Landschlacht, Switzerland, 4 November 2017

Three thoughts come to my mind when associated with the words “sealed train”:

- Easter Monday, 9 April 1917, when Lenin boarded a sealed train in Zürich bound for Petrograd (today´s St. Petersburg), which Winston Churchill described: “The Germans transported Lenin in a sealed train like a plague bacillus from Switzerland into Russia.”

- The dark days of World War II when Jews and other “undesirables” were herded into sealed train boxcars bound for concentration camps like Auschwitz

- My own adventures in America where I rode empty boxcars in Alabama and was threatened to be shot for trying to sleep under one in Maine

Thoughts #2 and #3 will be left for future posts….

Zürich, Switzerland, 2 March 1917

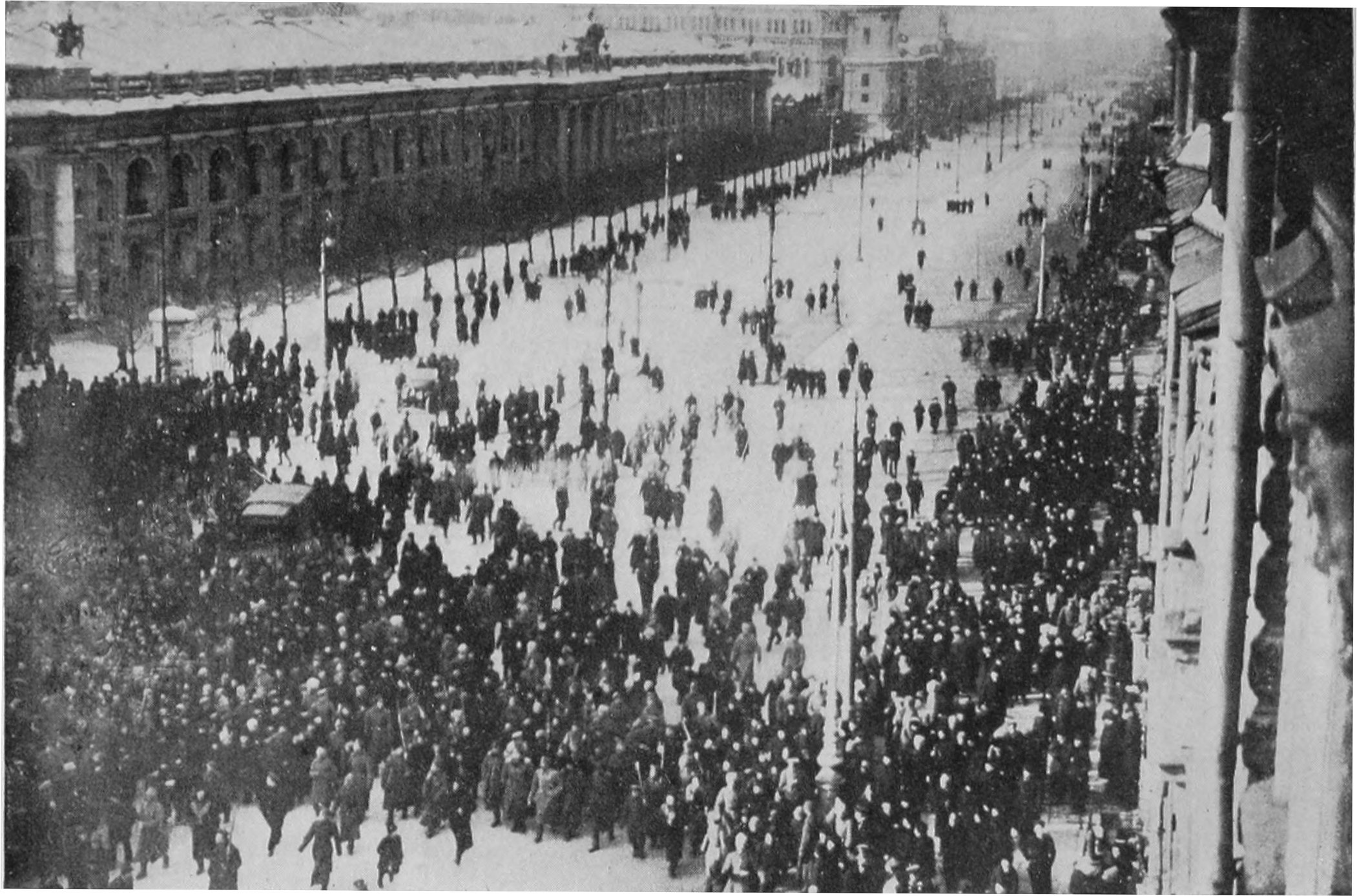

The news of the February Revolution came as just as much as a surprise to Lenin as to everyone else in Europe.

