Landschlacht, Switzerland, 30 June 2018

“Writing a blog about everything that happens to you will honestly help here.” (Therapist)

“Nothing happens to me.”(John Watson, MD)

(“A Study in Pink“, Sherlock)

Two months ago (30 April) I began this post.

Four days later I was involved in an accident resulting in both arms broken.

After 3 weeks in hospital and 4 weeks in a rehab centre and 2 weeks at home, I am finally able to resume this post.

(My other blog is only a month and a half behind, so I am making progress!)

Landschlacht, Switzerland, 30 April 2018

I am certain that what I am feeling this morning isn´t unique to myself.

That feeling that my life isn´t completely my own.

That I am being pulled and propelled by others in directions that I would rather choose for myself.

There are the obligations of work where employers view employees as mere tools towards their profits or obstacles carelessly removed when those profits are threatened.

There are the obligations of relationships where everyone wants your time and attention and feels slighted if your time and attention is considered more important to you than their own.

There are times when I can really relate to the words of Dido Armstrong….

“If my life is for rent….

….I deserve nothing more than I get

Cos nothing I have is truly mine.

I´ve always thought that I would love to live by the sea.

To travel the world alone and live more simply.

I have no idea what´s happened to that dream.

Cos there´s really nothing left here to stop me.

It´s just a thought, only a thought….

While my heart is a shield and I won´t let it down.

While I am so afraid to fail so I won´t even try.

Well, how can I say I´m alive?”

This song comes back to me each time I have the feeling of being a voyeur of my own life.

And as the jukebox of my mind plays this song I am reminded of particular moments in London….

London, England, 25 October 2017

She was there for a medical conference.

I was there to carry her bags.

Or so it felt at times.

We had only a week to explore London (23 – 29 October).

Her conference was Thursday to Saturday 26 – 28 October, which meant from Monday to Wednesday and on Sunday I would need to accommodate her wishes and make them my own for the sake of marital bliss.

(Ain´t love grand?)

It wasn´t Thursday yet, so serendipitious exploration by myself wasn´t in the cards this day.

She was determined to see absolutely everything she could while she could and liked having me around to carry our half dozen guidebooks and the liquid refreshment and the various odds and ends tourists insist they overpack their daybags with.

We found ourselves in the section of London known as Smithfield….

“The ground was covered, nearly ankle-deep with filth and mire, a thick steam perpetually rising from the reeking bodies of the cattle and mingling with the fog.”

(Oliver Twist, Charles Dickens)

Smithfield is a corruption of “smooth field“, originally open ground outside the city walls, a flat marshy area stretching to the eastern bank of the Fleet River.

Very little of early medieval London remains intact today, because Londoners built houses of wood.

The City burned down in 1077, 1087, 1132, 1136, 1203, 1212, 1220 and 1227.

Almost anything left intact was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

What has survived was begun by a fool.

The great Priory of Saint Bartholomew along with St. Bartholomew´s Hospital was founded in the 12th century by Rahere when Henry I (1068 – 1135), a son of William the Conqueror, was King.

Almost all that is known about Rahere comes from the Book of Foundation.

Rahere´s family was poor, but he was intelligent and ambitious so over time he would acquire rich and powerful friends.

His cheerful and fun-loving character made him popular and he soon became part of Henry I´s court as the king´s jester.

The whole royal household was thrown into grief and gloom when the White Ship bearing the King´s heir and a number of his friends was lost with all hands on board in a winter storm in November 1120.

Henry never smiled again and Rahere became a priest.

