicals pollute the waterways, killing wildlife and harming communities.

This is a true tropical hell.

And what of the future?

Demand for chocolate continues to rise by 5% every year.

The chocolate industry has aggressively expanded to other rainforest nations around the world – Indonesia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Peru – exporting the same bad practices that are contributing to the destruction of West Africa’s forests and the creation of a living hell for its people.

Deforestation for cocoa has a significant impact on climate.

Tropical rainforests have among the highest carbon storage of any ecosystem on the planet.

When they are cleared, they release enormous amounts of carbon into the atmosphere.

A single dark chocolate bar made with cocoa from deforestation produces the same amount of carbon pollution as driving 4.9 miles in a car.

In Switzerland, life is rich and sweet.

In Côte d’Ivoire, life is poor and sour.

In Canada, a remembered jingle asks:

“When you eat your Smarties, do you eat the red ones last?

Do you suck them very slowly or crunch them very fast?

It’s candy and milk chocolate, so tell me when I ask:

When you eat your Smarties, do you eat the red ones last?”

An important question for these dark and bitter times, eh?

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / Facebook / The Rough Guide to Switzerland / Lonely Planet The World / Lonely Planet Africa on a Shoestring / Etelie Higonnet, Marisa Bellantonio and Glenn Hurowitz, Mighty Earth, Chocolate’s Dark Secret: How the Cocoa Industry Destroys National Parks / http://www.dicconbewes.ch / http://www.lindt-experience.ch / http://www.maestrani.ch

.JPG?h=1080&w=1920&auto=format&fit=crop&q=40)

.JPG?h=1080&w=1920&auto=format&fit=crop&q=40)