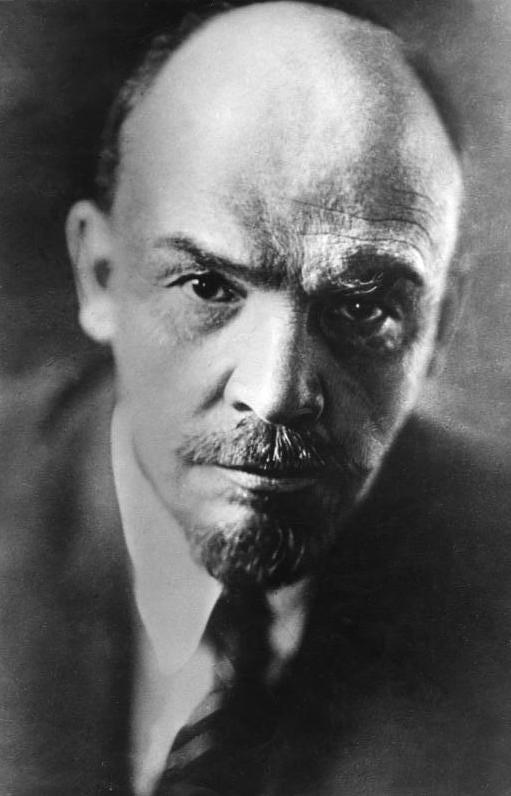

The outbreak of the February Revolution found V.I. Lenin in Zürich, where he and his wife Krupskaia had lived, in a single-room apartment in Spiegelgasse across the street from a sausage factory, since February 1916.

Above: Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov aka Lenin (1870 – 1924)

(See Canada Slim and the Bloodthirsty Redhead, ….and the Zimmerwald Movement, ….and the Forces of Darkness, ….and the Dawn of a Revolution, ….and the Bloodstained Ground, ….and the High Road to Anarchy, ….and the Birth of a Nation, ….and the Coming of the Fall, ….and the Undiscovered Country of this blog for background on how Lenin came to be living in Switzerland and the events in Switzerland and Russia that lead to today´s story….)

The Polish revolutionary Bronsky first brought Lenin the news of insurrection in Petrograd, stopping by Lenin´s Spiegelgasse flat as Lenin and his wife were leaving for the library.

Above: The Lenins lived on the 2nd floor here at Spiegelgasse 14, Zürich

The effect had been like an electric current.

Lenin paced and shouted and punched the air.

“Staggering! Such a surprise! We must go home. It´s so incredibly unexpected.”

But the only journey he could make in the short term was down the steep lane to the shore of the Zürichsee, where there were kiosks with a good range of the latest Swiss and foreign newspapers.

He read about it in the Zürich papers, but this is not to say that he was unprepared to take advantage of it.

Lenin had been quietly receiving subsidies from the German government since 1916, when the socialist agent Parvus had first advised Berlin to give Lenin and his Bolsheviks financial support.

(Lenin´s apologists later made much ado out of the agonies Lenin supposedly went through before “allowing” the Germans to send him back to Russia.)

Before the news of the Revolution broke, Lenin´s wife had likened him to the white wolf they had once seen in the London Zoo, the one creature among the tigers and the bears that never grew accustomed to its confinement.

Above: An Arctic wolf

But now his frustration was intolerable.

“It´s simply shit!”, Lenin spluttered after reading a report of recent speeches in the Soviet.

“I repeat: shit!”

Whenever he picked up a pen that March, he might as well have drawn a pin from a grenade.

The news from Petrograd had shaken the entire Russian community in Switzerland.

Above: The flag of Russia

Russia had become the freest country in the world as the new government granted an amnesty for political prisoners, abolished the death penalty and dissolved what was left of the Tsar´s secret police.

The Russian consulate in Davos held a reception to greet the new age of liberty and many of the small foundations that supported refugees began to talk of immediate repatriation.

There were 7,000 Russian nationals in Switzerland, and their welcome was wearing thin, but there still was no easy way to get back home.

Above: The flag of Switzerland

The newspapers followed the drama of the Revolution day by day, but the trouble was that Lenin remained the comrade who was watching “from afar”.

“You can imagine what torture it is for all of us to be stuck here at a time like this. We have to go by some means, even if it is through Hell.”

(Lenin´s letter to Yakov Fürstenberg, 11 March 1917.)

There was only one option.

The Swiss exiles would have to travel across Germany to the Baltic coast and from there to Sweden, Finland and home to Russia.

Above: The flag of Germany (1871 – 1918)

The German government was convinced that the financing of extreme elements would hasten Russia´s disintegration and end their war on the eastern front.

Two weeks passed since the abdication of the Tsar.

Above: Nicholas II (1868 – 1918), Tsar of Russia (1894 – 1917)

Conditions were agreed upon between Lenin and the German government:

His train carriage would have the status of an extra-territorial entity.