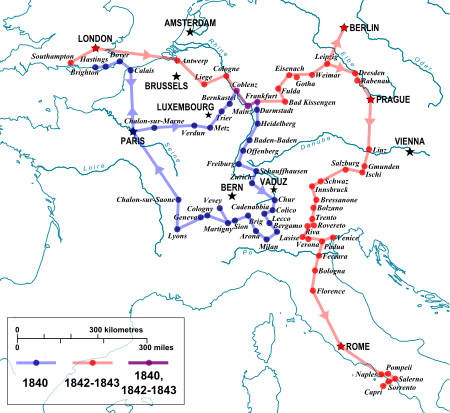

Rahere decided to go on a pilgrimage to Rome, a long and difficult journey by sea or land in those days, controlled by wind and weather and the speed of a sail or a horse, taking a month or more.

Rahere visited various places in Rome associated with St. Peter and St. Paul but then he fell dangerously ill with malaria and was nursed at the Hospital of San Giovanni di Dio on Isola Tiberina by the Brothers of the Order of St. John of God.

If the Book of Foundation is to be believed, in his sickness Rahere vowed that if he would regain his health he would return to England and “erect a hospital for the restoration of poor men.”

Rahere´s prayer was answered and he soon set off for England.

On the way home he had a terrible dream in which he was seized by a beast with four feet and two wings who lifted him up high and placed him on a ledge above a yawning pit.

Rahere cried out in fear of falling and a figure appeared at his side who identified himself as St. Bartholomew and said he had come to help him.

In return the Saint said:

“In my name, thou shalt found a church that shall be a House of God in London at Smithfield.”

So, according to the legend, that´s just what Rahere did.

Rahere´s fabled miraculous return to good health contributed to the priory gaining a reputation for curative powers, with sick people filling the church of St. Bartolomew the Great, notably on 24 August (St. Bartholomew´s Day).

As Smithfield was part of the King´s market the King´s permission was needed.

A Royal Charter was drawn up (1122) to found a priory of Augustinian canons and a hospital.

Building began in March 1123.

The ghost of Rahere is reputed to haunt St. Bartholomew´s, following an incident during repair work in the 19th century when his tomb was opened and a sandal removed.

The sandal was returned to the church but not Rahere´s foot.

Since then, Rahere is a shadowy, cowled figure that appears from the gloom, brushes by astonished witnesses and fades slowly into thin air.

Rahere is said to appear every year on the morning of 1 July at 7 a.m., emerging from the vestry.

Bartholomew Fair was established in 1133 by Rahere to raise funds.

Rahere himself used to perform juggling tricks.

(Samuel Pepys would later write about seeing a horse counting sixpence and a puppet show of Ben Jonson´s 1614 play Bartholomew Fair.)

In Daniel Defoe´s Moll Flanders (1722) his heroine meets a well-dressed gentleman at the Fair.

William Wordsworth´s poem The Prelude (1803) mentions the din and the Indians and the dwarfs at the Fair.

Victorians would close the Fair down in 1855 to protect public morale.

It was felt that the Fair was encouraging debauchery and public disorder.

The Newgate Calendar wrote that the Fair was “a school of vice which has initiated more youth into the habits of villainy than Newgate Prison itself.”)

Hidden in the back streets north of the namesake hospital, St. Bartholomew the Great is London´s oldest and most atmospheric parish church.

Begun in 1123 as the main church of St. Bartholomew´s priory and hospice, it was partly demolished in the Reformation and gradually fell into ruins.

The church once adjoined the hospital and though the hospital mostly survived the Dissolution of the Monasteries, about half of the church was ransacked before being demolished in 1543.

In the early 16th century, Prior William Bolton had an oriel window installed inside the church so he could keep an eye on the monks.

The symbol in the centre panel is a crossbow (bolt) passing through a barrel (tun) in honour of the Prior.

Having escaped the Great Fire of 1666, the church fell into disrepair.

The cloisters were used as a stable, there was a boys´ school in the triforium, a coal and wine cellar in the crypt, a blacksmith´s in the north transept and a printing press where Benjamin Franklin served for a year (1725) as a journeyman printer in the Lady Chapel.

The church was also occupied by squatters in the 18th century.

From 1887, Aston Webb restored what remained and added the chequered patterning and flintwork that now characterizes the exterior.