Only Swiss socialist Fritz Platten would have contact between the Russian passengers and their German guards.

No one would enter the exiles´ carriage without permission.

As far as possible, the carriage was to travel without stops.

No passenger could be ordered to leave.

There would be no control of passports and no discrimination against potential passengers on the grounds of their political views.

At the last moment, permission was secured for the group to bring its own food.

News of Lenin´s negotiations spread through Zürich´s cafés within hours.

Irish author James Joyce, who heard the story over a drink, thought that the proposed safe passage was proof that the Germans “must be pretty desperate”.

Above: James Joyce (1882 – 1941)

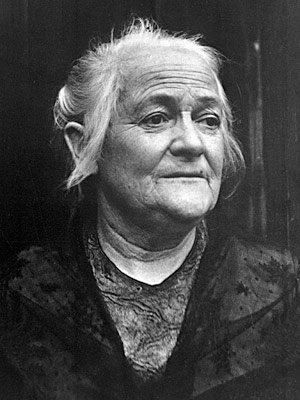

French novelist Romain Rolland dismissed Lenin and his aspiring fellow passengers as nothing more than instruments of Europe´s enemy.

Above: Romain Rolland (1866 – 1944)

The 8th of April 1917 was Easter Sunday in Switzerland, and the authorities hoped to have the Russians packed on their train before the holiday began.

Instead, that weekend was the most frantic of all.

To make the whole business more difficult, a chorus of abuse accompanied the travellers´ every move.

With plenty of time on their hands, emigrés who were still waiting for a formal invitation from Russia´s Provisional Government joined forces with centre-left Swiss in calling Lenin a traitor.

For the Germans, it was important that the military should approve the precise route from the Swiss border.

Russian-speaking German guards were to be discreetly travelling inside the carriage “for security”.

“The émigrés expect to encounter extreme difficulties, even legal persecution, from the Russian government because of travel through enemy territory. It is therefore essential that they be able to guarantee not to have spoken with any German in Germany.”

(Gisbert von Romberg, Bern consulate, cable to Berlin, 9 April 1917)

Zürich, Switzerland, Easter Monday, 9 April 1917

The travellers gathered in the Zähringerhof, the hotel on the square outside Zürich´s classical railway station.

(Today it is called the Schweizerhof.)

Thirty-two adults were set to travel.

The last thing to be done before leaving Zürich was to eat lunch, a noisy banquet in the Zähringerhof that was accompanied by speeches of farewell.

It was Lenin´s final chance to win over the many critics who were still trying to prevent the trip.

Lenin predicted a worldwide revolution that would sweep away “the filthy froth on the surface of the world labour movement”.

“The objective circumstances of the imperialist war make it certain that the revolution will not be limited to Russia….

Transformation of the imperialist war into civil war is becoming a fact.”

They were returning to their homeland, despite the threat of jail that awaited them.

Every passenger knew the conditions.

Every passenger accepted the risks.

Shouts and hisses followed them across the square as the travellers made for their first train.

Zürich, Switzerland, 11 September 2017

This was a rare opportunity.

Between my August trip in Italy and my October trip in London, between work as a teacher (albeit too little work) and work as a barista for Starbucks St. Gallen, I finally had time today to follow Lenin´s route from Zürich to the Swiss border.

I was not unsympathetic to those sadly remembering the anniversary of 9/11, but I felt that the story I had been following of the events leading to Lenin on the train needed to be personally experienced a century later to compare events of yesteryear with the realities of today.

What was it like to travel from Zürich to Singen, following the rail route that Lenin and his fellow travellers took?

I left Landschlacht this morning at 0909, then once in Zürich I bought the day´s New York Times and then walked to the Café Odeon at Limmatquai 2, one of Lenin´s favourite haunts.

Above: Café Odeon and Odeon Apotheke, corner of Limmatquai and Rämistrasse

The place still appears much as it did when Lenin frequented the place, although the clientele has changed considerably since then.

The decor remains Art Nouveau in style, with rich red upholstery, sparkling chandeliers, and brass and marble fittings.

Listing the names of all the writers, poets, painters and musicians who came and went in the Odeon would certainly render a valuable cross-section of the celebrities of well over half a century.

Only a few of those who thronged there and gave the Odeon its reputation of an intellectual meeting place are mentioned here:

Franz Werfel, the Austrian poet and storyteller who had come to Zürich in 1918 to perform his play “The Trojan Women”, which led to peace demonstrations as there had never been before.

Above: Franz Werfel (1890 – 1945)

Stefan Zweig, Frank Wedekind and Karl Kraus, author of Torch, as well as William Somerset Maugham, the author of plays and short stories….

Erich Maria Remarque, the writer of the anti-war novel All Quiet on The Western Front also belong to them.

Above: Erich Maria Remarque (1898 – 1970)

Then come Kurt Tucholsky, Rowohlt, Klaus Mann and Alfred Kerr, not to forget the Irish author James Joyce, who spent a total of about five years in Zürich, of which countless hours were at the Odeon.

In his books, names of Zürich’s streets and squares, bars or people appeared over and over again – in encrypted form.

A confidant of the emigrants and a regular at the Odeon was Dr. Emil Oprecht, a publisher and bookseller on Rämistrasse. who helped many writers by printing and selling their work.

In 1915, a group of young bohemians confused waiters and guests with their strange discussions.

The sculptor and poet Hans Arp with his girlfriend, the dancer and arts and crafts teacher Sophie Täuben, the writer Tristan Tzara, the actor and playwright Hugo Ball with his girlfriend Emmie Hennings, the poet and painter Richard Huelsenbeck and the sculptor Marcel Janco set up their quarters at Odeon – thus conferring to the Café its long-lasting reputation for being a birthplace of Dadaism.

Above: First edition, Dada, by Tristan Tzara, Zürich, 1917

In their theses and slogans, the Dadaists protested not only against the war, but also against all well-established civil convictions.

Amongst the famous musicians who were regular visitors of the Odeon, we have to mention Wilhelm Furtwängler, Franz Lehar, Arturo Toscanini and Alban Berg.

Even scientists like Albert Einstein, who enjoyed discussing here physics with students from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, was one of the regulars.

Above: Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955)

Benito Mussolini, then still a fiery anarchist, and Lenin, fully devoted to reading all the available newspapers, as well as Trotsky, are just a few representatives of the politicians who came in and out.

Another long time regular guest was Ferdinand Sauerbruch, director of the surgical clinic of the Cantonal Hospital.

Because of his astonishing consumption of champagne, he offended some Zurich citizens as every day after work, he ordered and emptied a bottle.

Supposedly, he renounced this habit under the pressure of public opinion.

In fact, he had merely become more diplomatic:

The giant coffee pot from which waiter Mateo, with a wink, poured something liquid did not contain steaming coffee but… sparkling champagne.

In the years leading up to the First World War you could sit here all night, curfew being an unknown word.

The newspaper shelves were filled with international titles still leaving enough room for an encyclopaedia and a can of gasoline to fill up the lighters.

Thick smoke haze was a norm in real Viennese cafés just as were experienced waiters and various games.

At the Odeon, chess was always paramount and every Friday, Colonel Wille, later an army General, would walk in to join to a small group of cards players.

I continued my wandering through Zürich to the Cabaret Voltaire.

Above: Plaque on facade of Cabaret Voltaire, the birthplace of Dadaism, founded 5 February 1916

Hans Arp, Sophie Täuben, Tristan Tzara, Hugo Ball, Emmie Hennings, Richard Huelsenbeck, Marcel Janco and Hans Richter began staging Dada art performances at the Cabaret Voltaire at Spiegelgasse 1, where according to Janco the belief was that….

Above: Hugo Ball, Cabaret Voltaire performance, 1916

“Everything had to be demolished. We would begin again after the tabula rasa. At the Cabaret Voltaire we began by shocking common sense, public opinion, education, institutions, museums, good taste, in short, the whole prevailing order.”

Above: The Janco Dada Museum, Ein Hod, Israel

The performances, like the war they were mirroring, were often raucous and chaotic, and amongst the experimental artists on stage were the likes of Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Max Ernst.

With the end of the war, the original excitement generated at Cabaret Voltaire fizzled out.

Some of the Zürich Dadaists returned home, while others continued Dadaist activities in other cities.

Their efforts eventually helped spawn new and equally controversial artistic genres, such as surrealism, social realism and pop art.

(For more on Dadaism, please see Only imbeciles and Spanish professors: Heidi and Dada and Eternal Bliss and the Edge of Madness: Gaga over Dada of this blog.)

The Cabaret Voltaire still courts controversy today, having been saved from closure in 2002 by a group of neo-Dadaists who occupied the building illegally.

Despite police eviction and an attempt by the Swiss People´s Party (SVP) to cut funding, the building still functions as an alternative arts space.

It also contains the cosy duDA bar and a well-stocked Dada giftshop.

Alongside the fireplace in the original upstairs room can be seen a small black and white picture depicting the Cabaret Voltaire in full swing, with Hugo Ball and his friends on stage….

And an enthusiastic Lenin in the audience, his arm outstretched in support.

I climbed Spiegelgasse to photograph the building where Lenin´s flat used to be, then, after lunch and some book shopping, I boarded a train.