The Church of Saint Bartholomew the Great is a rare survivor, despite also suffering Zeppelin bombing in World War I and the Blitz in World War II.

To get an idea of the scale of the original church, approach it through the half-timbered Tudor gatehouse on Little Britain Street.

A wooden statue of St. Bartolomew stands in a niche.

Below is the 13th century arch that once formed the entrance to the nave.

The churchyard now stands where the nave once was.

There is also the bust of Edward Cooke made of “weeping marble“, stone that appears to cry if the weather is wet enough and when the central heating hasn´t dried out the stone.

The inscription beneath the statue exhorts visitors to “unsluice your briny floods.”

One side of the cloisters survives to the south and now houses the delightful Cloister Café.

Under a 15th century canopy north of the altar is the tomb of Rahere.

The poet and heritage campaigner John Betjeman (1906 – 1984) kept a flat opposite the churchyard on Cloth Fair.

Betjeman considered St. Bartolomew the Great to have the finest surviving Norman interior in London.

Charity in the churchyard on Good Friday still continues.

A centuries-old tradition began when 21 sixpences were placed upon the gravestone of a woman who had stipulated in her will that there would be an annual distribution to 21 widows in perpetuity.

Freshly baked hot cross buns nowadays are not only to widows but to others as well.

In 2007 the church became the first Anglican parish church to charge admission to tourists not attending worship.

St. Bartholomew the Great is the adopted church of the Worshipful Companies of Butchers, Founders, Haberdashers, Fletchers, Farriers, Farmers, Information Technologists, Hackney Carriage Drivers and Public Relations Practitioners.

Perhaps it is this last Company combined with the church´s atmosphere that has made St. Bartholomew´s much beloved of film companies.

The fourth wedding of the film Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994) sees Charles (Hugh Grant) deciding to marry ex-girlfriend Henrietta (Anna Chancellor) aka “Duck Face“.

However, shortly before the ceremony at St. Bartholomew, Charles´ ex-casual girlfriend Carrie (Andie MacDowell) arrives, revealing to Charles that she and Hamish (Corin Redgrave) are separated.

Charles has a crisis of confidence, which he reveals to his deaf brother David (David Bower) and his best friend Matthew (John Hannah).

During the ceremony, when the vicar asks whether anyone knows a reason why the couple should not marry, David, who was reading the vicar’s lips, asks Charles to translate for him and says in sign language that he suspects the groom loves someone else.

The vicar asks whether Charles does love someone else and Charles replies, “I do.”

Henrietta punches Charles and the wedding is halted, with the church forgotten for the rest of the film.

In Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, the Sheriff of Nottingham (Alan Rickman) “marries” Maid Marion (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) in this church meant to be the chapel of Nottingham Castle.

William Shakespeare (Joseph Fiennes) reveals to Viola de Lesseps (Gwyneth Paltrow) that he is alive when he surprises her and her husband-to-be Lord Wessex (Colin Furth) inside St. Batholomew´s. (Shakespeare in Love)

Sarah Miles (Julianne Moore) regularly visits Father Smythe (Jason Isaacs) at the church. (The End of the Affair, 1999)

William Wilburforce (Ioan Gruffuff)(1797 – 1833) finds spiritual enlightenment in St. Bart´s to inspire him to devote his life to the abolishment of slavery in England. (Amazing Grace)

Anne Boleyn (Natalie Portman) marries King Henry VIII (Eric Bana) and is crowned Queen of England in a ceremony at St. Bartholomew, as is Snow White (Kristen Stewart). (The Other Boleyn Girl)(Snow White and the Huntsman)

The interiors of Fotheringray Castle and Chartley Hall (the former where Mary, Queen of Scots (1542 – 1587) was imprisoned, the latter from where she reigned, both ruins) are captured by St. Bartholomew´s. (Elizabeth: The Golden Age)

Sherlock Holmes (Robert Downey Jr.) and Dr. John Watson (Jude Law) with Inspector Lestrade (Eddie Marsan) and his police force battle Lord Blackwood (Mark Strong) and his men within St. Bartholomew`s. (Sherlock Holmes, 2009)

St. Bart´s has also been used in Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015), Transformers: The Last Knight (2017), the TV series Taboo and as a stand-in for Westminster Abbey by T-Mobile for its “royal wedding” advertisement (2011).