Zürich, Switzerland, Easter Monday, 9 April 1917

Above: Zürich Hauptbahnhof

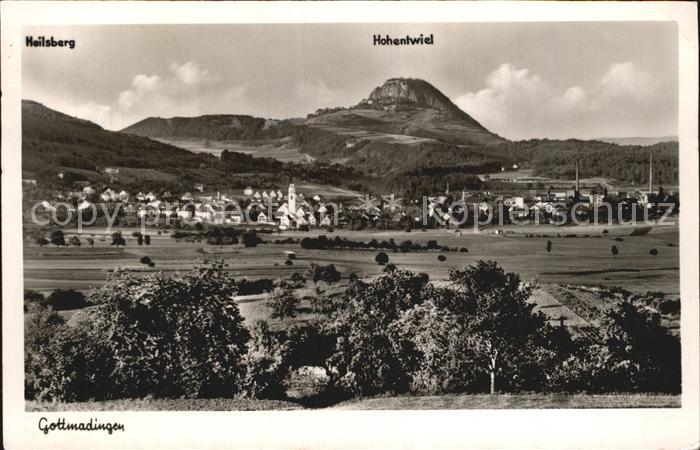

The travellers´ first train was merely a local Swiss service bound for Schaffhausen and the German border post of Gottmadingen, but the Russians approached it as if walking the plank.

Fritz Platten suggested that the travellers should imagine themselves to be like gladiators squaring up before their greatest and final contest.

Above: Fritz Platten (1883 – 1942)

This image was appropriate, for as the engine finally began to move, Lenin noticed a stranger on the train (whose presence was, in fact, legitimate, since this was not a special service, let alone a sealed carriage).

German socialist Oscar Blum had decided to take his chance and join the travellers.

Assuming him to be a spy, the Russian leader seized the uninvited intruder by the collar and physically threw him out onto the tracks.

The first two hours of the ride were almost jolly after that.

From Zürich, the local train rattled along a valley studded with the chilly stumps of vines.

Most of the passengers relaxed.

Dun-coloured farms and distant slopes had been home territory for years.

As the train slowed, just outside Neuhausen am Rheinfall, there was a momentary gasp as everyone looked to the right.

The tracks here curved beside the largest waterfall in Europe, the Rhine Falls.

(For more on the Rhine Falls, please see Chasing waterfalls and The Grand Guestbook of this blog.)

But those short minutes of romance were forgotten as the station at Neuhausen came into view, for it was one of the last stations before the German border.

A posse of Swiss customs men was waiting for the Russian group a few miles up at Schaffhausen.

The Germans might have promised a free passage for this foreign exile band, but now the Swiss were making clear that they had never signed up for the deal.

Zürich, Switzerland, 11 September 2017

Above: Zürich Hauptbahnhof, statue of Alfred Escher in the foreground

At 1630 hours, I boarded the Regional Express to Schaffhausen via Bülach and Neuhausen am Rheinfall.

There were distinct contrasts between Lenin´s journey to the border and my own:

Lenin was filled with impending doom, while I was resigned and determined to finally and firmly see the ghosts of that famous journey disappear from my own thoughts.

I certainly hadn´t needed permission nor did I question the legitimacy of my fellow passengers to ride the rails with me.

Where Lenin had seen fields and orchards in spring blossom, I saw many of these same farms on the cusp of autumn harvest.

Since Lenin´s day, the largest crop production in Bülach seems to be hockey players.

Above: Bülach Railway Station

I already knew both Bülach and Neuhausen quite well as I had walked in the past beside the Thur River from its Alpine origins to its confluence with the Rhine River near Bulach, and I had walked from my village of Landschlacht following the shores of Lake Constance to Konstanz and the Rhine River to Schaffhausen and its junction with the Thur.

So I no longer gasp with astonishment when I see the Rhine Falls, though they still thrill me with their majesty every time I see them.

Above: The Rhine Falls

Schaffhausen, Switzerland, Easter Monday, 9 April 1917

Lenin´s group were escorted from the train.

As they waited on Platform 3, officials of the Swiss police rummaged through the group´s baskets of blankets, books and provisions that they had brought for the journey.

It turned out that there was a wartime rule about exporting food from Switzerland.

The cheese and sausage and the hard-boiled eggs were confiscated.

It was a shock to watch as an entire week´s supply of sustenance was snatched away, and the humiliating process itself (which left only a few bread rolls, precisely counted, and a stamped receipt) was enough to set anyone´s nerves on edge.

Schaffhausen, Switzerland, 11 September 2017

Above: Schaffhausen Bahnhof

The removal of the passport control signage and the use of the platform kiosk as a customs office on Platform 3 is now a relic of the past.