Historically much blood has been spilt in Smithfield, with both the living their lives dispatched and the dead their bodies snatched.

Blood, both animal and human, has been spilled at Smithfield for centuries that.

Given its ease of access to grazing and water, Smithfield established itself as London´s livestock market, remaining so for almost a thousand years.

The meat market grew up adjacent to Bartholomew Fair, though it wasn´t legally sanctioned until the 17th century.

Live cattle continued to be herded into Smithfield until the Fair was suppressed and the abattoirs moved out to Islington.

A new covered market hall was erected in 1868 and it remains London´s main meat market.

Early morning by 7 am, Smithfield Market is at its most animated with a full range of stalls open.

Human blood was often spilled in Smithfield as well.

William Wallace (1270 – 1305), a Scottish knight and one of the main rebel leaders during the Wars of Scottish Independence, was captured near Glasgow, transported to London and taken to Westminster Hall.

There he was tried for treason and for atrocities against civilians in war, “sparing neither age nor sex, monk nor nun“.

He was crowned with a garland of oak to suggest he was the King of Outlaws.

Wallace responded to the treason charge:

“I could not be a traitor to King Edward, for I was never his subject.”

Following his trial, Wallace was taken from the Hall to the Tower of London on 23 August 1305.

He was then stripped naked and dragged through the city at the heels of a horse to Smithfield.

He was strangled by hanging but released while he was still alive.

He was then emasculated, eviscerated and his bowels burned before him.

Wallace was then beheaded, drawn and quartered.

His head was preserved (dipped in tar) and placed on a pike atop London Bridge.

In 2005 a memorial service was held for Wallace, on the 700th anniversary of the Scottish rebel´s execution.

Above: Plaque on the wall of St. Bartholomew´s Hospital, marking the place of Wallace´s execution

Wat Tyler led the Peasants´ Revolt in 1381.

At the height of the Revolt, Tyler had them gather, 20,000 strong, at Smithfield after having just taken London by storm.

They assembled to discuss what their next move should be.

They were debating whether to loot the city when the King appeared, accompanied by a retinue of 60 horsemen.

Though Richard II was only a boy of 14, he did not shrink from the challenge.

When he reached the Abbey of St. Bartholomew, Richard stopped and looked at the great crowd and said he would not go on without hearing what they wanted.

If they were discontented, he would placate them.

Tyler, a roofer from Kent, emboldened by the peasants´ success, rode forward to negotiate with the King.

He spoke insolently to the King and to the Lord Mayor of London who was with him.

In reply, the Lord Mayor produced his sword and struck Tyler in the head.

Tyler fell to the ground and was surrounded by the King´s retainers who finished him off while the peasants looked on helplessly.

They were about to launch into a massacre when Richard hurriedly retrieved the situation.

Ordering his retainers to stay where they were, Richard rode forward alone and calmed the mob.

He told them:

“I am your King.

You have no other leader but me.”

The crowd dispersed, the Revolt was over, the peasants went home, their remaining leaders hunted down and hanged without mercy.

Smithfield became a regular venue for public executions.

The Bishop of Rochester´s cook was boiled alive here in 1531, after being found guilty of poisoning.

The local speciality was burnings, reaching a peak during the reign of “Bloody” Mary in the 1550s when hundreds of Protestants were burnt at the stake for their beliefs, in revenge for the Catholics who had suffered a similar fate under Henry VIII and Edward VI.

A plaque on the side of the church commemorates those who died at Smithfield as martyrs for their faith – 50 Protestants and the religious reformers who would be called “the Marian martryrs“.