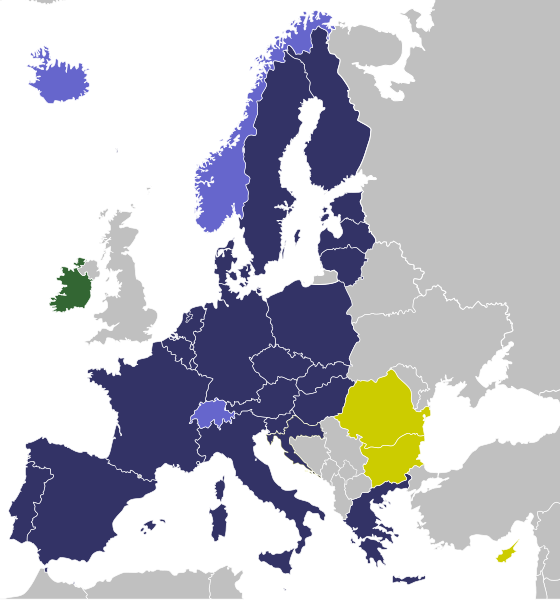

Switzerland, though independent from the European Union countries that surround it, signed the Schengen Agreement in 1985, allowing mostly unrestricted border passage from it to its neighbours.

Above: European Union members (dark blue), non-European Union members but signatories of the Agreement (light blue)

(Whether this relaxed attitude towards arrivals and departures will continue remains debateable since the 2015 migrant crisis.

For a discussion of the migrant crisis and the European borders issue, see Burkinis on the beach, Behind the veil: Islam(ophobia) for dummies, and Fear Itself of this blog.)

(Interestingly, the restrictions on food are now on food coming into Switzerland rather than leaving it.

Switzerland wants to encourage the Swiss to do their grocery shopping at home, but considering that shopping over the borders is substantially cheaper, this is a difficult argument for the Swiss government with which to convince the Swiss.)

I took a few photos of what remained on Platform 3, grabbed a coffee at the Station and boarded the 1739 train to Thayngen.

Thayngen, Switzerland, Easter Monday, 9 April 1917

At Thayngen, not far up the line from Schaffhausen, a fresh squad of uniformed men demanded the Russians to go through all their possessions again, for this was the very last station before the German border.

Thayngen, Switzerland, 11 September 2017

Above: Thayngen Railway Station

I had never been in Thayngen before.

Prior to my reading of Catherine Merridale´s fine history, Lenin on the Train, I had never even heard (nor cared) about this village of nearly 5,000.

This village in Canton Schaffhausen is merged with the villages of Altdorf, Bibern, Hofen, and Opfertshofen to form the municipality of Thayngen.

This is a working man´s village, with an unemployment rate of only 1%, though more people work outside the municipality than within it.

Here the hungry traveller can eat at one of the nine restaurants.

Here the weary wanderer can sleep in one of the 31 beds in one of the three hotels.

The village itself is not that particularly fascinating to the international cosmopolitan jetsetter, possessing only two sites of national significance: the Haus zum Hirzen and the Haus zum Rebstock.

Above: Thayngen town centre

The explorer must leave the village and visit the nearby prehistoric cave dwelling at the Kesslerloch or the Stone Age riverbank settlement called the Weier.

Above: Prehistoric cave dwelling, Kesserloch

The most common site the visitor sees in Thayngen are trucks passing from Germany into Switzerland.

Historically, only three Thayngen personalities leap off the pages of time to grab one´s attention: Hans Stokar (1490 – 1556), a businessman, politician, historian, church reformer and pilgrim to both Santiago de Compostela and Jerusalem; Martin Stamm (1847 – 1918), a pioneer in American surgery; and Everard im Thurn (1852 – 1932), the son of a Thayngen banker, who became an author, explorer, botanist, photographer, and the Governor of Fiji (1904 – 1910).

The weather this day was as problematic and uncertain as my Lenin-following excursion was: dark clouds wrestling to cover the optimistic sun.

But the result was a beautiful rainbow across the sky above the village.

Here, close to the station that aggravated Lenin´s travelling party, I came across an outlet shop of the company Unilever.

Unilever, a British-Dutch company with headquarters in Rotterdam, a manufacturer of food and beverages, cleaning agents and personal care products, is both the world´s largest consumer goods company and the world´s largest producer of food spreads.

Europe´s 7th most valuable company and one of the world´s oldest multinational companies, Unilever has made its products available in over 190 countries, offering over 400 brands, including Axe, Lynx, Dove, Becel, Flora, Hellmann´s, Knorr, Lipton and Rama, just to name a few.

Unilever was founded in 1930 by the merger of the Dutch margarine producer Margarine Unie and the British soapmaker Lever Brothers and has, over time, made many acquisitions, including Lipton and Ben & Jerry´s.

I happily bought a number of items at the outlet price, not knowing that Unilever has been criticised by Greenpeace for causing deforestation, by Amnesty International for child labour and enforced labour practices, by Israel for salmonella in cereals, and by the Indian town of Kodaikanal for dumping mercury.

Most consumers, myself included, rarely think about the business practices of the companies who produce what we buy.

After filling my backpack with Unilever booty and wandering around Thayngen a bit, I then boarded the 1820 train to Gottmadingen.

Gottmadingen, Germany, Easter Monday, 9 April 1917

When the Swiss train came to its final stop at Gottmadingen, the Bolshevik passengers were close to panic.

To their despair, as they scanned the platform outside, they spotted two unsmiling figures in grey uniform, the hard-faced types that people send when they are planning a surprise arrest.

These German officers were hand-picked men.

Lieutenant von Bühring was the younger of the two, his superior being Captain von der Platz.

The travellers were not to be informed, but Bühring had been selected for the job because he understood Russian.

The officers had both been briefed for the mission by the director of German military operations, General Erich Ludendorff, in person.

After the sterile bureaucrats of Switzerland, Bühring and Platz made a terrifying pair, all gleaming boots and razor-sharp salutes.

They ordered the Russians to form two lines inside the third-class waiting room, the men on one side and the women and children on the other.

Instinctively, the men surrounded Lenin.

Several minutes passed, and although no one dared to speak, most wondered privately how they had fallen for this German trap.

The pause gave the Germans time to count their guests, to watch them and to organise their baggage.

It was a calculated move to show the Russians who was boss.

When the officers were satisfied, they ushered their party from the station building without volunteering an explanation.

Outside, the engine awaited, already spewing out white steam.

Berlin had honoured its agreement to the letter.

This was a journey that cost much, in resources and precious time on railway tracks.

The single wooden carriage, painted green, consisted of three second-class compartments and five third-class ones, two toilets and a baggage room for the émigrés´ baskets.

This was to be the famous sealed train, though what the security amounted to was merely that three of the four doors on the platform side were locked after the passengers had all been counted on board.

There was an awkward moment as the Russians debated who might sit where.

After a token protest, Lenin and his wife agreed to take the first of the three second-class compartments at the front.

The other two were offered to families with women and children.

The rest took their places in third class, resigned to stiff limbs and drowsiness.

The German guards sat at the back.

To preserve the illusion that the Russians would have no contact with the enemy, a chalk line had been drawn on the carriage floor between their territory and the rest.

The only person who could cross it was the Swiss socialist Fritz Platten, who had become the entire company´s official middleman.

As the train slowly headed north, Lenin stood at his dark window, a modest figure in a dusty suit, thumbs locked into his waistcoat pockets.

Beyond his own reflection in the glass, he could see that the alder woods were turning green.

Despite the lengthening shadows, it was still possible to make out yellow celandines and white anemones, the first wild flowers of spring.

The valley broadened, opening to fields.

Switzerland vanished into the trail of steam, the rhythmic rattle of the train encouraging a feeling of momentum, of purpose and progress.

The mood was smoothing and hypnotic.

Gottmadingen, Germany, 11 September 2017

Above: Gottmadingen, Germany

Gottmadingen was another town I had never explored and though it is twice the size of Thayngen, I found it half as interesting, for Gottmadingen suffers the fate of all towns too close to more populous and famous locations, it is generally ignored, as it is only 5 km southwest of Singen.

Right up to the 20th century, Gottmadingen remained a tiny village, but economic growth caused by a growing number of new factories demanding workers the village grew to become a town of over 10,000 residents.

Gottmadingen´s industry was mainly based on the production of agricultural machinery.

In the years 1960 to 1970, more than 4,000 workers were employed in the Fahr factory for agricultural engines.

The factory closed in 2003.

Though the town tries to be productive with the highrise Sudhaus, thriving business at the Hotel Sonne and regular customers at Pimp Your Hair, Gottmadingen felt sleepy and decaying.

Even though Alcan Singen, a Canadian company branch that produces aluminium automobile parts, is located in Gottmadingen, the town itself slumbers.

It has four churches, with St. Ottilia possessing Germany´s oldest church bells (1209).

There are castle ruins strewn all around, with Herlsberg and Kapf Castles behaving much like Gottmadingen itself, present but unattractive.

Randegg Chateau, built in 1214, does still stand and once was the home of painter Otto Dix and his family from 1933 to 1936, but it is now in private hands and open to the public only once every two years for an experimental art exhibition.

Above: German painter Otto Dix (1891 – 1969)

Except for the town´s Tractor Museum, there isn´t much to attract visitors outside of the cities of Schaffhausen or Singen.

While waiting for a train bound for Singen, I read of a train accident near Andermatt, the 16th anniversary discussion of the unaccounted-for victims of 9/11, Republicans accusing Democrats of wanting to remove 9/11 memorials like they wish to remove Confederate statues, and the proposed evacuation of six million residents from south Florida due to the devastation of Hurricane Irma.

There seemed to be life continuing on beyond the town limits of Gottmadingen.

Landschlacht, Switzerland, 4 November 2017

Lenin, like myself, would continue on to Singen, then we parted company.