“It is foolish, generally speaking, for a philosopher to set fire to another philosopher in Smithfield Market because they do not agree in their Theory of the universe.

That was done very frequently in the last decadence of the Middle Ages and it failed altogether in its object.” (G.K. Chesterton)

On 16 July 1546, Anne Askew of Lincolnshire and three men were burnt at the stake, for going around London distributing Protestant tracts and giving them secretly to the ladies of the Queen´s household.

Askew was arrested, tortured in the Tower of London and then executed.

She was 25.

So many executions….

Reportedly some nights there is a strong scent of burning flesh.

During the 16th century the Smithfield site was the place of execution of swindlers and coin forgers who were boiled to death in oil.

After 1783, when hangings at Tyburn Tree (present site of Marble Arch) stopped, public executions at the nearby gates of Newgate Prison just south of Smithfield, began to draw crowds of 100,000 and more.

The last public beheading took place here in 1820 when five Cato Street Conspirators were hanged and decapitated with a surgeon´s knife.

It was in hanging that Newgate excelled.

Its gallows dispatched 20 criminals simultaneously.

Unease over the “robbery and violence, loud laughing, oaths, fighting, obscene conduct and still more filthy language” that accompanied public hangings drove the executions inside the prison walls in 1868.

The bodies of the executed were handed over to the surgeons of St. Bartholomew´s for dissection, but body snatchers also preyed on non-criminals buried in the nearby churchyard of St. Sepulchre-without-Newgate.

Such was the demand for corpses that relatives were forced to pay a night watchman to guard the graveyard in a specially built watchhouse to prevent the “Resurrection Men” from retrieving their quarry.

Successfully stolen bodies were taken to the nearby tavern, the Fortune of War, to be sold to the physicians of the St. Bartolomew´s Hospital.

Rahere may have been both head of the Priory and master of the Hospital, but soon these offices, these institutions became distinct identities.

St. Bart´s Hospital wasn´t the first of its kind, for it, like the earliest Hospitals, was a part of a monastery that gave shelter and food to wayfarers, serving both as guesthouse and infirmary, caring not just for the traveller, but for all kinds of needy people, including the sick, the aged and the destitute.

St. Bart´s would become known for taking in expectant mothers, foundlings and orphans and babies from nearby Newgate Prison.

St. Bart´s began with eight brethern and four sisters, all following the rule of the Augustinian order.

For over four centuries, the Hospital continued to be a religious institution.

By 1150, St. Bart´s had become a popular refuge for the chronically ill, many seeking miraculous cures, yet little is known about these patients in medieval times, other than those described in the Book of the Foundation.

A carpenter named Adwyne was brought in suffering from chronic contractions resulting from prolonged illness.

First he regained use of his hands by making small tools and as his limbs became stronger he was able to use an axe.

His recovery has much in common with modern physiotherapy and occupational therapy.

Gradually, treatments based on medical doctrines were introduced.

John Mirfeld, a contemporary of Chaucer, lived within the Priory and was closely connected to the Hospital.

He wrote two books in which he recorded everything he believed conducive to spiritual and physical health.

The first of his works, the Breviarium Bartholomei (Breviary of Bartholomew), written in Latin between 1380 and 1395, is a large compendium of diagnoses, treatments and remedies, which were copied from the standard medical authorities of the day, mainly classical and Arabic, but included cures based on folklore and magic which were an integral part of medieval medicine.

Mirfield´s writings were the best available medical practice 600 years ago.

The Breviarium Bartholomei dealt with general illnesses, then categorized other diseases according to the parts of the bodies they affected.

The Order of the Hospital (1552) stated that there should be “one fayre and substantial chest” in which the Hospital´s records were kept.

The chest was to have three locks, which only the president, treasurer and one other governor had the key to a lock.

The Clerk of the Hospital was responsible for writing down a record of the Hospital´s business, for which he kept four books: a repertory (copies of all deeds relating to the Hospital´s property, rights and obligations), a book of survey (the names of all the tenants of the Hospital´s properties and who was responsible for repairs), a book of accounts / the ledger (copies of all deeds relating to the Hospital´s property, rights and obligations), and a journal (a record of the meetings of the hospital´s governers).

From 1547 there were usually three Hospital surgeons, each in regular attendance on the patients.

Some of the early surgeons at St. Bart´s were skilled practitioners and highly distinguised in their day.

William Clowes (1544 – 1604) wrote a number of books which have been described as the best surgical texts of the Elizabethan age.

Above: William Clowes

John Woodall (1556 – 1643), a contemporary of William Harvey, wrote The Surgeon´s Mate, a book full of sound and practical advice for ships´ surgeons.

Woodall was one of the first to recognize scurvy (caused by a lack of Vitamin C in the diet) and lemon juice as a treatment for it.

Above: John Woodall

The most common operations were: amputations, lithothomy (removing bladder stones) and trephination (drilling with a circular saw to remove portions of the skull.

But without anaesthetics and any understanding of the causes of infection, pus in wounds was accepted as part of the healing process and mortality rates were high.

More typically, surgeons dealt with accidents such as burns, fractures, knife and gunshot wounds.

They also pulled teeth, lanced boils, drained pus, treated skin disorders, venereal infections, tumours and ulcers.

Most drugs were made from home-grown and imported plants and spices and were based on traditional remedies.

In 1618 the first London Pharmacopoeia was published and sponsored by the Royal College of Physicians, embodying a list of approved drugs and the methods of preparing them.

Some exotic substances were included, such as unicorn´s horn and spider´s web, reflecting the practices of the time.

One of the more distinguished apothecaries at St. Bart´s was Francis Bernard (1627 – 1698) who amassed a huge library, containing 13,000 volumes, 4,500 of which related to medicine and science, at his house in Little Britain near the Hospital.

Pharmacy changed slowly and it was not until the 19th century that scientific analysis began to isolate drugs like morphine, codeine and quinine.

Unlike surgeons who acquired their skills by apprenticeship, physicians were university trained.

Until the 17th century, medicine remained largely backward looking, dependent upon classical authorities and ancient remedies.

Diagnosis was made by taking into account the patient´s history, lifestyle and appearance, and external factors such as the environment in which the patient lived.

Gradually, however it became accepted that the human body could be investigated by dissection and that knowledge of anatomy was vital in understanding how the body worked.

William Harvey (1578 – 1637) studied medicine and anatomy at the famed University of Padua before serving as physician at St. Bart´s.

Above: William Harvey

He is credited with one of the greatest advances in medical history: the discovery of the circulation of the blood, published in 1628 in Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cardis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (An Anatomical Essay on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals).

Based on his observations and experiments, Harvey demonstrated that the blood circulated constantly around the body, pumped by the heart, going out by the arteries and returning by the veins.

His work was a role model for scientific investigation.

Nonetheless by the 18th century there was still no real understanding of the nature and causes of disease.

Peter Mere Latham (1789 – 1875) emphasized the careful physical examination of the patient.

Above: Peter Mere Latham

Some 60 volumes of his casenotes, all carefully indexed, are the earliest examples of detailed patient records.

Diagnosis using instruments, such as the stethoscope, was introduced in the first half of the 19th century.

Percivall Pott (1714 – 1788) bridged the gap between the barber-surgeons and the modern art of surgery.

Known for his consideration of the patient and who described amputation as “terrible to bear and horrible to see“, Pott introduced many improvements to surgery and helped raised the standing of his procession.

By the last quarter of the 18th century, systematic medical education (the mix of university education and hands-on apprenticeship) had yet to be introduced in England.

Due to popularity of anatomical, surgical operations and bandaging lectures, the Hospital began to provide a purpose-built lecture theatre.