Lenin and his band of Bolsheviks would travel through Germany via Rottweil, Horb, Tuttlingen, Herrenberg, Karlsruhe, Stuttgart, Frankfurt, Halle, Berlin and Sassnitz.

They would then take a steamer to Sweden, then another train to Malmö and Stockholm.

After a brief stopover, then yet another train to Lulea and Karungi to the Finnish frontier, then Russian territory, at Tornio.

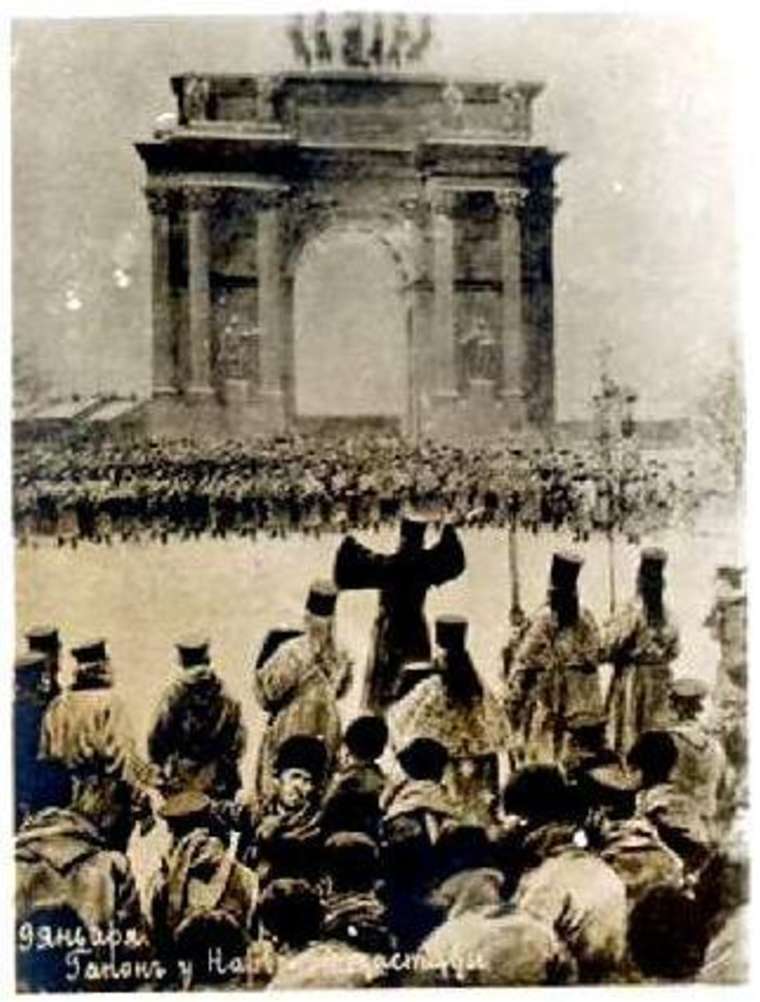

Then finally arriving at Finland Station in north Petrograd, today´s St. Petersburg.

A few months fraught with uncertainty would follow, but then in October 1917, Lenin and the Bolsheviks would seize control of Russia from the Provisional Government, in a coup d´ état that would later be called the October or Bolshevik Revolution.

Lenin today remains something of a contested figure in world history.

This is a great injustice for all those he would go on to murder and terrorise.

He would be directly responsible for the deaths of 300,000 people at the hands of his secret police.

A famous quote of his: “A revolution without firing squads is meaningless.”

He gave the order for the execution of Tsar Nicholas II and his entire Romanov family.

According to Simon Montefiore, an authority on Russian history, Lenin was the man “who created the blood-soaked Soviet experiment that was based from the very start on random killing and flint-hearted repression, and which led to the murders of many millions of innocent people“.

Lenin “relished the use of terror and bloodletting and was as frenziedly brutal as he was intelligent and cultured.”

Germany wanted the Russians out of World War I, and by sending Lenin to Russia, this is precisely what they would achieve.

But by doing so, they carried across their borders a true monster of historic proportions.

Switzerland was truly well-rid of Lenin.

By retracing his steps, so was I.

I continued onwards from Singen to Konstanz, back across the Swiss border to Kreuzlingen, and from there back home in Landschlacht.

Evil prospers when good men say nothing.

Evil re-emerges if history is not remembered.

Sources: Wikipedia / Google / Duncan J.D. Smith, Only in Zürich: A Guide to Unique Locations, Hidden Corners and Unusual Objects / Tony Brenton, (editor), Historically Inevitable?: Turning Points of the Russian Revolution / Catherine Merridale, Lenin on the Train / Simon Sebag Montefiore, Titans of History / Robert Service, Lenin: A Biography / Alexander Parker & Tim Richman, 50 People Who Messed Up the World / Café Odeon Website