A wide range of subjects was taught including theory and practice of medicine, anatomy and physiology, surgery, physics, chemistry, materia medica (drugs), midwifery and diseases of women and children.

By 1831, St. Bart´s had the largest medical school in London, providing a complete curriculum for students preparing for medical examination.

Health care was transformed in the 19th century.

New specialities arose as medicine became a science.

By the end of the century, research, often conducted in the laboratory, had become the basis of medical science.

A story, a legend, begins in 1881, when Dr. John Watson, having returned to London after serving in the Second Anglo-Afghan War, visits the Criterion Restaurant and runs into an old friend named Stamford, who had been a dresser under him at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital.

St. Bart´s was Watson´s alma mater.

Watson confides in Stamford that, due to a shoulder injury that he sustained at the Battle of Maiwand, he has been forced to leave the armed services and is now looking for a place to live.

Stamford mentions that an acquaintance of his, Sherlock Holmes, is looking for someone to split the rent at a flat at 221B Baker Street, but he cautions Watson about Holmes’s eccentricities.

Stamford takes Watson back to St. Bartholomew’s where, in a chemical laboratory, they find Holmes experimenting with a reagent, seeking a test to detect human haemoglobin.

Holmes explains the significance of bloodstains as evidence in criminal trials.

“There´s the scarlet thread of murder running through the colourless skein of life.” (Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarlet)

After Stamford introduces Watson to Holmes, Holmes shakes Watson’s hand and comments, “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.”

Though Holmes chooses not to explain why he made the comment, Watson raises the subject of their parallel quests for a place to live in London, and Holmes explains that he has found the perfect place in Baker Street.

At Holmes’s prompting, the two review their various shortcomings to make sure that they can live together.

After seeing the rooms at 221B, they move in and grow accustomed to their new situation.

Pathology (the study of the underlying causes and processes of disease) was at first the main area of scientific work.

Case notes of individual patients were systematically compiled, not only as a record of diagnosis and treatment, but also for use in teaching and research.

Gradually, the old beliefs that infection arose spontanteously gave way to the discovery that disease was caused by small living germs (bacteria).

With the introduction of anaesthetics and antiseptics, procedures could be undertaken that were formerly prohibited by the risk of blood loss, infection and the suffering of the patient.

So while the number of operations performed at St. Bart´s increased dramatically, the overall mortality rate kept falling.

During the 1930s, St. Bart´s led the world in the development of mega-voltage X-ray therapy for cancer patients and was the first Hospital to install equipment capable of treating tumours with a 1,000,000 volt beam.

St. Bartholomew´s Hospital has existed on the same site since its founding in the 12th century, surviving both the Great Fire of London and the Blitz, making this Hospital the oldest in London.

St. Bartholomew´s Hospital Museum, open Tuesday to Friday, 10 am to 4 pm, shows how medical care has developed and the history of the Hospital.

The Museum is part of the London Museums of Health and Medicine and has been described as one of the world´s 10 weirdest medical museums.

Among the medical artifacts are some fearsome amputation instruments, a pair of leather “lunatic restrainers” and jars with labels such as “Poison – for external use only.”

The Museum contains some fine paintings, gruesome surgical tools and a tribute to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who wrote some of his Sherlock Holmes stories while studying medicine here.

“You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.“

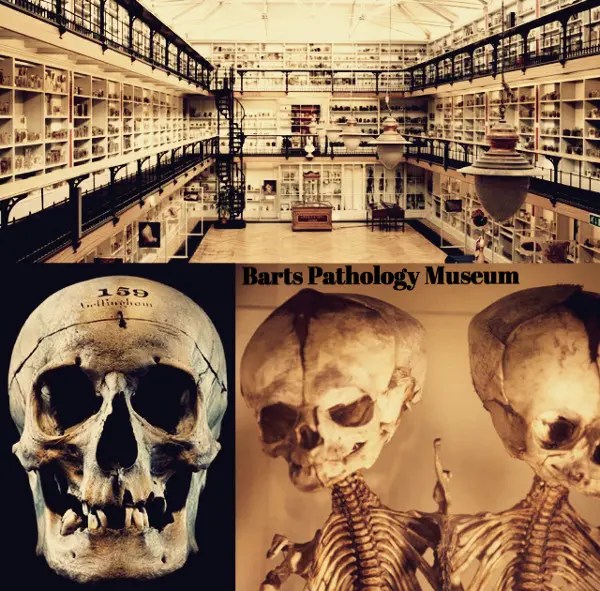

Upstairs on the 3rd floor of the Hospital, the Barts Pathology Museum (http://www.qmul.ac.uk/bartspathology) is a cavernous, glass-roofed hall lined with jars of pickled body parts, open to the visitor by appointment only.

Around 5,000 diseased specimens in various shades of putrid yellow, gangerous green and bilious orange are neatly arranged on three open-plan floors linked by a spiral staircase.

Only the ground floor of the Museum is open to the public, while the upper galleries are reserved for teaching, cataloguing and conservation.

Some favourites: the deformed liver of a “tight lacer“(corset wearer), the misshapen bandaged foot of a Chinese woman, the skull of the assassin John Bellingham who murdered Prime Minister Spencer Perceval.

The Museum has a series of workshops and talks inspired by its collection.

There are taxidermy classes, lectures on funerary cannibalism and the history of syphilis, and festivals dedicated to bodily decay and broken hearts.

Have a glass of wine amongst severed hands and trepanned skulls.

If you dare….

Prior to the Anatomy Act of 1832, there were only two ways in which medical schools could acquire corpses: prisoners sentenced to death and dissection, or corpses purchased from the “Resurrection Men” body snatchers.

A door leads from the Hospital Museum to the Hospital´s official entrance hall.

On the walls of the staircase are two murals painted by William Hogarth: The Pool of Bethesda and The Good Samaritan, which can only be seen at close quarters on Friday afternoons.

Hogarth was so enraged by the news that the Hospital was commissioning art from Italian painters that he insisted on doing the staircase murals for free as a demonstration that English painting was equal to Italian.

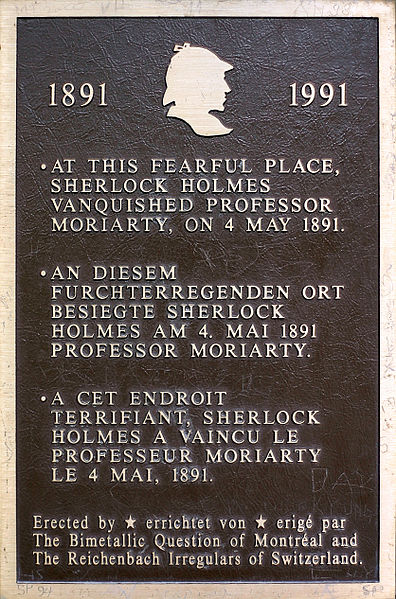

The legend recreated in the BBC drama, final episode “The Reichenbach Fall” of the second series of Sherlock.

J.M.W. Turner, “Reichenbach Falls”

John finds Sherlock at the St. Bartholomew’s lab but leaves after hearing Mrs. Hudson has been shot.

Sherlock texts Moriarty who meets him on the roof of the hospital to resolve what the criminal calls their “final problem“.

Moriarty reveals that Sherlock must commit suicide or Moriarty’s assassins will kill John, Mrs. Hudson, and Lestrade.

Sherlock realises that Moriarty has a fail-safe and can call the killings off.

Sherlock then convinces Moriarty that he is willing to do anything to make him activate the fail-safe.

After acknowledging that he and Sherlock are alike, Moriarty tells Sherlock “As long as I am alive, you can save your friends,” then commits suicide by shooting himself in the mouth, thereby denying Sherlock knowledge of the abort codes and the ability to prove that Moriarty does exist.